Turning the struggle into a nonstop hustle

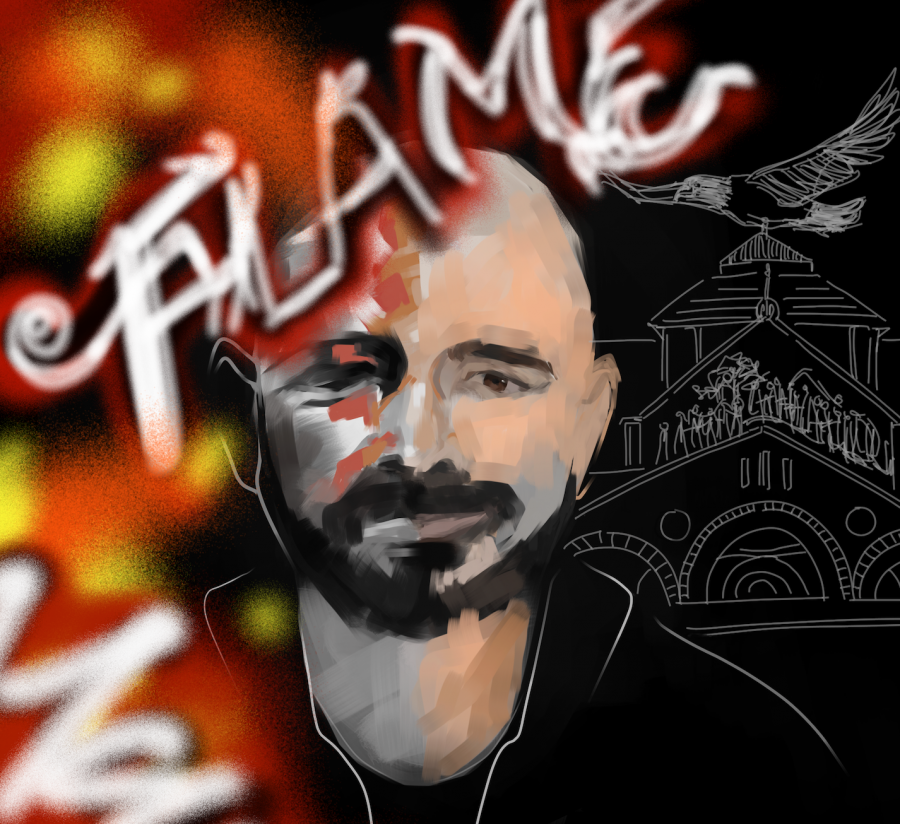

World Studies and AP Government long-term substitute David Ortiz led a far from happy childhood, born and raised in a crime-infested neighborhood with no one to rely on other than himself. Although the fallout could have echoed through to his adulthood, Ortiz made the best out of his situation, becoming a veteran, a scholar and an inspiration to everyone around him.

March 19, 2020

For most teenagers, school is a drag. We’re forced to wake up early in the morning and sometimes come back late at night.

However, World Studies and AP Government long-term substitute David Ortiz has never really stopped going to school. In fact, he’s been in school for at least 20 years—from listening to lectures to giving them. And he doesn’t plan on stopping anytime soon.

Ortiz was born to a deaf, mute single mother and raised in the Central Valley. He was raised in East Bakersfield, a crime-infested area, with his mother and grandmother, who were both not well-educated. Growing up, he had a turbulent childhood: he suffered physical abuse from his mother’s boyfriends, moved around a lot and was arrested a few times for being affiliated with gangs.

Ortiz attended a predominantly white high school where he did not have a trustworthy mentor nor adult. He was isolated due to being one of the few Latinos at his school and didn’t have any close friends. Besides that, he had to deal with blatant racism from school officials doubting his endeavors and telling him he would not be successful in life.

Determined to prove his doubters wrong, Ortiz took every AP class he could—two his sophomore year, five his junior year and four his senior year—and succeeded in all of them. Even when Ortiz became homeless due to friction in his family, his academics were above par, and he passed all of his AP Exams.

Ortiz describes his motivation to succeed against his personal obstacles as anger. The anger behind the stereotypes and labels people gave him enabled Ortiz to work harder than most in school.

“I just wanted to prove people wrong,” Ortiz said. “I had a chip on my shoulder most of the time. I hate when people look down on me and assume the worst. They assume that I’m not capable.”

No one in high school had ever approached Ortiz about college; his teachers were unsupportive and recommended that he attend community college or a Cal State, however Ortiz only had one school in mind—University of Southern California. But people doubted he could make it because of his race and low socioeconomic status.

“Sometimes it’s fueled by sympathy because people feel sorry for you,” Ortiz said. “But I’d rather have empathy than sympathy. Sympathy, in my opinion, enables people to fail. It’s all right to feel for people, but it’s not alright to allow them to fail because you feel bad for them. The standard should never be dropped.”

And frankly, the standard Ortiz had for himself never dropped. He attended USC on a full-ride scholarship where his world changed forever. The transition in the academic atmosphere from a high school to a collegiate classroom fascinated Ortiz. He was treated as an adult and enjoyed being educated in a more mature setting.

Ortiz met and connected with people who were all educated and driven like he was. But intellectual vitality wasn’t the only thing they had in common. At USC, he was shocked to see and interact with such a diverse campus, something he could never imagine after attending a predominantly white high school.

“It just blew my mind that there were men and women who were super educated and of color,” Ortiz said. “At USC, it was so easy to blend in because so many people are like you. For the first time, I met African American scholars that were from historically black colleges and universities. That was such a crazy change of mindset because I was more inclined to listen to them. I was amazed at how articulate, intelligent and thoughtful they are.”

After he graduated from USC, Ortiz joined the army. His friends in college were from the military and Ortiz had relatives serve in the Marines, National Guard and the Navy, but that wasn’t the only reason he joined.

Ortiz’s uncle, a veteran who Ortiz described as the hero of the family, would save him and his mother from any trouble they were in. After Ortiz and his mother moved away from his uncle, Ortiz couldn’t help his mother the same way his uncle could.

“True courage is to be able to see something and to react and help people,” Ortiz said. “The military gave me that. It gave me the ability to act if I saw something wrong. I wanted that same courage and brotherhood my uncle had. He went to Vietnam, and I’ve never seen him afraid of anything.”

Ortiz’s military experience has not only helped him gain the same courage his uncle had, but he had also gained a different perspective on life after he completed his service.

“It’s an eye opening experience to visit another country and see how their citizens live,” he explained. “You start to appreciate so much and so many more things. Appreciate every day as if it’s your last.” Cliches no longer become cliches, they become reality.”

On the back wall of his classroom hangs the same American flag he took with him to Afghanistan, signaling he still carries those life lessons he learned in the military with him.

After Ortiz left the military, he moved to San Diego and began teaching at San Diego High School for a few years while gaining his Master’s in Education online from USC. After spending much of his life in school, it’s no surprise that Ortiz would pursue a career in education. He eventually moved up north to obtain his PhD in Education at Stanford University and is currently studying at Stanford along with his job as a long-term substitute at Los Altos.

Before considering full-time teaching positions, Ortiz began working as a substitute teacher to observe different school districts in the Bay Area. This is not Ortiz’s first time in the MVLA school district; the year before, Ortiz was at Mountain View High School as a long-term substitute as well.

“I like this school district,” Ortiz said. “It has a unique hiring process that I like, where it involves students and I’ve already applied here. I like education and teaching because this is not a stressful job, this is a great job. Everyday here is a vacation for me.”

Despite having achieved so much in his lifetime and achieving the exact opposite of what his high school teachers expected him to be, Ortiz has never really escaped the stereotypes and labels. He’s explained that his physical appearance: bald head, tattoos and a goatee, is only him on the surface. There is more to him than meets the eye.

“I see everything as an opportunity to break a stereotype,” Ortiz said. “That’s the way I look at things. Cop pulls me over, I don’t get mad at him. Now I can sit there, show my IDs and show him I’m a veteran and a former student at this school. I’m highly educated. I’m a scholar. I’m not what you think I am.”