[dropcap]S[/dropcap]ophomore Sana Khader was raised with values that signify an acute respect for the ability to grow up in this country. For as long as she can remember, her parents have been amplifying the ideal that they must be grateful each every day for the opportunities given to them in the United States.

“My dad is really proud to live here and really thankful for that,” Sana said. “It helps to have your parents impose that attitude.”

Sana’s parents were both born and raised in India and have brought up Sana and her sister under the Islamic faith. While Sana’s parents are not very religious, she has taken interest in her Muslim heritage and in the ideals of Islam as well.

Sana’s father went to college in the United States and both of her parents learned English in school as children, Sana and her sister are the first in the family to grow up in the United States.

She has traveled to India numerous times and her family traditions have instilled within her a great hold onto her cultural footing. She is very aware of the differences between both cultures, and she has always enjoyed being able to compare the dynamics.

“In India, there is no such thing as a teenager just going into their room and shutting the door and doing their own thing,” Sana said. “One time, we went to India and were staying there for six weeks, and I had a book and I went into a room and was reading it for a couple of hours. My mom said, ‘You should come out. That’s not how it is here.’”

Aside from seeing the differentiation between the societal norms, she has also sensed real problems with India’s gender imbalance. Having been born and raised within the liberalism of California, it is a stark contrast to have learn and see, through communication with other Hindi and Muslim friends, that there is an injustice in the way women are treated in the Indian culture.

“I don’t experience it in my own home because I don’t have any brothers or anything,” Sana said. “But [for] a lot of my Muslim friends who do have brothers, it is an issue that their male siblings get so much more freedom.”

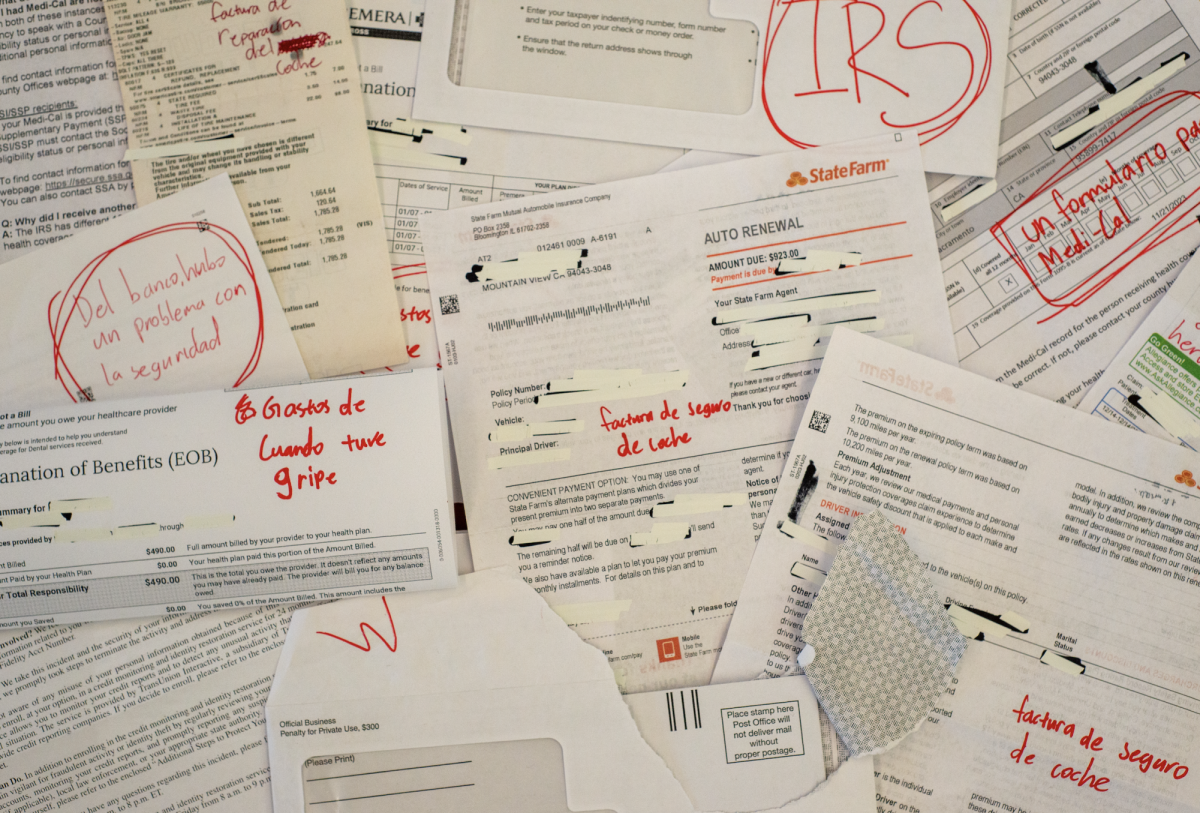

As far as linguistic differences go, Sana cannot speak the Hindi language. Being surrounded by first-generation friends who are bilingual, Sana has, for the first time, began to wish that she had in fact learned the language, as she now sees the value in it.

“I kind of feel bad because I don’t think my parents really tried to teach me how to speak Hindi when I was little. I think they would speak it to me, and I would just respond in English, so I can understand [Hindi], but in the past few years, it has totally decreased,” Sana said. “I kind of wish I had grown up speaking Hindi, just because now it seems like I want that. A couple of times I have been like ‘Dad, can you help me practice my Hindi at home?’…but then I never kept with it. It’s always a sore subject to think of.”

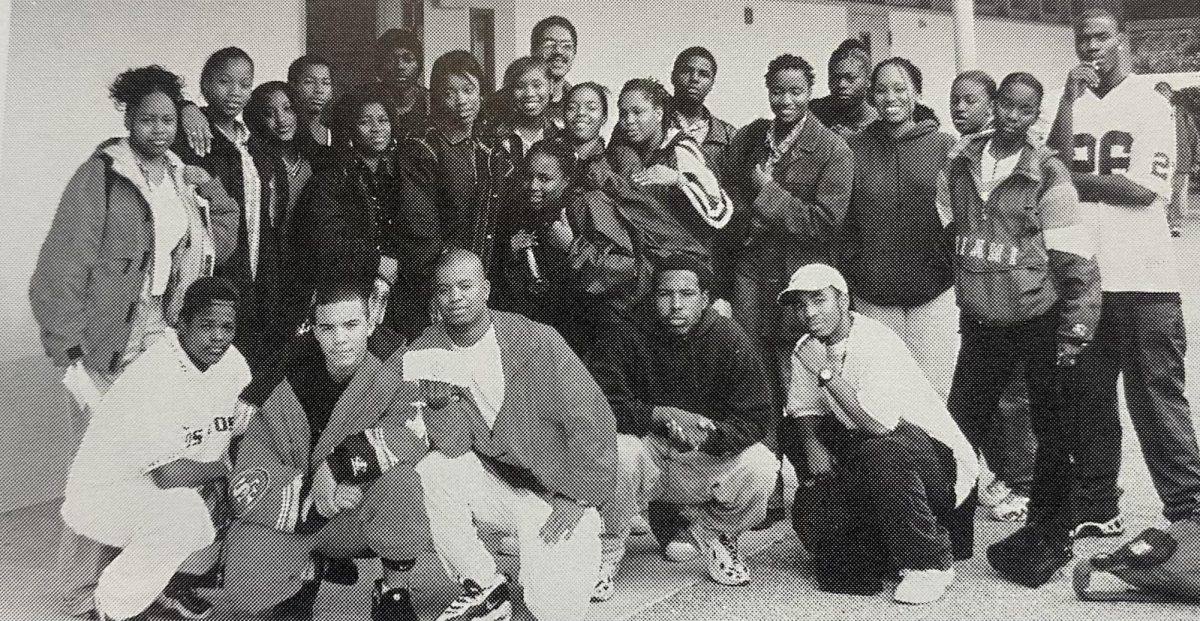

Although Sana now expresses great pride in her Hindi culture and her Muslim faith, which she believes play a huge part in who she is, this was not always the case. In middle school especially, insecurity would often cast a shadow over her confidence in the culture that she felt often separated her from her peers socially.

“In middle school, I felt like it would just be easier to be white, and I feel like middle school was very judgemental,” Sana said. “I felt like my culture and my family’s religion and cultural background was preventing me from becoming a regular American middle-schooler. And of course now, I identify with it, but back then it was really hard to fit in with everyone.”

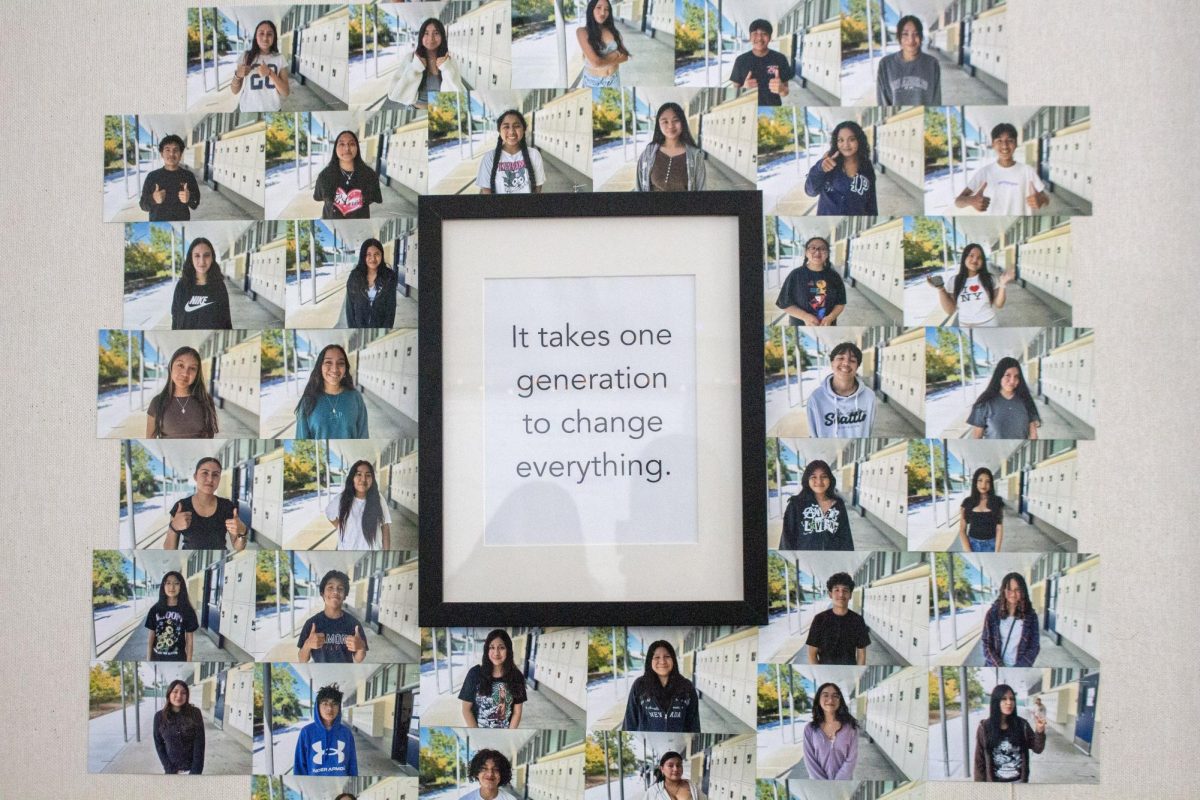

Over time, Sana has found that there are traits among her other first-generation friends, be them Indian or not, that she shares and that help her communicate with them more clearly. Simply the fact that they embrace two cultures just as she does helps them be more understanding and sensitive to the feelings she has regarding who she is as a first-generation American.

“Sometimes it is so much easier to identify with other first-generation [kids] and my other Indian friends just because you understand [them],” Sana said. “Especially because our parents grew up in countries with different ideals [from those in the United States].”

Sana has experienced insecurity as a first-generation American, but now sees it as an asset that makes her more culturally aware and gives her a more diverse background which is exciting to explore. She knows how it feels to shun who she truly is because of a need to meld into the in-crowd or to fit in. However, looking back, she knows that the most important thing is to accept herself and her culture because it is such an immense portion of what makes up her identity.

“I feel like another thing about being first-generation is that you either accept it and you really want it, or you push it away and try to be like that typical American,” Sana said. “And I feel like that is kind of sad because [it means] you are losing a part of yourself.”