There’s a difference between underachieving and unable students. And a big part of that difference is a student’s own confidence in his or her learning abilities, thinks classroom volunteer Anne Battle.

“For a full year, I knew, and the students knew they were going to get an F,” Battle said, at the table with social studies teacher Christa Wemmer, talking about her experience volunteering at the school years ago. “They were left behind, and they were feeling like failures.”

Which was why three years ago, Battle and Wemmer created a team at the school to change the experience of under-performing incoming students. Now, English teachers Keren Robertson and Crystal Wright and math teachers Laraine Ignacio and Betty Yamasaki have merged their programs with Battle and Wemmer’s.

As a group, they plan a program designed to give freshmen the skills they need to succeed in high school. And now, the program graduates are finding accomplishment beyond the ninth grade.

“Most of these kids have been pretty unsuccessful thus far in school,” Robertson said. “Our goal as a team is to build the base [freshmann year].”

One of the reasons that the teachers can work together to encourage freshmen is because of a special scheduling option that allows many of the students to take these classes in double periods. Three core subjects—history, math and English—can be supplemented with a second period designed to increase in-depth understanding of that subject.

Freshman Elias Medina is involved in all three of the double-period programs, and appreciates the opportunities his double-period teachers give him.

“The best part of the classes is the extra period,” Elias said. “[And] getting extra help from the teachers.”

In Wemmer’s World Studies class, she teaches a lesson in the first period. In the second period, peer tutors work with her students on textbook reading and note-taking skills.

Though Robertson’s students are spread throughout 10 freshman Survey classes, Robertson focuses her Survey Skills class on laying writing foundations such as essay writing (with the help of peer tutors).

In Yamasaki’s math class, she spends the first period covering the state standards about algebra. In the second, peer tutors work in small groups to go over algebra concepts again. And like Battle, who is an aide to Wemmer, Lorraine Wagner assists Ignacio and Yamasaki.

The double period teachers use multiple intelligences (like visual, auditory and group learning) to find many ways to communicate skills to students.

“These are smart kids,” Robertson said. “But they may not be able to show their smarts in other classes.”

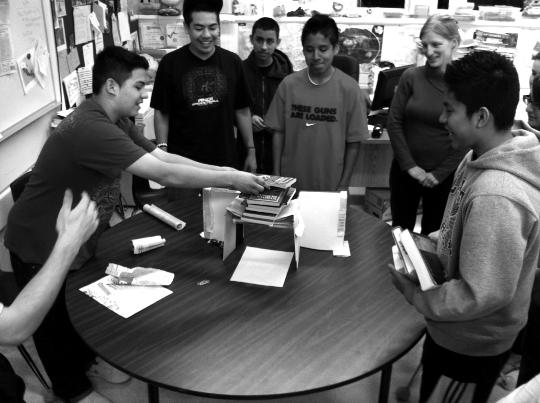

During the unit about the Industrial Revolution, Wemmer and Battle had their freshmen build bridges out of newspapers, paperclips and dictionaries (pictured above). Activities like bridge building are designed to engage students who might have a hard time imagining the impact of technological improvements during the 1800s.

Like Elias, freshman Carlos Rivera-Solis is also involved in all three of the double-period programs.

“[The teachers are] helpful, they’re respectful, they’re fun to be with and they make learning fun,” Carlos said. “[And history] class is better because we get more help with teachers and tutors, and they really understand.”

For students like Carlos, a larger lesson in one period and a focused application in the other are two opportunities to digest information. In World Studies, the focused applications are sometimes taking notes or activities that connect history to current events.

In Wemmer’s class, she shows online videos about the democracy movements in the Middle East and northern Africa to bring the revolutions to life in the textbook. In Survey Skills, Robertson shows her class example essays before freeing the students to work on their own.

“If nobody is there to break it down, [the kids] give up,” Robertson said. “And if I give them the scaffolding and skills, they can do it.”

What’s special about this team of teachers is that they don’t focus all their attention on teaching methods and curriculum. The group spends a good amount of time talking about individual students.

If one student is having a bad day in a class, the other teachers can discuss the student’s behavior in their classes and think over some possible solutions. If three of a student’s core curriculum teachers know there’s a problem, it’s much harder for that student to blend into the background.

“In class, [students can] act out or become invisible,” Robertson said. “When we can all work together and share that communication, we can be much more effective.” Battle agreed.

“With a team of teachers, no kid gets overlooked,” Battle said.

Part of Wemmer’s strategy for not letting students act out or become invisible is making sure they are self-confident. It may not be included in the course description, but she believes that routine content presentations in front of their classmates and the intimacy of peer tutor groups can give students confidence about their learning abilities.

“We are really focused on skills and literacy,” Wemmer said. “But we are also getting students to do a lot of presentations, and being comfortable with vocab and content.”

“And,” added Battle, “we want to build their self—steem.”

Each night, students in Wemmer’s World Studies write a daily journal on a topic that was taught that day in class. Though the journals are only a page long, it gives students time to free-write and find out how well they understand a topic.

“This class has helped me learn a lot more than any other classes because of daily journals and the double-period,” Carlos said.

His fellow freshman Jesus Romero thought his improvement was more due to the note-taking abilities he gained this year.

“I used to take ‘stupid’ notes,” Jesus said, and laughed. (Carlos, who is in his group during the second period, then jokingly called him stupid.) “Now I take at least three to five bullets a paragraph, even if it’s a short one.”

Many of the teachers also attend Homework Club after school, where they put in more time helping students individually.

Both Wemmer and Battle know the program still has a long way to go. They want to participate in more “interdisciplinary work,” which would mean that a unit could be applied in social studies and math classes.

At the weekly meetings, reflection and brainstorming by the cross-department team helps to “continuously improve the program,” Wemmer said. They have counseling and administrative support, and together the team formulates a plan to help students.

“We do everything we can to make a student successful,” Wemmer said. “We believe it’s our job to motivate them.”

For Robertson, the number one goal is to teach students “how to build a relationship with a teacher, and how to ask for help.” Then, it’s “read more effectively.” If a student doesn’t know how to ask a teacher for help, odds are the student won’t succeed.

“I want [my students] to learn how they can be successful the rest of their math education,” Yamasaki said. “I want them to feel and know that they can be successful by determination and focus, and like in everything else, be disciplined to learn.”

Both Wemmer’s and Robertson’s favorite part of their job is getting to connect with students, by learning about them and their families and then seeing them succeed in school after freshman year.

“This is the first time for many of them that they’re excited about history,” Battle said with a smile. “And now a lot of them say, ‘This is my favorite class.’”

For Yamasaki, it’s much of the same sentiment.

“I really enjoy helping students first see that they can do math and that they have the capability to understand the math,” Yamasaki said. “I enjoy the challenge of convincing students that algebra ‘isn’t all that hard.’”

“Hey, teacher lady,” Carlos called, referencing an inside joke between them, from when Carlos once forgot Wemmer’s name. “I finished my notes!”

Wemmer laughed.

“Great, student boy,” she said back. Then she went over to check his notes.

They never waste opportunities in the classroom to teach.