SAN JOSÉ MUSEUM OF ART — Three art exhibitions, “North Star,” “Beta Space,” and “Calder: At Home, Among Friends,” are on view on the San Jose Museum of Art’s upper floor until mid-summer. Curated by Lauren Schnell Dickens, the exhibitions are different, peculiar, unexpected — not what one would imagine to be prototypically “good art” — but they stick with you in a good, itchy way.

The museum offers just enough interest to keep you wandering for an hour or two, without overwhelming you. And if you’re looking to make a day of it, I’ve compiled an unofficial (and budget-friendly) field guide: where to eat, what to see, and what in the art to look for.

♦ Scratch cookery: cozy, pop-up-style brunch spot, known for their smash burgers.

♦ Pastelaria Adega: a Portuguese bakery offering warm custard tarts and the like.

♦ The Nest Asian Bistro: a Vietnamese restaurant, offering Pho and Banh Mi, plus wings, ramen, and quesadillas.

Here is some context to know about the exhibitions:

The artist Kambui Olujimi celebrates Blackness, as well as the cosmos and gravity, in his solo exhibition “North Star.” And he does so in characteristic fashion, resisting the tendency of modern art to deliver didactic messages — he’s not looking to moralize you, and stays more quiet, sensitive. We are used to pieces that preach to us, that are more concerned with the aligning of oneself ideologically than with individual or personal expression, but Olujimi’s paintings reject that mode. You should expect a more emotional response, without being told what to think.

On view from Friday, November 1, 2024 to Sunday, June 1, 2025, “North Star” comprises large-scale watercolor and ink paintings, a site-specific mural, a film, a new sculpture, and a video installation. The exhibition opens with 12 large ink paintings that depict Black bodies drifting in a state of emptiness (Olujimi called it “vacancy” or even “entropy”). These figures are echoed on the walls behind them, through video projections.

This is a double-natured exhibition: it can be interpreted as a contribution to the discussion about Black experience in America, but then there is the actual, direct aesthetic experience, which is enjoyable on its own, even if taken out of its ideological context.

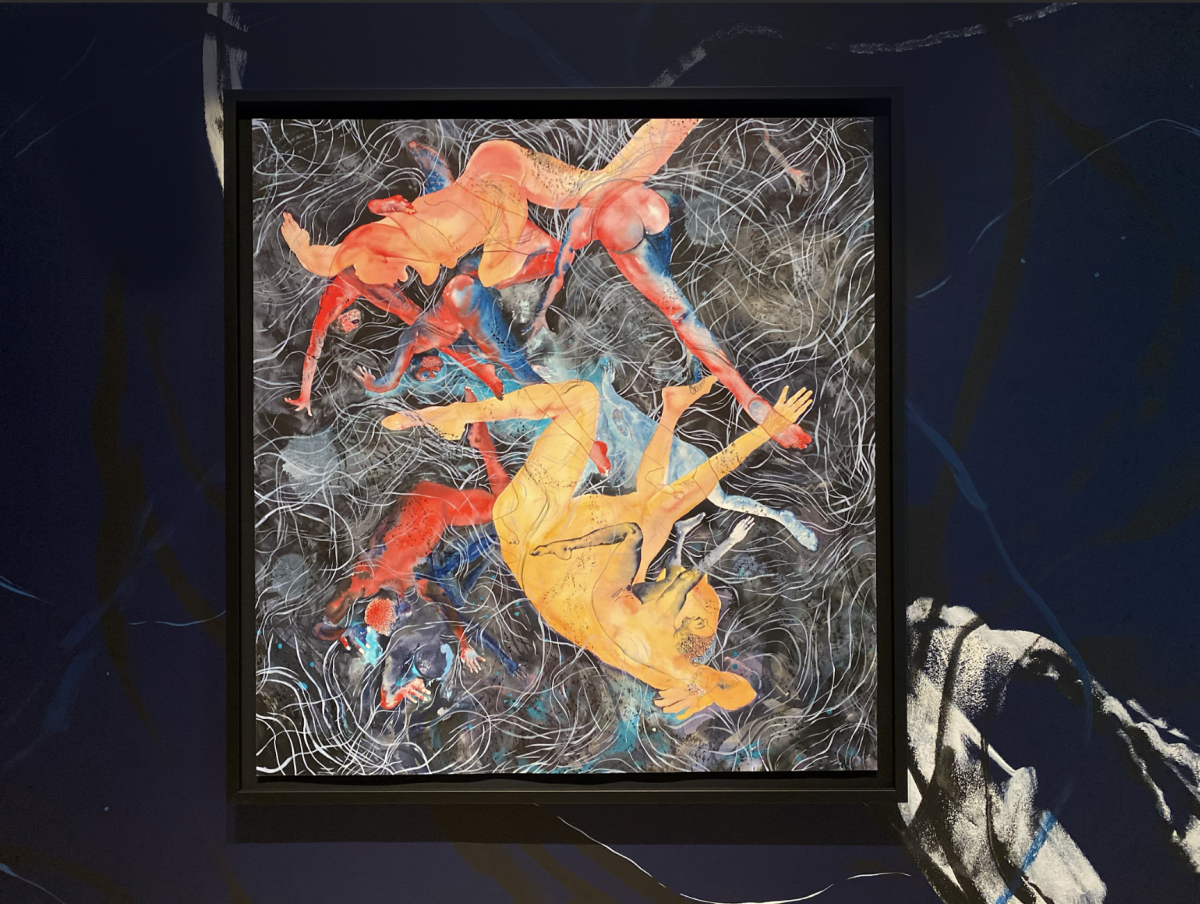

I found the space itself to be most enjoyable of all. The twilit walls, painted indigo, are streaked with white, mutable as light against a moving tide. The entire room is dark, except for the figures in the paintings; colored with vibrant shades of reds and ochres and beiges, they bring forth lightness.

Much like the nature of the gallery room itself, Olujimi himself describes his art to be “something that seems sort of familiar, sort of foreign.” The bodies are taken out of their everyday context, but their constitutive form is preserved — we do see familiar motifs of Black art in Olujimi’s art, but the exhibition feels personal, unique to him. This same feeling would describe his own vision regarding Blackness, anti-Blackness (or the lack thereof), when compared to his contemporaries.

“The Black body is too often saddled as a station of trauma and violence,” Olujimi wrote on his website, and so his work doesn’t touch upon Black suffering but instead memorializes “Black joy,” through a mode which he calls Black Rhapsody.

“The American context has sought to subvert Black joy, systematically, in a way,” Olujimi said. “But Black Rhapsody is a kind of elation, where there’s a kind of acknowledgement about the way that joy is ricocheted and concealed and protected.”

This “joy,” this “rhapsody,” happens in one part mentally (through freedom from oppression) and in another part physically (through having the freedom to physically float freely), and together they create something larger, something communal.

We see it in “Folding Mirrors,” an entwinement of multiple figures — a person and (perhaps?) their loved ones — that are yellowish when close to us, and blueish when afar, forming ribbon-like ripples with their movement. The piece is beautifully aesthetic, with the vibrant colors of the body, but then at the same time, Olujimi is making us think differently about Blackness by removing black color as a definition.

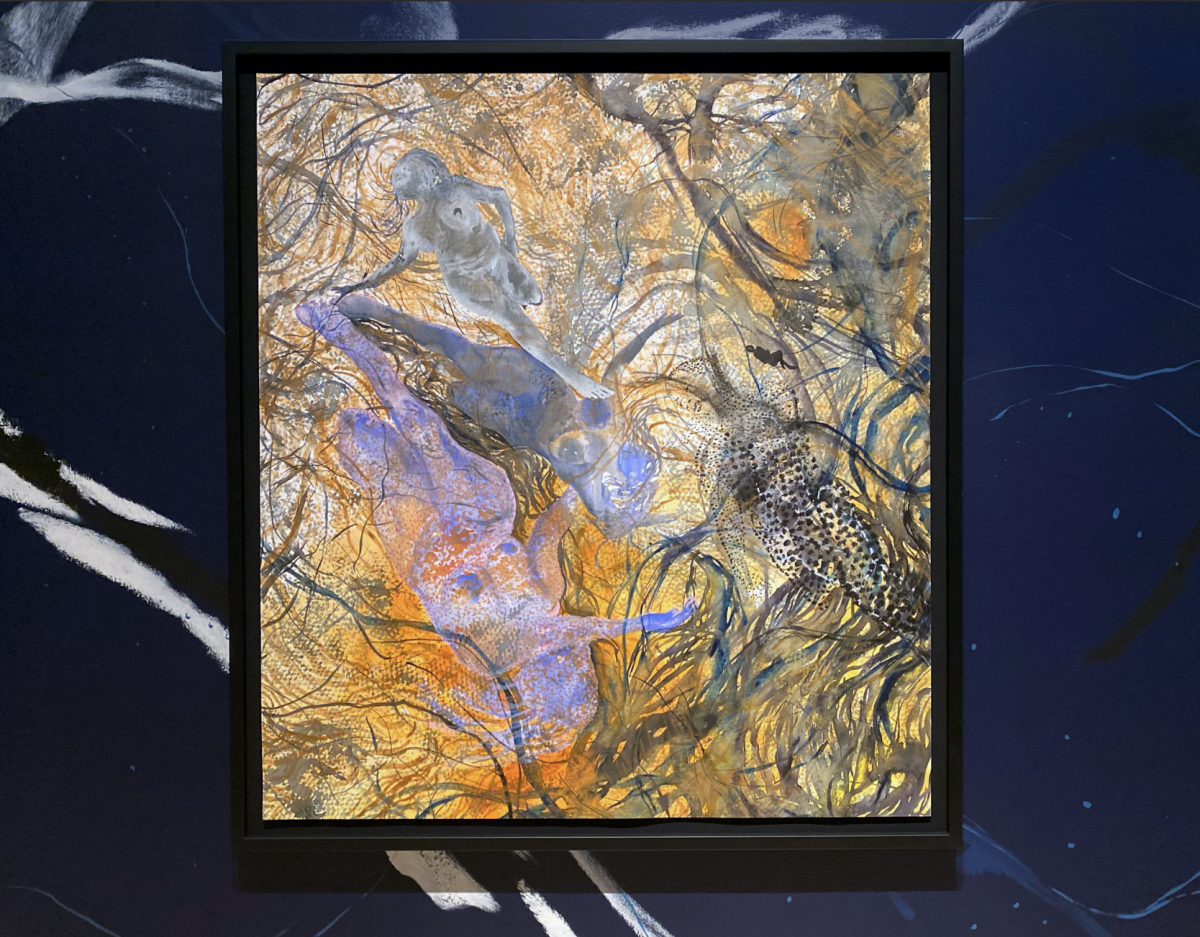

Each piece takes place in a different space, and you can imagine what each of the figures could be doing there. In another piece, “Ghost Ledger,” a female spectral body — and many more, some less conspicuous than than others — inhabit a jungle-like setting, with a strange dotted pattern evoking a leopard, or maybe some kind of strange bird. Or perhaps, the orange-brown brambles are really flames, and the black swirls are really plumes of smoke.

Olujimi emphasizes looseness, chaos, in his backgrounds, which all contain dynamic streaks and swirls of paint. But in some of his paintings, the people inhabit a very cosmic space, a place that feels greater than us.

“Earth is a very, very, very, very small part of our solar system, which is a very, very small part of our galaxy, which is an infinitely small part of a universe,” Olujimi said. “I look at scale a lot. This very small planet has been around for about four and a half billion years. The existence of humans is tiny. It just reminds me of what I get to be a part of, that I am not the world.”

In “Even More Beautiful Than I Ever Imagined,” there’s energy, around peoples’ outsized figures, as if the physical body is no longer there, and our existence has been spiritualized. The dots around the body are like energy particles, localized around the central, glowing body, as iterations of other bodies float around like spectra.

This energy is palpable, extending towards you. You look at the infinite, receding, cosmic space, and you begin to feel that the space you’re standing is also “space” in the other sense, the cosmic sense, as if you are also floating. And so, in a way, the space from inside the paintings extends outside, to where you are; by looking at the paintings, you are experiencing that same vicarious liberation and rhapsody.

The ocean, in its mysterious, intriguing breadth, has been a recurring motif in art for centuries. Most of it has captured its literal beauty: in the waves, in the way pellucid the water reflects and distorts light, in the pretty barnacles at the ocean floor. But here at the San Jose Museum of Art, at the monumental installation “Beta Space,” artists Patty Chang and David Kelly represent the ocean as something entirely symbolic, as something technological and mechanical that fits together. One part, “Stray Dog Hydrophobia,” comprises the large wooden structure; the other, “Chakra Sculptures,” flanks the structure on the side, with its mesmerizing deep-sea specimens.

The exhibition is captivating in other ways, too. Seeing it feels like a treasure hunt, or solving a puzzle. The exhibition’s filled with easter eggs that are not shown explicitly, but can instead be inferred; they make you wonder why everything was there. It was enjoyable to discover these things: that the entire wooden structure was modeled after the human nervous system, that the ink on the plates come from poetry and legal texts, that the same plates were modeled after Secchi disks used to measure water clarity.

“An interesting way to engage with the artwork is through a certain kind of inquiry, that lets you make your own meaning,” museum curator Juan Omar Rodriguez said. “For example: ‘Where did these plates come from? Why are these specimens held in these ceramic sculptures with glass — where are these rocks?’ There’s a lot of possibility and wonder and meaning that could come from just asking questions.”

But to me, the highlight of the show belongs to “Chakra Sculptures,” which elects to show us the ocean’s delicate, ethereal beauty, compared to “Stray Dog Hydrophobia,” which shows the ocean as something macroscopic, greater than us. Towards the sides (against the walls), the roughness of the wood structure is juxtaposed by the reflective glass, the dainty porcelain, and the pristine white pedestal upon which they’re placed.

These sculptures are beautiful by themselves, even if taken out of the broader environmental and anthropological contexts, surrounding the ocean. Bone specimens of marine life are displayed inside the jars, and all sorts of miniature porcelain pottery garnish the sides — a reference to porcelain that fell from shipwrecks when being exported from China to Europe, and accumulated on the ocean floor.

“Even just having those specimens in the exhibition brings in the language and world of science,” Chang said. “We very specifically wanted to have artists make handmade glass containers, and then to hand-make unique platforms to hold them, to bring it out of the purely scientific world and to elevate it into another space — to imbue it with something spiritual, or that you could call magical or imaginary.”

You cannot summarize the ocean — that vast ecosystem, repository of anthropology and human history. And so, rather than attempting to contain it, “Beta Space” embraces its contradictions, its complexity — instead electing to show the ocean in as many angles as possible, and as a place of intrigue and potential.

In what perhaps best captures the gestalt of the exhibition, Chang asks: “In a place where humans can’t go even two miles below the ocean, where there’s no sunlight because it’s so deep and pitch black; how can one make a connection to, or even try to imagine, what life was like there? Or try to preserve it?” We are suspended in her asking, somewhere between wonder and reverence.

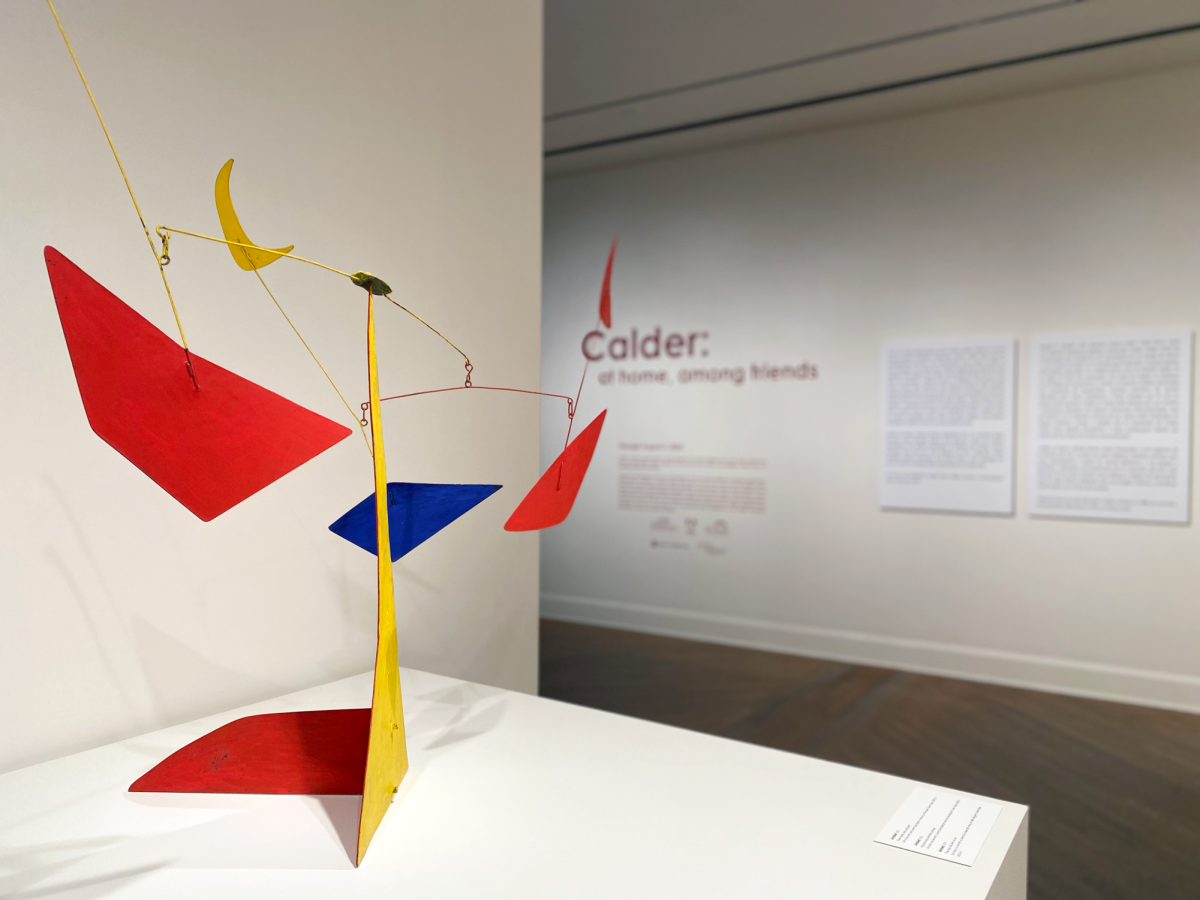

In another room, the collection “Calder: at home, among friends,” feels closest to abstract “contemporary” art, and at the same time feels more delicate than the large-scale paintings and installations of “North Star” or “Beta Space.” The exhibition is on view until Sunday, August 3, 2025, and comprises small objects and gifts that the artist Alexander Calder made for close friends and relatives during his lifetime.

Calder (1898-1976) was best known for his large, iconic mobiles, monumental sculptures, and stabiles. Most of his works have an imposingness to them; they’re meant to be admired at a respectful distance, and can feel distant at times, almost untouchable. But here at this exhibition are his more modest works, ones that he made for others as simple gifts, for people not much different from us.

The curators’ original vision for the exhibition was to make the space look like a thrift shop, and drew upon commercial spaces as much as domestic ones. At the same time, it elicits the ambiance of a living room or workshop, or some kind of imagined home, in which “you feel an intimate connection to these objects,” Rodriguez said.

All of the pieces here have so much personality, youthfulness, to them; though they have that contrived, industrial feel to them — and may come across to us as synthetic-looking — they don’t at all feel cheap or unremarkable.

If you like jewelry, you’ll be drawn to the minute detailing and wearable elegance of some of Calder’s handmade pieces. If you like animals, you’ll love the wire figures, of horses, cows, and all sorts of birds, imbued with just the right gesture to make them come alive. And if you’re just someone who likes to see the “closer” side of artists we usually reverently laud, then this is an exhibition worth lingering in.

Museum Hours

Monday – Wednesday: Closed

Thursday: 4:00pm – 9:00pm

Friday: 11:00am – 9:00pm

Saturday & Sunday: 11:00am – 6:00pm

How to get there

The Museum is a 0.7 mile (15-20 minute) walk from the Diridon station on Caltrain.

90 minutes of free parking is available in many San Jose parking garages.