Fast Fashion: A Trend to End

December 13, 2017

Remember rompers, Toms and Lokai bracelets? Just last year, these necessities were all the rage, but now they sit sadly on Goodwill racks among many other dead trends. So why did these once super-cool fashion trends fall into obscurity?

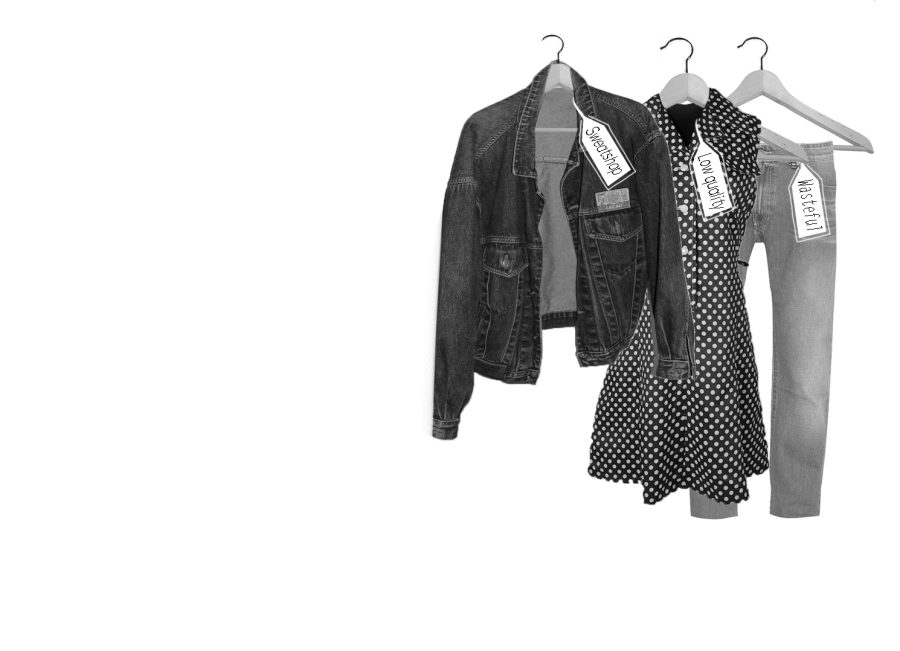

The answer is fast fashion, a term used to describe the rapid cycle of clothing brands which constantly churns out new trends. Fast fashion has transformed fashion for the worse — teen fashion has become a series of short-lived “seasons” in which cheap new styles are worn excessively for a month, then quickly disregarded in favor of the next new fad. The fast fashion cycle also aids teenagers in their quickly-changing tastes. As teenagers stray away from wearing someone else’s logo to establish their identities, they are drawn to the ability to mix and match their own selections.

Forever 21, H&M, Zara and other staple brands all use the fast fashion formula to realize a substantial profit. From 2010 to 2015, these top fast fashion retailers grew an average 9.7 percent per year, against the 6.8 percent from their “traditional-apparel counterparts.” But while it may be fun to see your favorite store filled with new clothes inspired by new fashion trends each time you go shopping, fast fashion has negative environmental and human rights impacts that are often overlooked.

By wasting resources such as fuel and water, the increased production of clothing garments puts a huge strain on the environment. Approximately 20 percent of industrial water pollution is due to garment manufacturing, which is only perpetuated by fast fashion’s production cycle. More than 14 million tons of clothing end up in landfills each year, a number that has doubled in the past 20 years.

Yes, fast-fashion empires like H&M have pledged to increase their clothing recycling in many of their stores, but the implementation of these promises has been disappointing. H&M has admitted that only 0.1 percent of all clothing donated to their new recycling program is actually recycled into new textiles. Those who donate receive vouchers in return, setting off a vicious cycle of buying and recycling which ultimately results in even more clothing waste.

This high clothing production also prompted many retailers to move factories out of the U.S. to third-world countries, where more than 97 percent of clothes bought in the U.S. are made. Many of these factories have been outed by the media for being sweatshops with poor working conditions, with workers earning mere cents every hour and buildings filled with safety hazards. A report by Baptist World Aid gave Gap, Forever 21, Topshop and Nike a C grade or lower on their efforts to decrease “risks of forced labour, child labour and worker exploitation throughout their supply chains.”

Most of us probably realize that having so many clothes produced so cheaply and so quickly has its downfalls. We know that fast fashion isn’t optimal for the environment, and there’s probably something unethical surrounding the treatment of workers who make our clothes. Yet we tend not to worry about it because it’s much easier to keep blissfully buying trendy clothes and forget about all the problems attached to that $10 price tag.

It’s time for a generation known for being self-absorbed to start caring about the effects of where we shop. We can take steps to lessen our fashion footprint; shopping at thrift stores, buying longer-lasting garments and donating old clothes are all easy but impactful ways to do this. By refusing to turn a blind eye to the harms of fast fashion, we can turn fast fashion into another trend of the past.