Cheating culture in a year of distance learning

As the 2020–21 school year draws to a close, The Talon took a closer look at the issue of academic cheating within Los Altos High School’s virtual halls and investigated how classes have adapted their structures and expectations across the year.

All students who agreed to be interviewed, whether they committed acts of academic dishonesty or not, did so under the condition of anonymity. Names with the * sign are student pseudonyms.

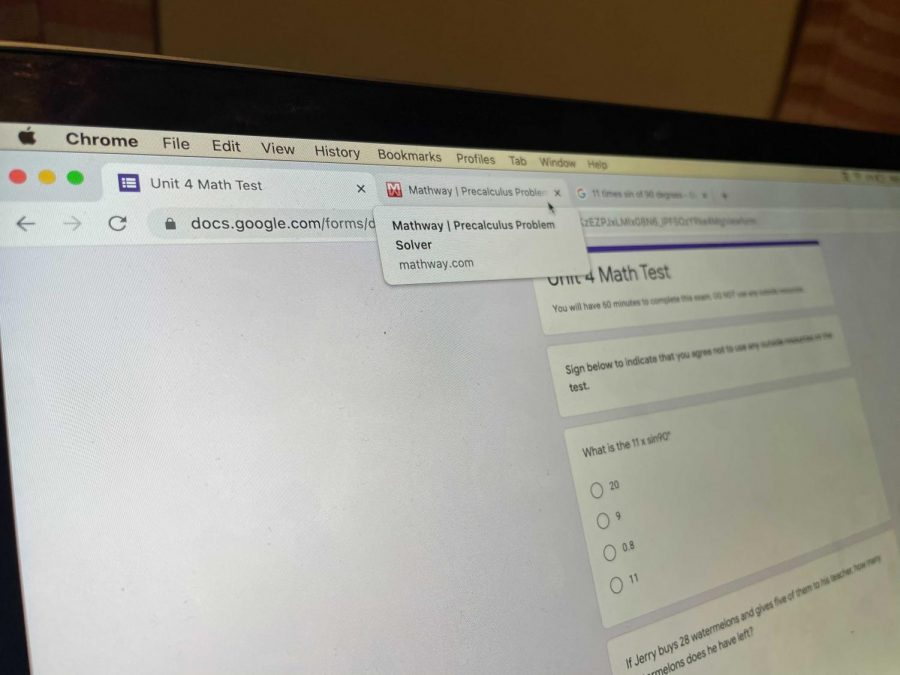

Concerns over academic dishonesty have surged in the past year, stoked by expanded opportunities for cheating through distance learning and the hurdles staff members have faced in trying to curb it. Academic integrity violations — while not higher in the number of reports than past years — have perhaps come with greater impunity than normal, according to multiple students.

“It’s just tempting to [cheat],” freshman Charlie* said. “If there’s a phone right next to you and you’re taking a test, why wouldn’t you just pick it up?”

Los Altos High School isn’t alone in this upsurge, as many academic institutions have come across the same issue. Several cases of cheating were discovered across Mountain View High School’s Chemistry Honors classes in January this year, and approximately 50 percent of Yale undergraduates that engaged in academic dishonesty this year did so for the first time during semesters of virtual learning.

As the school year draws to a close, The Talon took a closer look at the issue within LAHS’s virtual halls and investigated how classes have adapted their structures and expectations across the year. What are behind students’ motivations to cheat? And of course, has cheating really surged?

Evolving expectations

With the pitfalls of secure proctoring amid distance learning, one major dilemma among administrators is whether to allow students to self-regulate their academic integrity versus having teachers alter their curriculum to discourage cheating.

“Yes, academic integrity is the responsibility of the student; however, teachers do need to set up a structure so that we’re moving towards critical thinking,” Assistant Principal Suzanne Woolfolk said. “Are the teachers setting up a structure that lends itself to widespread cheating in distance learning? That’s been the challenge all year.”

Even with changes in course structure, the importance of teachers setting clear expectations of academic integrity and emphasizing the boundaries of what qualifies as cheating is increasingly important this year. Many forms of cheating “depend on what teachers define as cheating,” senior Amy* said. Yet, some raise concerns that students may not be so understood on these expectations or look past them.

“I think that students have tried to be as creative as possible [this year] and reckon things in their own brains as still being ethical,” Woolfolk said. “They’re taking advantage of what they find to be blurry ethical lines that teachers probably don’t see in the same light.”

Consequently, this has led to revised grading and assessment policies within different classes. History teacher Sarah Carlson decided to grade multiple choice exams on completion rather than accuracy because they are “extremely easy to share answers on.” She also allowed students to use notes on exams.

“I didn’t want to put people in a position of being tempted and having an easy way to do something that would be unethical,” Carlson said. “So I designed the tests accordingly.”

Other teachers in the history department enacted similar changes. AP Human Geography classes — often the first AP course for students — openly allowed collaboration on multiple choice exams, but lessened the impact of these exams on a student’s overall grade in favor of classwork.

On the other hand, some teachers, particularly in math and science, are being confronted with more serious issues. These tests, which emphasize one unique correct answer, can prompt more cheating. 30 percent more Yale undergraduates engaged in academic dishonesty in an applied math course than a humanities and arts course this year.

Physics teacher Karen Davis said she has been worried about the heightened ability of students to access online resources. As a result, she spent time rewriting tests with her own questions instead of using preexisting AP problems as she has in the past, whose solutions can be searched up online.

“I had a senior say to me the other day, ‘I think I’ve forgotten how to study this year,’” Davis said. “I thought that was a really telling comment because it shows they haven’t had to study or commit anything to memory this year because of these resources, being able to look things up.”

Davis also said that students’ ability to cheat can depend on whether they’re learning in person or at home, so she decided in some cases to condone practices she normally wouldn’t among students on campus, such as allowing them to look at their homework during an exam.

“When I give a test, I cannot say to the people in class, ‘Okay, you can’t use any of these resources’ while the people at home are,” Davis said. “That’s an issue of equity. I can’t have one set of conditions for the people in class and another for the people at home.”

Beyond changes in grading and assessment policies, teachers can also use and enforce anti-cheating softwares at their disposal. Although Canvas, the instructional program LAHS made the shift to this year, includes an integrated anti-cheating program, teachers have expressed a lack of confidence in it.

One of its features allows teachers to see when students click out of a test window, but Carlson explained it wasn’t worth using it for her instructional time and would rather “just accept that the conditions are different.”

“You’re trying to play whack-a-mole in different ways,” Carlson said. “I don’t know that it’s enough to effectively prevent students from using a different device, a different method for engaging in cheating.”

Teachers have also had malfunctions with Canvas, creating more difficulty with addressing cheating. Due to images on tests not loading for some students, Davis had to move her physics tests to PDF format, which are, by nature, easy for students to download and share.

Cheating surge — is it real?

Each year, an average of around five students are reported to have committed repeated offenses of academic integrity violations. That number has not increased this year, according to Woolfolk.

This falls in line with what some teachers, particularly in English and history, have noticed in their own classrooms.

“I haven’t seen a massive increase,” history teacher Alex Willse said. “If it’s up, it’s up slightly, if at all, but I would suspect it’s no different than what we’ve seen in the past.”

Still, this sentiment may not fully reflect what’s going on behind the Zoom screens or echo across all subject departments. Willse did acknowledge that students are likely communicating outside of the structured class environment and seeking “advantages.”

Davis said that the real issue lies in proving existent cheating, as there’s no question that students are actively sourcing outside of the classroom. She noted that her classes’ grades this year are collectively higher than past years, with particularly inflated test scores, possibly indicating that a surge in cheating took place.

Consequences

When academic integrity violations are discovered, students are dealt with under a framework of “intervention” as opposed to punishment, a shift that occurred approximately seven years ago to help students grow from their mistakes, according to Woolfolk.

LAHS’s policy on academic integrity highlights restorative justice as a method to address cheating. Officially, this entails promoting “genuine learning that leads to a change in behavior, and restoration for the wrongs done to individuals and the community affected by the individual’s action.”

Yet the policy also contains information on the “process for Traditional Discipline,” which appears to address cheating strictly through disciplinary deterrence and the assurance of “severe consequences” upon future violations. A student will be subjected to either process based on an assessment of the academic integrity violation from an administrator in consultation with other staff.

For the process of traditional discipline, violations are placed into one of three categories: Category A, mainly involving collaboration and copying on minor assignments; Category B, which deals with major assignments, plagiarism and material alteration; and Category C, which includes a second offense of Category B, stealing exam information or altering grades.

Corrective action depends on the category and severity of the violation, as well as the student’s history of integrity issues. A Category A violator may get off with a zero on their assignment, a record of their offense in the gradebook and a note home, while a Category C violator will also face ineligibility for all academic honors and a permanent disciplinary record which may involve suspension or social probation.

No changes were made to the LAHS parent/student handbook this year regarding the topic of academic integrity.

Motivations

Although each case has its own underlying reason, common threads between recent incidents of cheating include high concern over grades, desperation and a lack of personal relationships with teachers, according to multiple interviews of students.

Some students report that the benefits of an undeserved A are often enough to allow people to overlook the moral and educational issues associated with cheating.

“When you’re given one chance to get a B or an A in a class, you’re going to want to cheat,” senior Jane* said. “You’ll want to do your best on the test, which doesn’t necessarily mean the best of your knowledge, [but rather] the best of your resources. If the resources [to cheat] are at my disposal, I’m going to use them.”

Some cases are more spur-of-the-moment. Charlie resorted to plagiarism after experiencing frustration in creating an original poem for an English class. He used a website to generate a poem, then edited it, but was caught through the widely used plagiarism detection software Turnitin.

In a similarly impromptu fashion, Amy admitted to searching up concepts like formulas on certain tests upon forgetting content amid the pressure of the testing environment.

“When I’m taking a test and I forget the formula or something, I wait for a second and try to think of it,” Amy said. “And I can’t think of it, so I’m going to go look for the formula. And obviously, I feel very, very nervous when I do that.”

Even when students seem to be aware of the risks and ethics behind cheating, academic dishonesty continues to take place.

Student frustrations

As much as teachers come up with new ways to address cheating, some students are frustrated by the perceived rampant cheating and lack of clarity on how teachers are addressing it. Amy said that teachers “haven’t addressed [cheating], just highlighted it,” and referenced how while her math teacher outlined what was considered cheating, they did “nothing to stop [cheating]” during tests.

More so, some are convinced that an end to cheating would require a much more radical shift in mindsets, not just better clarity on addressing it.

“Nothing the District can do is going to mess with students using the Internet or using each other as resources,” Jane said. “In order to discourage cheating, you need to de-emphasize the importance of tests. I would say the District has to de-emphasize grades in general and foster an environment where learning is encouraged rather than grades.”

LAHS’s official policy on academic integrity and cheating can be found here.