The Hidden Issue of Teacher Stress

Teachers grapple with high stress levels that can cause real ramifications, but it goes relatively unnoticed amongst growing conversation about student wellness.

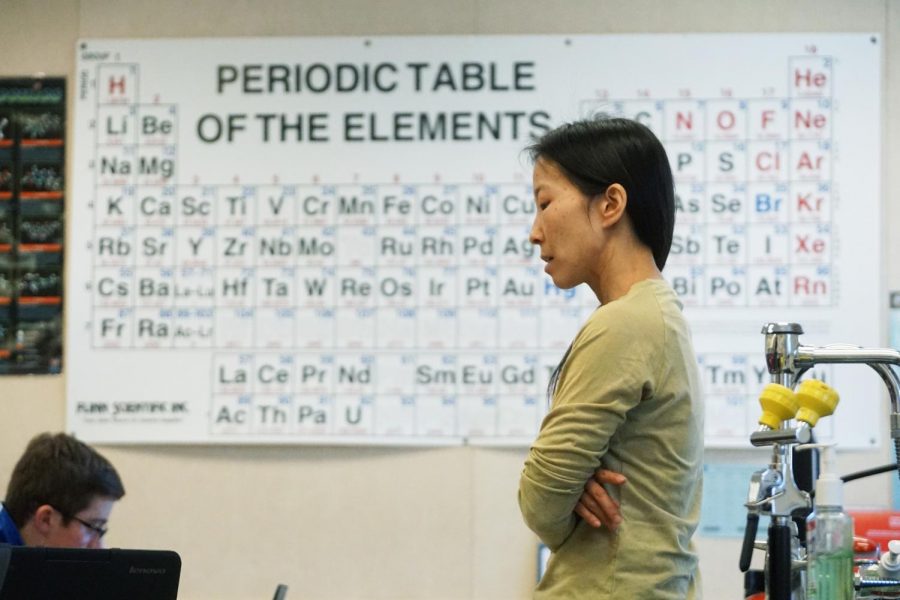

Chemistry teacher Trina Mattson instructs her chemistry class. Mattson lost sensation in the left side of her face in 2009 after teacher-induced stress impacted a nerve, and hopes others don’t overwork themselves too. Kylie Akiyama.

February 13, 2018

In 2009, chemistry teacher Trina Mattson started talking to doctors about sharp pains she felt and a loss of sensation in the left side of her face.

“It got to the point where I couldn’t function at all,” Mattson said. “I couldn’t eat, I couldn’t open my mouth more than an inch.”

For the past semester that school year, Mattson had constantly worked overtime and didn’t recognize her high stress level — she thought it was normal. After doctors couldn’t identify the cause of the issue, she admitted herself to a holistic treatment facility. She was diagnosed with stress-induced trigeminal neuralgia, a chronic condition that affects the nerve controlling sensation from the brain to the face.

“It was a wake-up call that stress is a real thing and I need to manage it better to become the teacher I want to be,” Mattson said. “To this day, I still can’t feel the left side of my face at all.”

Mattson isn’t alone in her stress. While students spend hours studying for exams and doing homework, teachers are also working, often taking their jobs into their homes. But teacher stress is much less talked about than student stress, even though 46 percent of U.S. teachers say they feel high daily stress, according to research-based consultancy company Gallup.

Since this incident, which occurred before Mattson began teaching at Los Altos, she has tried to manage her stress levels by setting more realistic goals and becoming comfortable with saying no to more work. She finds that devising a balance between her work and health by creating detailed schedules ensures she doesn’t overwork herself.

For teachers like Mattson, learning to manage stress has been crucial for their own mental health and the quality of their teaching. Teachers said high daily stress affected their health, teaching performance and quality of life, according to a study from Pennsylvania State University. And while the administration helps by offering mindfulness resources and stress-managing techniques, stress persists.

Social studies teacher Sarah Alvarado believes teachers have three jobs: teaching, lesson planning and grading. For her, executing all three jobs well at the same time is nearly impossible, so she tries to focus on teaching and either lesson planning or grading each week.

“If teachers don’t put boundaries [on how much work we do], we will never stop working because there’s always something to do,” Alvarado said.

“People are more important than papers, and sometimes you have to choose people over papers, whether that be interacting with parents, students, other teachers or your own family,” English teacher Margaret Bennett said. “Most students recognize that and as long as you get the work back in a reasonable time, most students understand.”

For teachers, self-caused pressure to provide constant feedback for students also causes them to use personal time to finish grading, with many teachers dedicating part of their weekends to work.

“Ideally, I wouldn’t want to grade over break, but realistically, it happens,” math teacher Eunice Lee said. “Even if it’s a homework-free weekend for the students, [that’s not] the case for the teachers. The break time is our opportunity to get caught up.”

Moreover, students can often unintentionally increase stress levels by turning in late work near the end of a semester and creating an influx of new papers to grade.

“It wasn’t until day one of when I first started teaching [that] I realized how much work teachers put into the profession,” Lee said. “I don’t blame the students if they don’t know [about teacher stress], because I didn’t even know until day one of working as a teacher.”

Another source of stress comes from taking on new classes, especially AP classes or subjects that teachers are unfamiliar with. New classes often require teachers to develop new skills, from grading with unfamiliar rubrics to teaching test-specific skills.

“Teaching a new class requires a level of work and engagement for a teacher that makes you feel like a first-year teacher all over again,” Alvarado, who replaced her two CWI classes with AP US History classes this year, said.

Teachers approach dealing with stress in a variety of ways, including taking advantage of mindfulness conferences for educators and setting aside time for themselves to exercise or meditate.

Lee sets boundaries on the amount of time she spends working outside of school, choosing to stop grading papers after 7 p.m. and continuing unfinished work the next day. Alvarado believes that showing students how busy she is by doing things such as sharing her calendar helps students understand her workload better and helps her manage her time more effectively. Mattson organizes her schedule into time blocks and ensures that she leaves “down time” in her schedule, a system she encourages students to keep in mind as well.

“I would tell students with overloaded schedules, ‘I know these are your college goals, but if you continue the path you are on, sooner or later you are going to burn out,’” Mattson said. “Please learn how to create balance in your life early on, otherwise you might have a mental or physical breakdown when you can’t take it anymore. Trust me, I know. It happened to me, and I don’t want it to happen to anyone else.”