Investigating the STEM Gender Gap

Senior Zosia Stafford works on a problem in Aerospace Engineering. Zosia credits her female STEM teachers for inspiring her to continue pursuing STEM, and hopes to inspire students too. Talon file photo.

February 13, 2018

Only 10 out of this year’s AP Physics C’s 57 students are girls. In AP Biology, meanwhile, 75 out of 122 students are girls. These statistics are emblematic of larger trends, where girls are pushed toward softer sciences like biology and away from subjects like advanced physics, computer science and consequently, high level classes in fields that are still heavily male-dominated.

For many STEM teachers and students interviewed, cultural and social circumstances seem to be the root cause of this imbalance. Physical sciences are characterized as more withdrawn, solitary, “cubicle” work. Biological sciences, on the other hand, are seen as more accessible and collaborative and thus more suitable for young girls who were raised to be more accommodating and sociable. Although students may not even be aware that they perpetuate patriarchal norms or that inequities still exist, others point out problems in the classroom.

“[Sometimes], even though I have the right answer, people will second-guess my judgement, second guess my input and seek an outside third party that may not even be qualified enough to make that decision,” engineering student sophomore Michelle Parsons said. “Obviously [that] offends me and insults my intelligence and my capabilities, and that’s something that happens on the regular.”

Many of the young women interviewed expressed similar sentiments, as though they were being underestimated and undervalued, with their work, intelligence and passion not being taken seriously. But all stated they had never considered quitting for this reason. If anything, it pushed them more to continue to work for what they love.

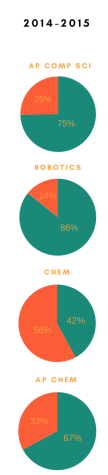

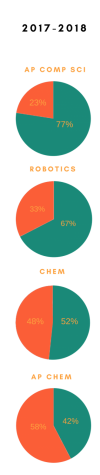

Despite this, some classes are becoming significantly more gender-balanced amongst the increase in media attention and societal discussion about gender equity in STEM. Three school years ago, the proportion of females in chemistry courses were 58 percent female in regular classes, 33 percent in honors and 33 percent in AP, according to data from the administration. In chemistry courses this school year, regular classes are 48 percent female, honors 49 percent and AP 57 percent.

On the other hand, electives remain unbalanced. In the past three years, the percentage of females in Introduction to Engineering only increased from 14 to 22 percent. AP Computer Science maintained the same imbalance with only a 2 percent decrease, from 25 percent three years ago to 23 percent this year.

A potential explanation for the difference between fundamental and applied STEM classes may be a lack of exposure, biology teacher Meghan Straz said. Straz, who also advises the Women in STEM (WiSTEM) club, said that because subjects like computer science and physics are primarily introduced in high school and more male-dominated, some girls may feel discouraged from pursuing such subjects and find it easier to join softer classes they’re more familiar with.

Yet there is a burgeoning community of young women rising to the challenge presented to them, determined to break through stereotypes. WiSTEM club member senior Zosia Stafford, who spoke at Eighth Grade Parent Night and went to Egan to speak to students about the engineering program at Los Altos, said she aimed to show how much she’s grown and prospered pursuing STEM.

“A lot of kids, specifically female students, know they are interested in science, but a lot of them are afraid they would do poorly, so I think to see someone who has enjoyed it and who has had a really good experience means a lot,” Zosia said. “I hope I’ve [raised] awareness of the programs Los Altos offers, and I hope we can start more of a trend of girls getting into the subject.”

Robotics team members sophomores Alice Kutsyy and Michelle Zhu hope to increase gender balance in the team by recruiting more female members — in fact, of the nine team members who attended the last competition in October, five were girls.

Along with female students, female teachers are also paving the way. In all STEM classes, more teachers are encouraging students to pursue their passions and break through stereotypes. Chemistry teacher Trina Mattson recalled how growing up, the disparity between men and women never discouraged her from her passion. Instead, it motivated her to persevere and bridge the gap for young girls.

“I felt that it was a shame there weren’t more women interested in [STEM] classes,” Mattson said. “STEM is a wonderful field [where] the more equal representation we have, the more we will accomplish.”

Similarly, both robotics co-adviser Karen Davis and engineering teacher Teresa Dunlap saw a significant decrease in the number of women within their higher level math courses as they pursued their STEM careers, becoming one of only a few girls in their classes. But Dunlap and Davis had fathers who were engineers and who encouraged them to go after their interests, and now hope to inspire their students too.

“Nearly all of my science teachers have been women, and I think that made a big difference,” Zosia said. “They were always incredibly supportive and helped create a fair environment in the class. I think the fact that I’ve had so many amazing women teachers has really influenced me and made me feel confident that I can succeed in such a male-dominated field as engineering.”