School Segregation: An In Depth Investigation

February 13, 2018

If you visit any classroom at Los Altos, you probably can tell if it’s an AP or regular class by the skin color of the students. It’s representative of an achievement gap that spans across racial and income-based lines, and it’s a problem constantly fought by groups like AVID.

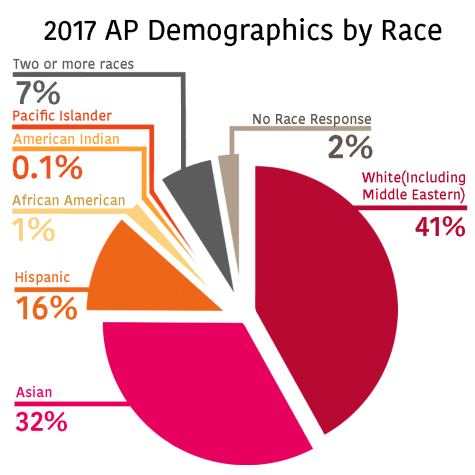

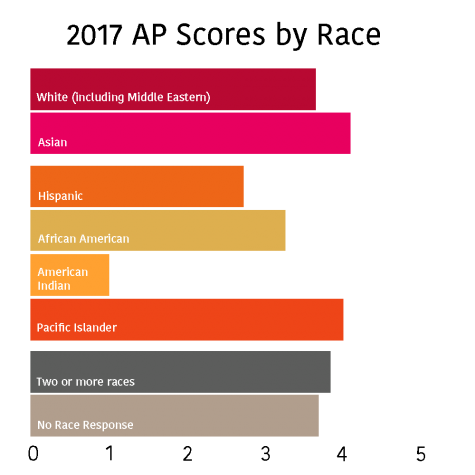

Out of the 813 Los Altos students that took AP exams last year, only 17 percent of students were from underrepresented minorities (Native American, Pacific Islander, Hispanic/Latino, Black/African American) backgrounds. Moreover, 23 percent of underrepresented students took an AP course, compared to 44 percent of white and Asian students. Because diversity has a well-documented record as an educational tool, that segregation places limits on students’ learning environments.

“Every reputable study has shown that an increase in diversity is better for all students,” math teacher Adam Anderson said. “I don’t think you get a real education in a non-diverse setting.”

But while the achievement gap is a recognized community issue, the segregated social sphere of Los Altos often goes unnoticed.

In many cases, friend groups are homogenous. Similar to the classrooms at Los Altos, there is also clear racial imbalance during lunch and brunch. Certain clubs and classes attract certain demographics because of that fact — and for the most part, the Los Altos community seems content with this reality. However, it has become clear that social segregation fosters more segregation in academics.

For many students, the friends they associate with are an important part of their choice in classes and activities. Friend groups form a big part of high school experiences and thus play an important role in the problem of school segregation. But, unlike the segregation in the classroom, students are not as worried about the segregation in friend groups.

“What’s the point of forcing people to diversify?” senior Evan Labuda said. “I mean people are happy with their friends right?”

Years of upbringing establish students’ social circles. If students go to elementary and middle schools with majority white and Asian students, their friends are likely to be of those races.

Comfort also plays a role. Students like junior Hunter Liu find that shared experiences and culture make it naturally easier to relate to certain students — students similar to himself.

“It’s so much easier to hang out with someone who could be your cousin or something, especially when you’re a kid,” Hunter said. “It lets you build better and longer-lasting relationships.”

Often, parents play a large role in the social life of their children — choosing who their kid has a playdate with, what values they instill in their children and the classes their children take.

Is this a form of school segregation? It’s difficult to find fault in students’ desire for the comfort of familiar friend groups, yet it seems problematic that students don’t believe they can build long-lasting relationships with students of different backgrounds. For many, the answer is a resounding no. After all, many students said segregated friend groups aren’t a form of explicit discrimination.

“I could understand the concern [about lack of diversity], but I personally don’t actually see it as that big of an issue,” senior Frank Zhou said. “I feel like the issue only really comes in when someone discriminates against another for not being the same race.”

Desegregation can’t be forced — it’s been tried in American history and has failed. But it’s become increasingly clear that segregation in the social sphere bleeds into segregation in academic classes. For many minority students, the lack of familiar faces in a classroom deters them from selecting a class. Without other students who relate to their experiences, they feel isolated.

“I sometimes go into my AP class overwhelmed because I look around and I don’t see anyone that looks like me,” AVID student junior Andrea Orozco said. “I know especially Latinos, they feel scared or shy to take an AP course because they feel like they aren’t good enough for it.”

Having a friend in a class can be vital for that class to be enjoyable and productive. For those braving APs and honors classes as first-generation college students, it’s often difficult to find people who can empathize with you. Lack of diversity in friend groups perpetuates a world where the path into more advanced classes for underrepresented populations is one taken alone.

“If people know that their friends, especially ones of the same race, are taking an AP class, they’ll have someone to talk to and comfortably ask for help [in the class],” AVID student senior Josh Huizar said. “Personally, the racial balance of AP classes doesn’t affect me. Most of my friends are not Latino.”

Clubs and activities also often face racial imbalance because, naturally, students join clubs that those close to them are a part of.

Without diversity in friend groups, students often aren’t exposed to different ideas or backgrounds.

As a result of never relating or empathizing with others unlike you, perpetuation of seemingly harmless jokes and stereotypes can continue, which ultimately cause lower self-esteem and more segregation.

“You hear people say all Mexicans are drug dealers and they just cause a bunch of violence, but then that Mexican person sitting next to you in class isn’t doing anything to hurt you,” junior Kiora Engelmann said. “You can’t let those generalizations get into your head.”

Stereotypes create pressure and force certain students into uncomfortable positions.

“People sometimes tell me that I’m really smart, even though I’m pretty sure they just say that because I’m Asian and ‘look’ smart,” Frank said. “It’s not as if I mind being thought of as a good student or ‘smart,’ but there’s somewhat of a subconscious effect on me where I want to meet their expectations. So, I naturally take more difficult classes.”

Educators recognize that academic and social segregation begin at the elementary and middle school level. Because of housing prices, significantly more Latino students attend K-8 school in Mountain View, and significantly more white and Asian students attend K-8 school in Los Altos. For instance, while Egan Junior High has a 9.7 percent Latino population and 46.2 percent white population, Crittenden Junior High has a 52.9 percent Latino population and 23.5 percent white population.

As a result, segregation occurs from elementary school, leading students to attain differing levels of preparation for high school.

“I went to a dominantly white elementary school, and I think that really helped me choose who my friends are still today,” senior Jennifer Miranda said. “If I had gone to another school, I wouldn’t be the same person I am today.” If social segregation widens the achievement gap, that gap’s damaging impacts only grow. Especially in English classes, different perspectives serve class conversations well. But if an AP Language and Composition course lacks minority voices, discussions around texts that deal with social commentary and critiques are limited.

“If we are reading a bunch of essays on race, but it’s a bunch of white people sitting around talking about it, that is problematic,” English teacher and AVID Coordinator Keren Dawson-Bowman said.

Even in STEM fields, diversity of perspective in the classroom and beyond is proven to provide a breeding ground for innovation. In his book, “The Difference,” University of Michigan professor Scott Page talks about how complex problems are better solved by diverse groups of people because they perceive the problem and the potential solutions in different ways. A study Page performed proved that groups of diverse problem solvers can significantly outperform high performers in STEM fields.

Beyond just improving educational experiences, it’s also a question of preparing students for the real world. Segregation in the classroom, Josh said, keeps people in bubbles where they don’t know other people’s backgrounds, leading to stereotypes.

Teachers and administration recognize this as a problem, and they’re working against the racial imbalance in classrooms. It might be constantly assigning new random seats so students must interact with more peers, like Anderson does in his class, or supporting students in taking new classes. AP Success, for instance, is an initiative designed to help underrepresented students feel more comfortable in the classroom.

Some AVID teachers, like Dawson-Bowman, host pizza lunches with AP teachers and AVID students to make students feel less intimidated. Other teachers encourage new co-workers to recognize the diversity of experiences in their classroom. The attempts have potential to bridge social and academic gaps at Los Altos, as more minority students are encouraged to brave AP and honors classrooms that can leave them socially isolated.

“The more you inquire, the more you realize how many people are coming to this campus with stories that would blow people’s minds,” English and AVID teacher Jonathan Kwan said. “How do you study for two or three AP or honors classes, maintain a 4.0, while you’re living in a one-bedroom apartment with six people, [and] there’s no quiet space?”

Alex Luna: Reader to Leader

When I was in fourth grade, I was one of the top readers in my grade. Compared to my classmates, I was reading and comprehending more books. Despite this, the teachers forced me to join a reading support group. Until this day I’ve wondered about that: why was I forced to join a class that I clearly didn’t need?

In my freshman year Biology Honors class, I was one of the only Latinos. At the time, the color of my skin wasn’t something I thought of consciously or regularly. That was until I began to struggle with cell walls and carbohydrates. I soon thought: why am I struggling when it seems like everyone else does well effortlessly? The most obvious difference was the color of their skin. I never thought about one’s color that much, mostly because in middle school everybody took the same classes so there were more people like me. There was no racial barrier between students of higher academic ability. But then, I became anxious that people like me — with my skin color — were just not meant to do well. It seemed to be the only answer I could find.

I began to notice similar trends in my other AP and honors classes as the years went on. Being one of the only minorities made me undermine my own abilities because I noticed that I struggled more compared to others. Classes became more difficult because of these anxieties caused by the racial imbalance. I will admit, my early school education wasn’t the best either. Nevertheless, this social isolation led to a decrease in my confidence and motivation to continue taking these classes.

Despite this negative mindset, I signed up for these courses because my teachers were supportive and encouraged me to challenge myself. Eventually, my anxieties faded away as I caught up to my peers through hard work. But the issue with racial imbalances in classrooms hasn’t gone away yet. Race ultimately shouldn’t be a determining factor in whether one will do well in a higher-level class. Not just in terms of students’ mindsets, but also in terms of how teachers treat racial minorities in classes.

The school needs to know how to talk about this separation of diversity while not putting a spotlight on one group, because we all know which group that tends to be. Receiving special attention may be well-intentioned, but it makes us feel that we are at a disadvantage and always will be. It sometimes feels like this spotlight means we can do nothing without the attention. We feel unwelcome and out of place.

In AVID, there are many of us that take difficult courses. What most people forget is that we are all just a regular group of students who want to challenge ourselves and use AVID as a platform to achieve the same type of success as our peers. We don’t need any special spotlight on us more than what AVID provides. That just makes it so there has to be a distinction between us and our peers.

Beyond teachers, it’s also a question of our own mindsets. Today, I am the only Latino in my AP Literature class. Does it discourage or make me feel bad about myself? No, not in the slightest. I’ve come to realize that I should be proud and not ashamed of my background. As a lower-income student, I didn’t have access to the same types of resources like tutors, making it much more difficult for me and my older sister to catch up to everyone else — especially with immigrant parents who were also trying to find their place.

One shouldn’t feel ashamed of their background, but instead use it as motivation to work harder. We shouldn’t be scared to be the only ones like us in our class.

Instead, we should realize that if we can do it, others like us can and will follow our lead. Minorities make up a large population of our school, but you wouldn’t know that if you stepped into an honors or AP course. That’s why we need to make a change.

Luckily, Los Altos has already made the first step: recognizing the problems. With programs like AP Success, there has been a genuine effort to fix this imbalance. But the issue with spotlighting persists because it puts an isolating attention on minorities.

I wish I could give a clear-cut solution, but I can’t because this problem goes beyond just the classroom. There is also an internal element to it, one that hovers over minority students because knowing they’ll have to work harder makes these courses less appealing to take. For now, to any fellow underrepresented student, don’t think you are not capable. Don’t let the color of your skin be a limiting factor. Instead, be proud of where you came from and where you can go because Los Altos is a place that can give you those opportunities.

Noah Tesfaye: Black & Booming

One of my life mentors, Stacy-Marie Ishamel, once tweeted about how you can’t be mediocre if you’re a minority in this country. That hit me hard because if anything, I want to be extraordinary — I want to change the world by helping people one life at a time. But every time I try to work hard, I end up falling under the disappointing truth of, “Black people work twice as hard to get half as much.”

Being a blip, a tiny black speck, on this diverse campus has made me want to be the best representation of people like me. I don’t ever want to give anything less than the impression that I am the most respectful, sincere and thoughtful person in the room.

I can’t afford not to give that impression. The unfortunate truth of America is that it is very difficult for a black person to thrive without taking education extremely seriously.

At Los Altos, there were 25 African American students last year in a school of over 2,000. Growing up in the Silicon Valley as often the only black or only other black student in any situation disappoints me. It’s not just that no one is there to share the experiences with you, or that you know how few black students there are at Los Altos, but it’s disappointing because I have to explain myself.

Over and over again, when I get asked, “How many APs are you taking?” the reaction to my response of “four” is one of utter shock. This kind of questioning is just a stigma of the bigger problem that I only have classes with three black kids in total and am the only black student in The Talon.

Although not spoken about, the very fact that I am the only black person in some of my classes is sad because I know there are so many capable students like me that want to achieve great things.

Everyday when I go to school, I never truly feel like I belong. Sure, I appreciate being able to say my family’s from Ethiopia, and they worked for decades to give me the opportunities I have today. But I hate feeling alone.

It’s annoying, especially when you look at the only other black person in your APUSH course and someone says something ignorant about the civil rights movement, and all you can do is shake your head. I can only hope that my presence grants someone a broader perspective. No white student can ever know the struggle it is to be a black student, dealing with overt and subtle racism on a daily basis, especially when you’re discussing an issue relating to my right to even vote in this country.

There isn’t a single day that goes by that I don’t realize how thankful I am for the opportunities I’ve been granted. But there also isn’t a day that goes by that I’m not afraid of being pulled over by a police officer; my mom sets an earlier curfew than the rest of my friends because she fears my life could be in danger if I drive at night. There isn’t a day that goes by that I don’t get almost scared looks from people when I walk downtown.

But you know what? I don’t need to give a damn about how other people perceive me. Yes, I love hip hop. Yes, I love to tackle undiscussed race issues. Yes, I only wear sweatpants or shorts and a hoodie every single day. Mr. Smith told me a few weeks ago that black students who want to achieve great things need to be okay with being uncomfortable all the time. He reminded me that even if I don’t feel like I belong, that’s the price I’m willing to pay to achieve great things.

Now, I thrive in situations that are supposed to box me in. I want to go out into this world and destroy every single preconception you have about me. Just because I’m the only black student in this lane doesn’t mean I won’t make it to the top.