A decade after his last film, acclaimed Studio Ghibli film director Hayao Miyazaki spent seven years writing and directing “The Boy and the Heron,” a coming-of-age fantasy film released on Friday, December 8 of last year. The film highlights the complexities and beauty of life, even in spite of all its imperfections; it’s a treat for old Ghibli fans.

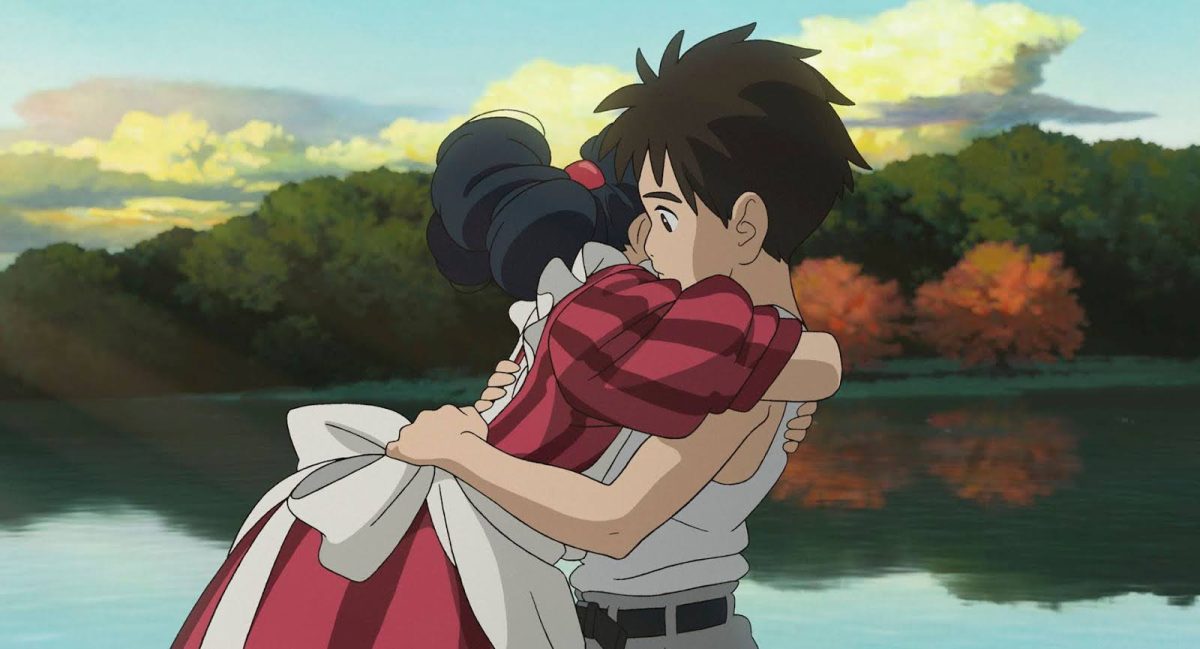

In “The Boy and the Heron,” after protagonist Mahito Maki’s mom, Himi, dies from a hospital bombing, Mahito struggles with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and stays at home, where a talking heron residing in his backyard bothers him nonstop. But through this heron, Mahito learns of the presence of Himi in a place between the living and the dead — and he embarks on a journey to find her. During this journey, he meets many family members, including his granduncle, Himi, and his stepmom, Natsuko.

“[Mahito] is not your typical nice and meek boy, is he?” Studio Ghibli co-founder Toshio Suzuki said to Entertainment Weekly. He has a darker side in him. He’s growing, and he’s very confused. That mirrors how Miyazaki is.”

Many of the events in the film reflect Miyazaki’s childhood, such as his own PTSD from growing up during World War II, his mother’s hospital stays and his dad’s career as a military manufacturing firm director. Himi strongly resembles his mother, who was known for constantly questioning social norms and has inspired many past Ghibli characters, like Dola from “Castle in the Sky.”

Miyazaki films leave his audience wanting more. As the layers peel back and the plot unravels, Miyazaki’s creations are still immersive — even a decade later.

The most complex part of “The Boy and The Heron” is its characterization. Miyazaki weaves a multifaceted personality into each character, although not necessarily a likable one, making them relatable and realistic.

“There are all these other characters that appear in the film who are based on people he has worked with over the years,” Suzuki said. “He wanted to pay tribute to them and express his gratitude for their support throughout his career.”

That complexity sometimes works against the film: some characters take on multiple, overly convoluted forms that complicate the plot. But, overall, it’s these characters’ nuances that make the film seem more tangible and appealing to viewers who crave authenticity.

The film’s anime stylings also make the film feel realistic and humanlike: Vibrant splashes of color and the seamless transitions between thousands of hand-drawn 2D frames makes Mahito’s life feel three-dimensional. The magical chords of the theme song played in the credits, “Spinning Globe” by singer-songwriter Kenshi Yonezu, also elevate the film’s emotional punch and bring a bittersweet end to this seven-year production. The pauses and passages of intensity alike are in just the right places, pulling at the audience’s heartstrings.

“Seeing [Miyazaki] sitting right there in front of me, listening to it, he even cried,” Yonezu said.

Adding another layer of intricacy, Miyazaki titled his film: “How Do You Live?” in Japanese. This question is touched on throughout the story, ultimately arriving at the idea that we don’t always have to understand what’s happening or why, but we should live on regardless, fighting for tomorrow. Like Mahito, the audience is thrown into a world of chaos, diving into a foreign land between life and death.

Throughout the film, Miyazaki asks the audience to contemplate what can be considered beautiful or flawed. In the eyes of the protagonist’s granduncle, the world is full of flaws that need to be fixed. Yet, after realizing life isn’t black and white, and that nobody chooses the life they are born into, Mahito decides that these flaws are what makes life worth living. When his granduncle — master of the magical realm — proposes the elimination of these flaws in the real world, Mahito is desperate to return home and experience the reality of life, regardless of its brutality.

Miyazaki reveals the hard truth: there is ugliness within all beauty, and vice versa. With death always comes life, and with life always comes death. His message uses the familiarity of past Ghibli films to bring light to the questions they all pose: Where is the line between right and wrong? Since many of Miyazaki’s films share similar themes surrounding morality, this film may come across as predictable or repetitive to Ghibli audiences. However, I think it’s perfectly representative of reality; life continues, and “The Boy and the Heron” is only one thrilling chapter of Mahito’s life.

Miyazaki’s background makes his most personal film impossible not to appreciate; the film’s recent Golden Globes Award speaks volumes. The complexity of Miyazaki’s messages and characterization makes “The Boy and the Heron” a film worth watching many times. Even with a relatively simple plot, every scene and artistic choice is carefully and cleverly embedded with deep meaning, leaving the audience thinking. Miyazaki does a spectacular job of describing the reality of life, but also emphasizes the choice to live on because it’s worth it. This way, he urges the audience to do the same. He urges us to appreciate what we have and fight for those who are dear to us. So fight.