Economics Meets Legos

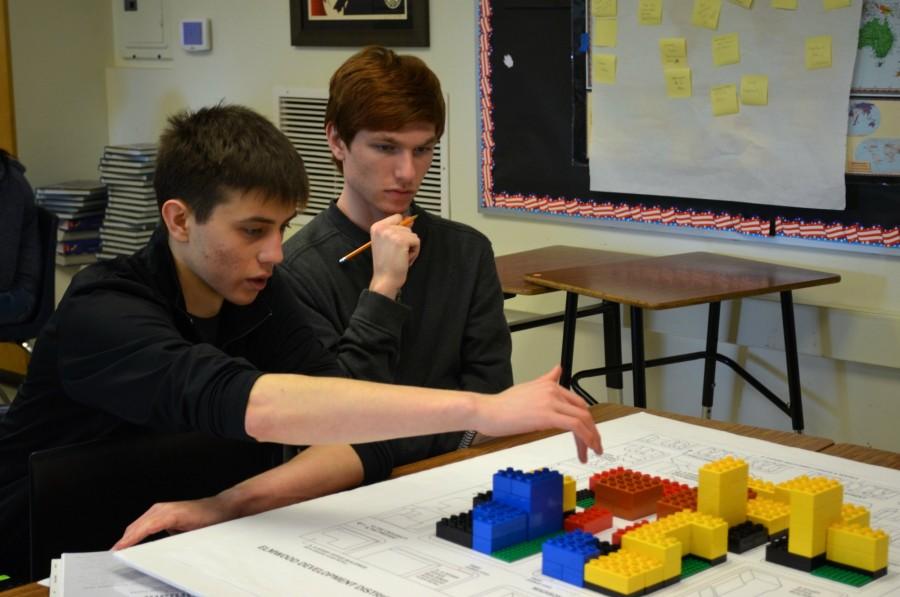

Marketing director senior Duncan Burridge stared intently at the white planning map covered in Lego blocks. An L-shaped high-rise hovered in his right hand. He rearranged the blocks once, twice, three times. None of the configurations worked out.

“It’s worse than Tetris!” Duncan said.

Following a suggestion from financial analyst senior Tiffany Johnson, Duncan rearranged the parking lots around the high-rise, only to elicit strong objections from city liaison senior Josh Kirshenbaum and marketing director senior Paula Navarro. Other group members chimed in as well, offering suggestions and directions.

All together, the seniors make up a mock private development firm tasked with pitching a development plan to “city council,” a group of urban development professionals.

The simulation is currently piloted by economics teacher Joshua Harmon’s three economics classes as part of a 15-hour high school curriculum unit known as UrbanPlan. The curriculum brings development professionals into the classroom to guide students and was created 15 years ago through a partnership between the UC Berkeley Fisher Center of Real Estate & Urban Economics and the national organization Urban Land Institute.

“The mission here for the students is to understand… what it takes to get the built environment,” UrbanPlan program director Marisita Jarvis said. “It’s educating future voters. Lots of local governments make big decisions on land use issues that have impacts on a million things… and we want voters to be informed about what they’re voting about.”

Harmon discovered the curriculum to be a useful educational tool for teaching economics and civics when he was a student teacher at New Technology High School in Sacramento in the 2012-2013 school year. As a new teacher to LAHS, he decided to pilot the program within his three periods of regular economics. Whether Harmon will continue using the curriculum depends on student feedback and his own assessment of the program’s utility.

“This is a pilot semester,” Harmon said. “After we complete everything, we’ll ask [the students] to complete an evaluation… and we’ll sort of digest the positives and the negatives. I’ll also use the rest of the semester as a barometer for how useful this is to frame their thinking about other economic problems. Between the student feedback and my assessment, we’ll decide whether or not we want to bring [the program] back.”

The program splits each class into groups of five, and each student within the group carries out a specific role of marketing director, financial analyst, site planner, city liaison or neighborhood liaison. Together, they must contend with preset economic limitations: five and a half city blocks of space, a minimum 13.5 percent rate of return for investors and $1.5 million in tax revenue for the city.

“They’re confronting the fundamental economic problem of scarcity,” Harmon said. “Everything that they put on the board not only costs them money… but they [also] have to factor in the opportunity costs: What are they giving up to get what they have… [Other] basic economic concepts that are here have to do with supply and demand and generating profits.”

At the same time, economic considerations are inextricably tied to the political realities of demands from various neighborhood interest groups and constituencies.

“Having students think about all those things and deciding who to listen to is an important question as they are developing their own political identity,” Harmon said. “Like ‘How do I want to participate? How do I want to influence the process?’”

This kind of civic-minded attitude is fostered throughout the project, but it comes to the forefront when students deliberate about the inclusion of a homeless shelter and the number of affordable housing units.

“Lots of groups tend to experience conflict over [the homeless shelter],” Harmon said. “In some instances, it’s a financial question, so some groups are like, ‘Well, we don’t want to pay the money to do that.’ [For] other groups, it’s more of a moral question, like, ‘Well, where are the homeless people going to go? We have an obligation to house them.’”

As part of the program, urban development professionals come into the classroom on two separate occasions. Each professional sits with a different group and asks the students to justify the choices they have made, from the perspectives of their assigned roles. For these volunteers, the experience is just as educational.

“It’s neat to look at it from just a layman or citizen’s eyes,” program volunteer and Los Altos City Planning Services Manager Zach Dahl said. “The program gives me a fresh perspective and makes me a better planner because I understand how to phrase things or how to describe them in a way that’s understandable.”

The program culminated with a mock city council meeting, which took place Monday and Tuesday, March 7 and 8. Each group presented its plan to a panel of urban development professionals, who acted as the city council and questioned students on their choices. Ultimately, the group with the best proposal won the bid for development. Some groups, like Duncan’s, were gunning harder for the prize than others.

As the class period wound down, his group remained huddled around the map, shifting blocks this way and that while program volunteer and Bank of America credit products officer Kathy Caisley looked on with interest. She began the class period quizzing each member about their roles, but by the end, she just observed.

“I apologize for sort of dropping out of questions, but I think you guys have a good handle on what you’re trying to accomplish,” Caisley said. A vote of confidence.

The group wasn’t satisfied. They continued to fixate on the arrangement at hand.

“Now all we have to worry about is this giant channel of parking,” Duncan said.