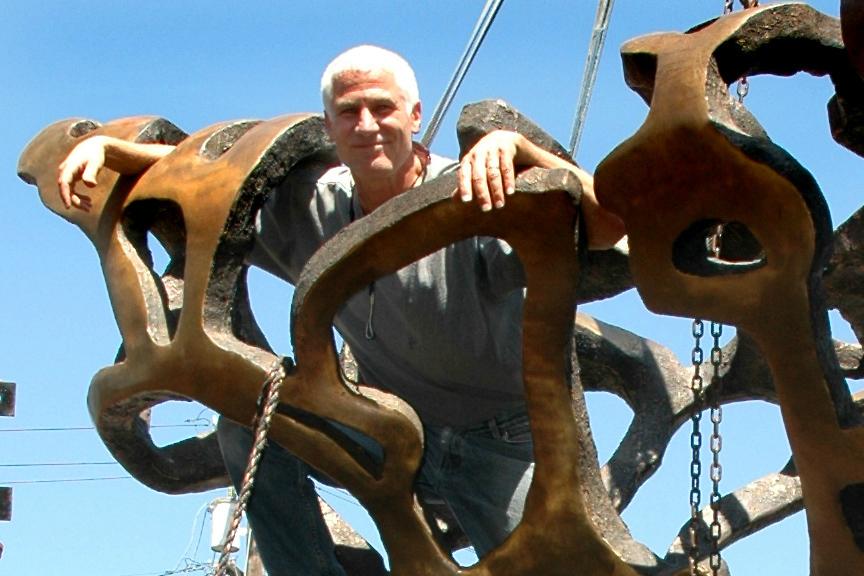

STEM Speaker Roger Stoller Molds his Career

Roger Stoller has always been fascinated by the principles that shape the natural world. When Stoller was younger, he would often picks up crab shells on the beach, observing their physical qualities and how they were created. Starting out as an industrial designer in the early ’80s, Stoller is now a master sculptor based in Silicon Valley. To this day, he still loves to examine crab shells on the beach and draw artistic inspiration from the peculiarities of the natural world.

In his early twenties, Stoller traveled around the world with renowned inventor and architect Buckminster Fuller. Fuller was most known for novel architectural designs such as the geodesic dome, and his works continue to influence Stoller today. Sculptor Isamu Noguchi also acted as a mentor, introducing him to the intersection between art and engineering, the combination of abstract ideas and concrete, physical geometry.

“I worked together with [Noguchi] since Bucky and him were friends,” Stoller said. “I got to hang around Noguchi’s sculptures, and that left an indelible mark on my soul. When I was young, I felt like I didn’t have anything to say… [But] it turns out I did have a vision, I just didn’t know I had it in that time I was doing [industrial] design.”

Throughout his fifteen-year career as an industrial designer, Stoller realized the many limitations of the corporate world and how much it differed in terms of creative freedom from the work he did with Fuller and Noguchi.

“I was in a place with my partners in my industrial design business where it just didn’t feel like the right place for me anymore,” Stoller said. “I was doing injection molded products that were going to soon end up in landfills.”

Stoller did quite a bit of soul-searching, eventually finding his internal clarity to become a sculptor. Soon after, he sold his company shares and founded Stoller Studio.

“Being an industrial designer turned out to be a good background for that, which I actually didn’t know at the time,” Stoller said. “The changes I made were more based on what was going on inside of me personally than any kind of cognitive decision to try to make money as an artist, which would not have been a very good idea.”

Stoller claims that when he was in the corporate design industry, he was considered an artist in the engineering world. Now, he claims to be an engineer in the art world. Stoller attempts to mimic natural phenomena through the physical components of his creations. His work combines traditional concepts with modern technology such as 3D printing and waterjet cutting.

“It blows my mind, what is going on around us in the physical universe and what seems to be permeating that physicality are these principles and codes, like a seed will have the code of a tree,” Stoller said. “If I could [create] anything close to a tree, I would be thrilled. There are these certain ways that nature goes about things, so I’m fascinated in that and directly applying this to my art… [When I’m] working in this very physical domain of 3,000 pound sculptures, I ask, ‘Well, how do I hold that up?’ You have got to back that up with some serious engineering and an understanding of how technology works to build it.”

Some of Stoller’s earlier works were especially complex and abstract: they were meant to satisfy himself. Over time, the essence of his creations became more focused on reaching out to the community. The 15-foot giraffe sculpture that will be revealed this month at the El Paso Zoo is a testament to the evolution in Stoller’s artistic style and medium.

“I worked together [with the zoo and the public] without any idea of what exactly it would be,” Stoller said. “It ended up being a 15-foot-tall giraffe’s head on the wall in this kind of lacy work that I do with eight other animals from Africa sort of hidden inside the lacework. It gives a unique experience for the public who aren’t necessarily art lovers.”

Stoller hopes that through his STEM talk, students will learn from his experiences and open their minds toward all professions.

“I want [students] to know that this is possible, and that technology can be used in a way that’s fun and exciting,” Stoller said. “And just to open the horizons for people that haven’t come across something like this before. I hope it’s inspiring to some people, [not necessarily] to do what I do. If you really believe that you can do something, then the sky’s the limit. But it really has to come from the inside: you really have to get in touch with what’s really important to you and follow that.”