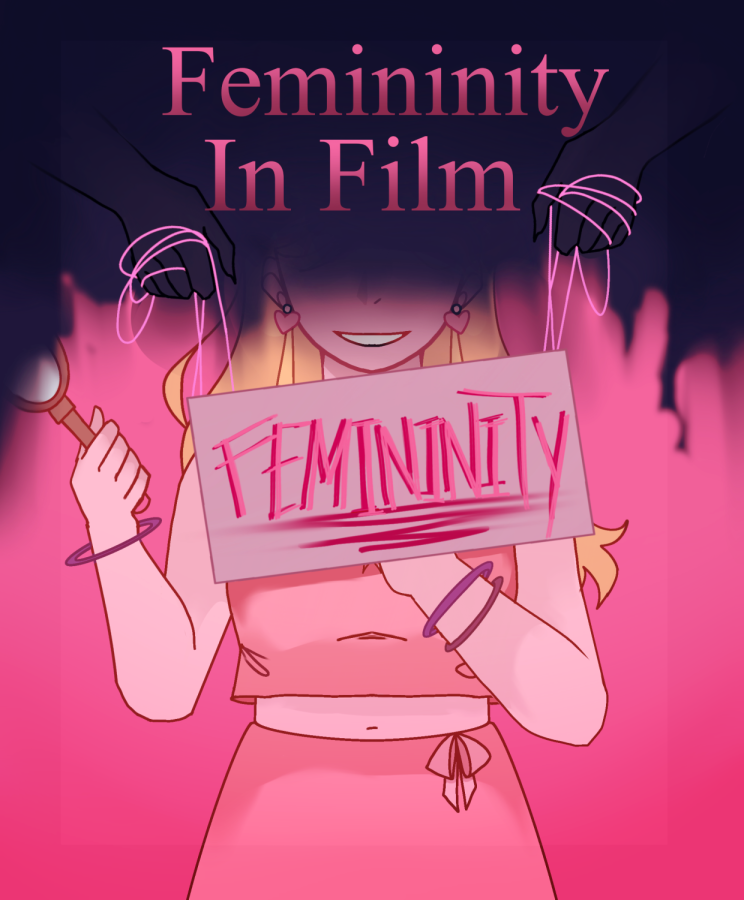

Femininity in film culture: to pink or not to pink

2000s Hollywood’s idea of a supervillain is not always a Darth Vader or Joker. When it comes to the vast majority of chick flicks throughout modern cinema, the color pink has become synonymous with murder.

Popular culture portrays fearless femininity through a dark lens, associating “girliness,” and revealing attire with superficiality and vanity. The pattern of continuously depicting hyperfeminine female characters as evil and not worthy of success is confusing and discouraging; it teaches viewers that it simply isn’t possible for a girl to be both feminine and successful.

Take “Mean Girls,” the quintessential coming-of-age movie for teen girls. Regina George, as we all know, is a modern Medusa — the antagonist to Cady Heron’s nerdy heroine. She’s enviable and beautiful, cloyingly so. So, from the moment viewers see her riding atop the shoulders of fawning teenage boys during gym class, they want her to fail. The movie from then on centers around stripping her of everything society associates with girliness, such as her physical appearance and self-worth, cementing the idea that in order for some women to be good, they must renounce themselves.

But why can’t both things be true? Why couldn’t Regina become a better person, while still expressing herself in whatever form she pleased?

If Regina is the Voldemort of early 2000s high school, Cady is her Harry Potter, the absolute antithesis to everything we are told to despise about “The Plastics.” She is quiet, studious and seemingly unaware of her own beauty. A classic plain jane, Cady is the one we’re told to root for.

When Cady is plunged headfirst into “girl world” after becoming friends with Regina, she loses her intelligent, shy side, and instead appears catty and narcissistic. With this drastic change in personality, the film makes it clear that women can’t be both girly and successful, productive members of society; instead, cinematic women are boxed into strict, archaic ideals of how women should act.

Although “Mean Girls” hit theaters in 2004, the messages sent throughout are loud and clear.

When we look at villains like Regina, it’s crucial that we realize her flaws are not a product of her personality. That bubblegum pink wardrobe and self-admiring attitude, in reality, have nothing to do with who Regina is. But, because these two aspects of identity are so often linked, viewers are led to believe that femininity corresponds to shallowness and malice. This in turn strengthens societal falsehoods that say a woman must choose — will it be preservation of identity, or societal approval?

In “High School Musical,” we’re shown time and time again that Sharpay Evans, the (you guessed it) feminine, scheming she-devil, is supposed to fail.

In contrast, Gabriella Montez is a shy, stereotypical “nerd”; in classic fashion, we’re told that she’s the one to root for. The dichotomy rooted in the film’s message, as well as the trope of pitting female characters against each other, sends painful messages to audiences that the world is strictly black or white. Or, in this case, pink or not.

Through implicit themes, popular culture from the 2000s and prior has defined accomplishment as shutting up and looking pretty. But you can’t acknowledge that you look pretty. We accept you, but only a certain version of you. If you’re smart, you can’t also be attractive. Impossible regulations, unmeetable standards.

Being barraged by media that confines women to fit either one male-driven archetype or the other, makes me beg the question: Why do we as viewers hate when a woman embraces being a woman?

The “not like other girls” trope of recent years cements my belief that we’re taught to reject femininity in order to gain male approval. All things girl-centric are demonized and shunned, seen as signs of stupidity and insipid vapidness. However, the reality doesn’t have to be this way.

In ’90s cult classic “Cruel Intentions,” female villainess Kathryn Mertuil says, “God forbid I exude confidence and enjoy sex. Do you think I relish the fact that I have to act like Mary Sunshine 24/7 so I can be considered a lady?”

After doing some growing and revisiting past cinema, I’ve realized that being a “lady” is a multifaceted, intricate thing. Although film culture as a whole has changed and adapted to fit modern ideals, society still needs to rewire how they perceive femininity and expression.

Femininity is everything all at once, encompassing a wide spectrum of personality and expression. Sharpay and Regina didn’t have to lose for the “good guys” to win, and, most importantly, girlhood should be portrayed as a positive thing that doesn’t define one’s worth, but instead adds to their depth and character.