We all know what isn’t healthy, like a double cheeseburger from McDonalds (490 calories) or a medium-sized coke (65 grams of sugar), yet so many Americans still opt for unhealthy food choices.

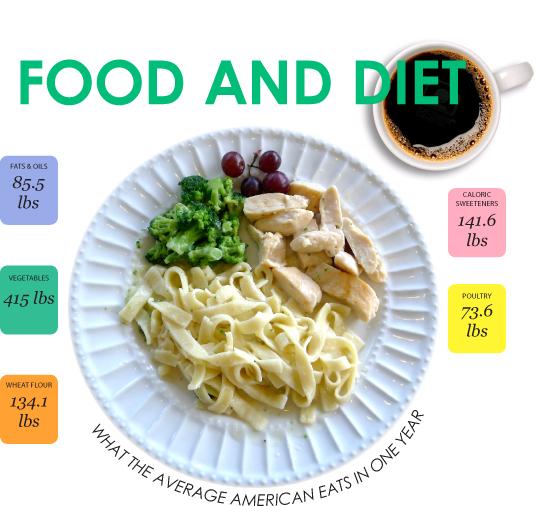

According to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, on average, males consume a total of 2,475 calories every day, while females consume 1,833 calories. Thirty-three percent of the calories consumed come from fat—high compared to the recommended 27.5 percent.

Kids from 2 to 18 years old lead lifestyles with diets that are composed of 40 percent empty calories—calories from foods without any real nutritional value.These empty calories mainly come from meal items that include soda, sugary fruit drinks, desserts and pizza.

Reward Response

Despite learning all this in Health Class, sophomore Alex Kuo still eagerly awaits his weekly pepperoni pizza order from Spot’s Pizza Place.

He immerses himself in the familiar aroma of the kitchen. To him, the pizza shop is a home of sorts. It’s where he spends a lot of his time ordering food that, while not the healthiest, is the most convenient.

If it tastes good, makes him feel good and is relatively inexpensive, it’s definitely an ace for this tennis fanatic. Moreover, savoring each slice of pizza gives him no uneasiness about his decision.

His adoration for eating out at Spot’s represents a characteristic typical of many Los Altos High students. Thirty-six percent of students (200 students polled)eat fast food at least once a week, with another 15 percent returning more than once to the local McDonalds or Jack in the Box before the school week is over.

Despite Alex being well aware of the immense amount of calories saturated in the grease and extra cheese topping, $5 for two delicious slices of pizza is too good to pass up.

However, Alex does have his gripes about eating out too often.

“Just don’t do it every day,” Alex said.

But it’s more than just convenience and price that drives Alex to come back to the same pizza parlor every week. Eating his pizza provides him some mechanism to stop contemplating, to stop worrying about other distractions at school or in life. For those 20 divine minutes, it’s just him and the pizza.

Dr. Clyde Wilson who teaches Human Nutrition at Stanford notes that this “feel good” stigma that comes from eating high-calorie foods is typical of teenagers.

Comfort foods loaded in sugars, fats and calories generate a sort of reward response in the brain by releasing chemicals such as serotonin, which is responsible for generating feelings of happiness.

“Teenagers tend to be more impulsive, meaning following their reward response, than older adults, but many older adults eat by their reward as well,” Wilson said.

Whether it’s impulsive behavior or the reward response, food entails its own living culture of what we eat, how we eat it and with whom we share it. More often than not, the health aspect of what we eat is not the most predominant factor in our choices in diet.

Sophomore Tony Tran represents the world of convenience. He’d rather kick up his legs on a couch and indulge in the world of junk food than waste precious minutes on a stove actually cooking. Food is his medium to connect with his alter-world: Call of Duty.

“I kinda don’t care about what type of food I get,” Tony said. “Food is good.”

As a football player and a track runner, he works off any of the empty calories he eats and balances out his cravings for rather unhealthy food.

That’s not to say he doesn’t desire to eat healthy. Rather, Tony’s cravings for all sorts of food leads to something that might be worse than his cravings—lethargic behavior.

“Laziness is infectious,” Tony said.

He doesn’t know whether his semi-lethargic behavior found its roots in his lazy ways of eating or rather, if his lazy eating amplified his lethargy.

All he knows is that he’s perfectly fine with it.

With a broadening grin on his face, he only has a single word to describe Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 3 with some chips and a pizza.

“Heaven.”

Preparation

While Alex and Tony devour what’s at hand with little or no question over what exactly is in what they’re eating, junior Mohan Avula takes a different approach with his food. Although his cooking has not always been and is still far from Iron Chef level, his continuous effort in improving his cooking skills has helped him develop a more intimate connection with the food he makes and eats.

“Initially when I made food, I felt even less inclined to eat it,” Mohan said. “But I’ve gotten better and now appreciate how hard it is.”

Whether it’s just preparing sandwiches for lunch or the occasional preparation for dinner, Mohan feels like his work does not go unappreciated. He eats and appreciates his food more because of considerable effort that he puts into his preparing his meals.

The process of preparing his own food puts him face to face with choosing what ingredients go into his food: brown sugar versus refined white sugar, real butter versus a substitute.

The fine details in choosing and preparing ingredients gives him more incentive to make healthier decisions than he would’ve with pre-made food.

However, not all students are given the healthier choice or can even indulge in what they eat every night. Students like junior Caroline Deng simply eat “what’s there.”

A normal school night for Caroline consists of over 30 pages of USHAP reading and another AP Language and Composition assignment.

So instinctively, she grabs a bag of potato chips and makes herself a cup of ramen noodles. She knows that these choices aren’t the best, but she can’t help herself.

The cup of ramen noodles only requires one minute in the microwave, so it seems to be the best time-saver.

“I go for really unhealthy foods when I’m stressed,” Caroline said. “I don’t have a lot of time, and I don’t want to go into the kitchen to make something with more nutritional value.”

While Alex, Tony and Caroline’s choices of food may not be the healthiest, eating alone and what’s simply there reflects 41 percent of students: 15 percent of whom never have dinner with their family and 26 percent only sometimes.

These numbers are reflective of the ever-growing trend of eating alone in American culture, which is just as unhealthy pyschologically as high-calorie content foods.

According to a decade-long study of family eating patterns published in 2005 by the National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse (CASA) at Columbia University, kids who do eat with their families every night are 40 percent more likely to maintain A’s and B’s in school than kids who don’t.

Furthermore, minimal emphasis on family dinners is also an increasingly American trend. Researches also found that foreign-born kids are more likely to eat with their parents.

Junior Margherita LaCapra comes from a household which is deeply rooted in Italian food and culture. She usually prepares her meals from scratch with her family, making rich foods with ingredients such as basil, olive oil and a variety of cheeses to make delectable pastas, lasagnas and tortellinis.

“I always have breakfast and dinner with my parents every single day,” Margherita said. “I find it really important to keep a strong relationship with my parents and having dinner together only strengthens the connection we share.”

Not only is a sense of family instilled through having family dinners, Margherita says, but they also help her make healthier eating choices.

“We never accomodate food for just one person, so we all eat the same things,” Margherita said.

Lunch Time

Whatever freedom students have at home when it comes to their meals dramatically decreases at school.

Sophomore Kelsey Kawaguchi spends five minutes every night preparing her turkey sandwich, saying the pizza from the pizza cart is “too greasy.” In addition, students like junior Steven Dittmer shy away from the cafeteria, thinking “the food is kinda gross.”

Shying away from cafeteria food, many students eat lunch outside of school at places like Chipotle or McDonald’s.

However, while food from the cafeteria may not be the best-looking to some, there are no doubts when it comes to its health and nutritional content. The school, along with all other public high schools in California, follows Senate Bill 12, which requires individually sold entrees or meals to qualify under the federal meal program, have fewer than 4 grams of fat per 100 calories and 400 total calories overall.

The Healthy Beverage Bill passed in 2007 requires fruit-based or vegetable-based drinks to contain at least 50 percent fruit juice. Milk products and an electrolyte replacement beverage must also contain fewer than 42 grams of added sweetener per 20-ounce serving.

A common hot meal sold at the cafeteria during lunch, like spaghetti with meat sauce, strictly follows these state guidelines through a specifically provided recipe. The ground beef found in the weekly spaghetti contains no more than 20 percent fat, parsley, basil or garlic. Containing minimal amounts of saturated fat and total fat, each serving is only 322 calories.

However, these strict food requirements do not affect students like junior Sean McLoughlin. He goes off campus and buys a pizza at New York Pizza every day because it is “easy to get” as he returns from Freestyle.

While not apparent, getting a $3 meal from the cafeteria is healthier than going off campus to places like McDonald’s or Chipotle.

However, regardless of personal preferences and lifestyle situations, there is no black and white in what is the correct, healthy way to eat.

“If [students] have goals that nutrition can help them with, they should engage their mind in how they are eating so that they can get what they want out of life,” Wilson said.

Going Green

The sentimental classic, “Charlotte’s Web,” by E.B. White inspired sophomore Sophia Drobny to eat organically, a lifestyle she has kept up for the past five years.

As a co-founder of the People for Animal Welfare (PAW) club, Sophia is concerned with the treatment of farm animals because of the inhumane conditions in which the animals live. She started to abstain from eating meat in protest of their conditions.

“They live in really tiny cages and they can get infections,” Sophia said. “It really disgusts me.”

Green Team Co-vice president sophomore Sarah Jacobs also feels strongly against how animals are treated in industrial farms. In fact, Sarah raises her own chickens at home. Sarah’s three chickens live in a chicken coop in place of the family’s old play structure and provide fresh eggs during the spring and summer.

Her mom really wanted to try raising chickens.

“It’s kind of like a family project,” Sarah said.

Sarah’s family has been involved in the organic and local scene for as long as she can remember. Ever since fifth grade, Sarah, a vegetarian, has focused on making her own diet fresher and more organic.

As part of their goals for a healthier diet, Sarah and her family grow several types of vegetables.

Once they grew 14 different types of tomatoes. She even wakes up at 7 a.m. to go to the Master Gardeners Tomato Sale in San Jose with her mother and younger sister to hunt for some more of their favorite tomatoes.

“It sounds like a really dorky thing to do,” Sarah said, with a laugh. “There are like 2,000 people … There are lot of crazy gardening people there.”

Science teacher Greg Stoehr is another longtime customer of the farmers’ market. During his years at UC Berkeley, he would bike around campus and stop at the local markets to buy his fruits and vegetables. Despite the price difference between regular supermarkets such as Safeway and organic stores or farmers’ markets, Stoehr thinks it’s worth it for all the benefits.

“If you care about the environment, the people working on the farms and your health, those are the three things that play into buying organic food,” Stoehr said.

Stoehr chooses to buy organically because it keeps the soil richer and the workers safer. He knows organic fertilizer is used and pesticides are banned on farms that grow organic food. As the teacher of the AP Environmental Science class, Stoehr is well versed in the effect of industrial farming on the environment, having read books about food and making sure that he’s “up to speed” on the material he teaches in class.

Since all organic food contains limited amounts of chemicals or no chemicals at all, the produce is safer and more nutritious to eat.

Tomatoes grown by large farms are regulated with a growth hormone. This hormone causes growth conditions that aren’t optimal during the season or on the particular farm.

Sarah’s home-grown tomatoes and the ones bought at the market have no hormones that were used in the growing process.

By buying locally from farmers’ markets and organic stores, residents are able to support the community and boost the state’s economy. According to newscientist.com, buying locally promotes biodiversity “at every level of the food chain” and “can benefit the wildlife” as well. For example, Whole Foods supplies local foods that according to their website, is only a seven hour or less car or truck drive away from the store.

Supporting local farms means fresher produce, and the smaller travel time means that the environment benefits as well. The travel time over an ocean or cross-country brings an older version of produce, often traveling a week to a few weeks.

Compared to a seven hour drive, those weeks seem like an extremely long time for food to be carried around in a cargo hold. Preservatives are often used to keep food edible when traveling long distances. This makes it less fresh than local food and not as healthy as organic food.

With fresher ingredients and healthier market options around Los Altos, students are bound to meet the proper nutrition values per day and have a better chance at fighting diseases and other health problems.