Album cover of “Laurel Hell” by Mitski. Read reviews of new music from Mitski, Big Thief, yeule and Black Country, New Road.

New Album Roundup: February 2022

March 16, 2022

February 2022’s newest album releases are thoughtful and introspective, their musical medium ranging from indie folk to glitch. Here are four albums, released last month, that we think you should check out. Read reviews of new music from Mitski, Big Thief, yeule and Black Country, New Road.

Black Country, New Road: “Ants From Up There”

In Black Country, New Road’s descriptions of love, breakup and relational tension, framed through lead vocalist Issac Wood’s cryptic, metaphor-laden writing and paired with the other six members’ vast, potent instrumental soundscapes, “Ants From Up There” is a musical opus for the band, a heart-wrenching album that runs the range of the emotional spectrum in a way that few albums do.

A recurring metaphor on the album is the Concorde, the supersonic plane of yore, retired after unprofitability and a deadly crash in Paris. No commercial plane ever reached the speeds of the Concorde again. The metaphor of the plane is used to describe an infatuated relationship that falls apart with no hope of recovery (“And you, like Concorde / I came, a gentle hill racer / I was breathless upon every mountain / Just to look for your light”).

Themes of breakup and codependence permeate the album. “The Place He Inserted The Blade,” a Bob Dylan–inspired pop song that is at once delicate and energetic, describes a relationship in which the narrator depends on his partner but senses a lack of interest from them. “Good Will Hunting” describes the recognition of unrequited love (“And if we’re on a burning starship, the escape pod’s filled with your friends, your childhood film photos, there’s no room for me to go”) and the desire for connection (“I’d wait there, float with the wreckage, fashion a longsword, traverse the Milky Way, trying to get home to you”).

Just days before the release of British rock band Black Country, New Road’s sophomore album, “Ants From Up There,” Wood announced a departure from the band, citing a deterioration in mental health. Wood’s struggles set the backdrop of the album, depicting a tortured portrait of heartbreak through complex metaphors and intimate lyricism. Wood’s vulnerable songwriting and impassioned singing make every word pack a punch through all eight tracks he appears on. He could be speaking another language (he may as well be, his lyricism is often vague) and the emotion in every song would still be retained, the descriptions of emotional confusion and alienation evident.

None of this is to say that the instruments fall to the sidelines behind the vocals and lyrics — the album’s instrumentals are passionate and immaculate, powering the album as much as its singing. The music is dynamic and intricate, understated at some times and massive at others, powered by saxophone, violin and piano as well as the traditional guitar and drums. Rarely does one instrument steal the show, except on “Snow Globes,” when mercurial, hyperactive drumming entirely overtakes the song’s second half, drowning out Wood and the rest of the instruments.

The album’s full instrumental finesse is revealed on its gargantuan, three-part outro, “Basketball Shoes.” The song morphs seemingly at will, central motifs and moods changing repeatedly throughout the 12-minute song. By the end, the music is crushing, every instrument blending into one behind Wood’s tortured screams — a fittingly massive, moving closing act for an album as large.

“Ants From Up There” is a masterpiece, a near-perfect set of songs. Every song on the album is saturated with emotion and powerful instrumentals. The album is a powerful testament to relationship angst, an emotional rollercoaster that often feels just as triumphant as it does melancholic. Given Wood’s sudden departure, the album is his swan song. Despite being released just a year after their wildly different debut album, “Ants From Up There” feels like the culmination of a band fully comfortable in its sound and spells out a bright future for the nascent group.

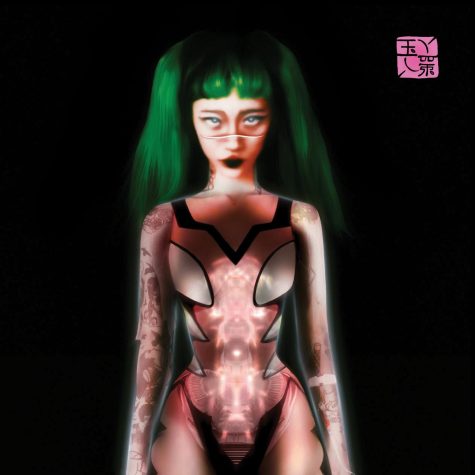

yeule: “Glitch Princess”

(CW: Themes of depression, drug abuse, suicidal thoughts/self-harm, gender dysphoria and eating disorders are described on this album.)

Glitch: the byproduct of a malfunctioning machine, the sign of a system gone wrong. Glitch has increasingly been adopted as a sonic aesthetic in a Gen Z world, the deliberate recording and replication of electronic brokenness used to wordlessly translate human angst and anxiety. This relationship is perhaps described no better than on “Glitch Princess,” the chronicled story of Nat Ćmiel, also known as yeule, and their traversal through anxiety, addiction, darkness, love and gender.

“Glitch Princess” is a delicate and distant album, its despair continuous and its hope marred. The album’s penultimate song, “Friendly Machine,” backed by pulsating synth notes, evokes the feeling of floating through a silent hellscape, a vast hopelessness, desperately searching for any escape. “Eyes,” backed by drifting piano chords and quiet yet crushing noise, features yeule’s musings on their self-perception and self-hatred (“Can you see my demons stuck to me / How can I burn out of my own real body”).

On the album’s opening track, “My Name Is Nat Ćmiel,” yeule delivers a structured autobiography, dueting with the sounds of a skipping, synthesized music box. Yeule’s voice slows, skips, stops and cuts out, barely enough to make out, and, by the end of the track, they’re engulfed by static. Their voice, struggling to be heard through a sparse musical landscape, eventually swallowed by breakdown, is an apt analogue to the backstory this album communicates.

However, this isn’t to belie the album’s moments of genuine beauty and warmth. “Don’t Be So Hard on Your Own Beauty” is a tenderly digitized, gorgeous indie-folk cut. The album’s musical despair is largely gone on this song, replaced with acoustic guitar and ethereal vocals. The song is marked by one of the album’s rare experiences of hope: the loving kind of hope so strong that it’ll stick with you through a thousand bad days. The song’s love-stricken attitude continues to the following track “Fragments,” albeit in a darker atmosphere: Between moments of sparse glitch, yeule delivers the song’s only lyrics. “I’ll tell you / With my dying breath, I love you / I’ll hold you / ’Til I stop the pain hurting you.”

The album’s outro, “Mandy,” a haunting noise piece, features yeule having a conversation with themself, chronicling the inner mental struggle of their substance abuse and depression. The album ends with the words “I can’t even trust myself, so I don’t love you anymore,” and references to “mak[ing] the pain go away” using drugs. Even though the album deals in and eventually concludes in abuse and despair, it still holds an indescribable beauty in its sound.

Big Thief: “Dragon New Warm Mountain I Believe In You”

During 2020, most of us were holed up in our homes, procrastinating on schoolwork and sleeping in — we couldn’t think of sightseeing or going outside beyond an occasional walk. Meanwhile, Big Thief was traveling the country, recording a double album across the Arizona desert, the Colorado Rockies, Californian canyons and upstate New York, each location with distinct recording styles and sonic plans. The goal was to “[encapsulate] the many different aspects of [frontwoman Adrianne Lenker’s] songwriting and the band onto a single record,” according to a band press release. The end result is an immense 20-track, 80-minute set of songs — a comforting, intimate, beautiful indie folk album that feels like sitting around a bonfire with your closest friends.

“Dragon New Warm Mountain I Believe In You” is an eclectic project, a vast album that dabbles in everything from indie rock to Americana and country to experimental rock. Listen to the first handful of songs, and you’ll get a good taste of the album’s diverse sound. The opening song, “Change,” is an understated, introspective folk cut, backed by softly strummed acoustic guitars that highlight Lenker’s voice. Her songwriting is thick with musings on life, death, heartbreak and change. The following “Time Escaping” eschews delicacy and takes a sharp left turn into psychedelic experimentation, following an idiosyncratic but infectious groove prepared by modified guitars and synths. “Spud Infinity” is lyrically and melodically more playful than the two previous cuts, evoking bluegrass in its fiddle-played melody and partially yodeled chorus.

However, even with the album’s unpredictability, it doesn’t feel disconnected from itself. It maintains a deeply pastoral and intimate atmosphere, held together largely by Lenker’s unique, poetic style of writing. Her existential and introspective reflections on relationships, humanity and time stay consistent, as do her soft, mature vocals, both of which compliment every instrumental they find themselves on. On the distorted, trippy “Little Things,” Lenker ponders the blinding nature of obsession with a romantic partner, and “Simulation Swarm” is about Lenker’s “misgivings about modern life,” according to an interview with Rolling Stone. The song describes Lenker’s experiences with breakup, her cult-involved childhood and her biological brother whom she has never met. Lenker’s lyrics aren’t immediately comprehensible — upon first reading, her poetry is intricate and difficult to comprehend, but the music still conveys Lenker’s experiences and emotions, in a deeper manner than her words.

Despite the album’s strengths as a whole, certain songs individually fall flat. The short “Heavy Bend,” which features a relaxed, looping, drum-heavy instrumental, feels unsubstantial in its aimless structure and indistinct vocal melody. “Wake Me Up To Drive,” a bedroom-esque indie pop tune, has an unmemorable chorus and an energetic drum pattern that clashes uncomfortably with the otherwise mellow song. Despite some individually weaker songs, the album is otherwise remarkably consistent during its insane 80 minutes of music. The songs also aren’t necessarily bad so much as slightly less interesting.

“Dragon New Warm Mountain I Believe In You” is a soothing, meditative listen, a massive set of songs that barely feels half its length. Lenker’s contemplative, complex writing style fuses a wide-ranging array of sounds, one that never gets boring or repetitive while simultaneously avoiding musical vertigo through the album’s many modulations. It feels nostalgic and timeless even upon first listen, like it’s existed since the beginning of time. “Dragon New Warm Mountain I Believe In You” has the power to transport its listener to deserts, to mountains, to valleys and into the depths of the human psyche.

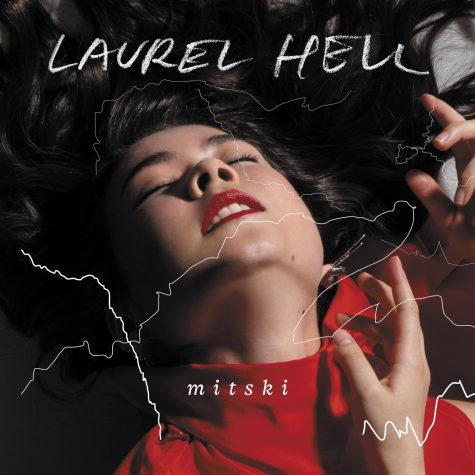

Mitski: “Laurel Hell”

In 2019, Mitski announced that she was taking an indefinite hiatus from music. The indie rock superstar, who skyrocketed to fame following a string of intimate, vulnerable and increasingly successful albums, felt increasingly detached from her increasingly public persona.

“At the end of the day, I’m a woman in public, allowing myself to be consumed,” Mitski said in a recent interview with The Guardian. “I put out songs, but really what people are buying is the product that is me.”

Mitski’s newest album, “Laurel Hell,” is said to be the result of a contractual obligation to release one more album for her record label. However, Mitski didn’t turn in 30 minutes of derivative filler and retire immediately — “Laurel Hell” is accompanied by a world tour, a full marketing cycle and a new sound. Mitski’s past flirtations with rock on albums like “Bury Me At Makeout Creek” are gone, eschewed for atmospheric synths and programmed percussion.

Lead single “Working For The Knife” foregoes a chorus in favor of a linear series of verses describing Mitski’s experience with adulthood, fame and the cruelty of the music industry (“I always thought the choice was mine / And I was right, but I just chose wrong / I start the day lying and end with the truth / That I’m dying for the knife”). Dark, humming synths, discordant pianos and Mitski’s vocals mesh into a straightforward, eerie track that pairs perfectly with Mitski’s disillusioned lyrics. Despite its relative lack of structure, it still manages to feel gratifying.

Much of the album draws from a similarly droning sound as “Working For The Knife” — the album opener, “Valentine, Texas,” contrasts Mitski’s haunting voice with minimal notes that swell into a cathartic wall of synths in the second half. “There’s Nothing Left For You” expands from a dark, repetitive instrumental into a shoegazing, noisy climax, drowning out Mitski’s voice. The album’s more quiet songs gain their power from their atmosphere, but many are lacking in structure. “Everyone,” a song similar to the first half of “Valentine, Texas” but extended to four minutes, feels inconclusive and uninteresting, despite Mitski’s superb songwriting. Similarly, the dreamy “I Guess” has a beautiful atmosphere, but doesn’t go anywhere melodically.

The album also spends time exhibiting a catchier, more melodic, more pop-oriented style. Songs like “Love Me More” and “The Only Heartbreaker” evoke classic ’80s synthpop with colossal hooks and background. These songs are written in a way unique to Mitski’s sound while still retaining her characteristically introspective and anxious lyrics. “Stay Soft,” a song about the balancing act of vulnerability, features massive piano chords and a distinctive pop structure, demonstrating Mitski’s skills as a lyricist while fitting them into a catchier sound. Mitski’s clear vocals slot into these tracks perfectly, creating some of the album’s most memorable songs.

“Laurel Hell”, potentially Mitski’s last album, is simultaneously a stylistic switch-up and an ode to what made her such a great artist. Nocturnal, minimalist styles interplay with catchy pop tunes on the project, an unexpected lattice of sounds that, for the most part, goes over very well. However, the entire album isn’t a switch-up. Her distinctively pensive writing style isn’t lost in this album’s more electronic soundstage, and it’s still her music’s greatest advantage. Even if Mitski’s music might ultimately be a product, borne of commercial obligations, her character still shines through on “Laurel Hell” as strongly as ever.