Speech & Debate: the fight to end sexism is not over

March 30, 2023

From presidential debate stages to the tiny classrooms that host high school debate rounds, a debate is a performance won through the art of persuasion.

In theory, the most persuasive speaker with the best argument should win over the audience. In practice, however, debate rounds seem to be judged on all sorts of things that have nothing to do with arguments — and one of those things is gender.

“The debate community reflects a microcosm of broader society,” Mountain View–Los Altos Speech & Debate team head coach Julie Herman said. “The same kinds of problems that you see in broader society are here — magnified by the specific values that you get in a competitive space.”

According to a recent study that analyzed the results of 125,087 Public Forum debate rounds, a debate team of two women is 17.1 percent less likely to win against a team of two men. Another study found two men have a 37.6 percent higher chance of winning over two women in the same debate format.

Within the MVLA debate team, the effects of this disadvantage can be felt in and out of debate rounds. Out of many issues, female debaters are told to change the way their voices sound and to dress a certain way in order to be taken seriously. They’ve been fighting these double standards for years.

Los Altos High School students on the Mountain View–Los Altos Speech & Debate team pose together for a picture.

Appearances can be deceiving

Attire has always been ingrained in debate culture. While changes have been made in recent years, most debate tournaments require “formal attire.” However, it’s widely agreed that these dress codes and judge expectations perpetuate gender stereotypes; they emulate archaic social expectations of dress, assigning formal skirts to women and a suit and tie to males.

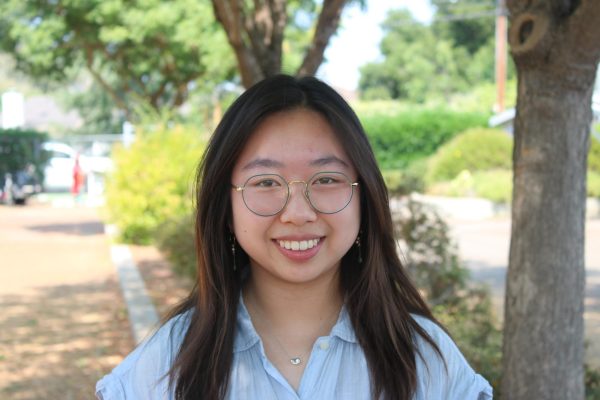

“Male debaters definitely have more wiggle room for what is considered ‘professional,’” former LAHS debater Julia Chang, 19’ said. “A male with messy hair or unironed clothes may be dismissed or excused for ‘just being a boy,’ or even applauded as evidence that they had prepped all night prior to the tournament. Meanwhile, women are expected to show up well-dressed and groomed.”

In the professional world, women of color are oftentimes penalized for a perceived lack of professionalism, which studies have shown to be rooted in prejudice against Afrocentric or ethnic hairstyles. However, many disagree with the burden this places on minority members in debate. Anagha Rajesh, president of the MVLA Speech & Debate team, has had her fair share of concerns about being pigeonholed due to outdated regulations.

“There’s a lot of classism that goes into saying that being professional means you show up wearing a suit,” Anagha said. “When you have an activity where you’re saying people will learn to be professional, you need to relearn those things.”

As gender roles become less stringent and the Speech & Debate community has begun altering its regulations to fit a whole spectrum of identities, the MVLA Speech & Debate Parliamentary team has made changes to its dress code. Anagha comments on the positive change to the debate environment and its impact on students.

“At Parliamentary tournaments, you’ll see a lot of kids in jeans and a T-shirt, and I think that’s the direction we should be moving in for sure,” Anagha said.

It’s an intrinsic aspect of a changing world: As social norms ebb and flow, they also grow to incorporate all groups, extracurricular activities and communities. Speech & Debate can wait for societal change to reevaluate its norms, or it can lead the way.

Speak loud or hold your peace

Misogyny is also prevalent in the debate community because judges assess members of different genders differently when it comes to speaking and presentation abilities. Based on the inequalities surrounding sexism in broader society, the public speaking and presentation aspects of debate magnify gender-based stereotypes and perceptions.

“The ability to speak loudly or speak confidently gets interpreted very differently on somebody who’s masculine-presenting versus someone who’s feminine-presenting,” Herman said.

If female debaters raise their voices, they’re combative and aggressive. But if they’re not loud enough, they’re too passive. According to Public Forum Speech & Debate Coach Kim Ong, because of this burden, women are forced to work with this additional pressure from stereotypes compounded by the older generation — specifically, parent judges.

“Male students typically don’t have the issue of being told that they need to speak up,” Ong said. “Typically, the male students will get more of a pat on the back. The female students, on the other hand, are typically slapped in the face with ‘you need to speak up more,’ or ‘what you said wasn’t as poised as your opponents.’”

In general, debate can be perceived as an argument between two teams. Societally, it is more natural for men to get into fights or arguments, but the expectations placed on females are different, according to former Speech & Debate president Angelina Lue, ‘21. As a result, female debaters have been told to speak in a different way.

“I kind of learned how I had to tone down sometimes,” Lue said. “It sucked and was unfair, but it did affect my performance, and that is kind of just the patriarchy we live in.”

Specifically, one aspect of debate that has historically favored males are speaker points. During evaluations, judges decide the round’s winner based on the strength of each argument, then assigns a point value of up to 30 to each debater to assess their speaking performance. However, these speaker points can often be arbitrary, as judges’ perception of strong speaking is subjective.

“When it comes to speaker points, people who talk like white male politicians usually tend to get more speaker points,” Parliamentary co-captain and senior Maya Yung said.

Since speaker points can heavily rely on a judge’s biases or stereotypical influences, Herman has started eliminating them at MVLA-hosted tournaments.

“I don’t think there’s a reason that we should continue to use a metric that seems to be more a reflection of society’s prejudices than an actual reflection of the value of students’ skills,” Herman said.

Commodification of serious issues

Speech & Debate, by nature, allows students and mentors alike to delve into difficult and layered topics in order to unravel causes and solutions; while an intellectually stimulating and important activity for youth, concerns can be raised about how some topics in debate are broached. Anagha has experienced firsthand the effects of what she attributes to being the “luxury of distance.”

“People are sometimes not cognizant of the fact that the issues they talk about affect their opponents and the judges in the room,” Anagha said. “For you to sit there and debate something in a purely intellectual manner is a luxury that’s often only granted to a certain demographic.”

The lack of sensitivity that some debaters with an inherently more privileged mindset approach issues with can have real impacts on marginalized groups in the debate community. For example, Anagha discussed a topic she once debated relating to radicalism and social justice, where male opponents would often “commodify [the topic] for the sake of winning the round.” The main goal for many competitors revolves around emerging victorious from a round rather than gaining new insight into worldly or polarizing issues. The arguments in that round surrounded sexual violence against women, and when raised without sensitivity and empathy to the topic, female and non-gender conforming debaters were the ones who were affected.

“I think you can discuss these sensitive topics in a debate round, but it’s about doing it in a way where you realize debate at its core is an educational activity where you learn about current world events and you look at how to solve them,” Anagha said.

Debate, she believes, is a multifaceted activity, and while some aspects breed insensitive approaches to nuanced issues, the other side of debate allows for solutions to be discussed in a nurturing, thoughtful environment.

“The point isn’t to win rounds; when you have students whose mindset is purely ‘I need competitive success,’ that fosters this kind of issue where people are commodifying things for the sake of winning,” Anagha said. “When you have a group of students who have the mindset, ‘I’m using Speech & Debate to advocate for things I’m passionate about,’ there’s a lot more humanity involved.”

Speech & Debate thrives off different perspectives clashing and begetting new responses to different world issues. MVLA’s Speech & Debate team harbors a team of coaches and high school students, all willing to speak up when an argument can be improved.

Breaking glass walls and ceilings

Research shows that female debaters are 30 percent more likely to quit Speech & Debate than male debaters. Not only does this exacerbate disproportionate gender representation within the activity, but it hints towards a larger, looming problem.

Ostracization in academic environments is not a new notion. Women in the workplace have spoken of experiences of isolation and unnecessary obstacles throughout their professional careers. These can be described as “glass ceilings,” when referring to the underrepresentation of non-male identifying figures in higher levels of an organization, and “glass walls,” when they are concentrated in a particular field of work.

Glass ceilings are made for shattering, and steps are being taken to eradicate, slowly but surely, the disparities within the debate community. At MVLA Speech & Debate, the past year has seen the inclusion of the Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Committee, and MVLA already frequently corresponds with AVID and Alta Vista to support the incorporation of diverse ethnic and gender groups on the team.

Three debaters at Coast Forensic League Superdebate jump for a picture.

Fighting back

“Welcome to the protest.”

In the 2021 Tournament of Champions (TOC) — the Super Bowl of the debate world — the two top Public Forum debate teams participated in a rather unconventional debate round. Instead of debating the assigned topic, one team chose to read a speech on how transgender debaters are excluded from the debate space, explaining that using the round as a platform to call out discrimination in the debate space was the only way to make real change.

“This round is going to be a debate about debate,” the winning team said. “We have tried politeness, we have tried blog posts and infographics, but the only way the debate community will change is if we hold their most sacred currency for ransom — ballots.”

After hearing the first team detail the misgendering and abuse they and other transgender debaters often experience in debate, their opponents conceded the round. Instead of demanding to argue the original topic decided by the National Speech and Debate Association, the two teams agreed that the final round of TOC — a tournament that may take a debater hundreds or thousands of hours of preparation to qualify for — was the best place to discuss this issue. The next 45 minutes became a discussion between the judges, debaters and spectators about how to make the debate space more inclusive.

Debate is designed to be self-regulating, a space that allows for discourse not only about the assigned topics but also about the very structure of debate.

“You see students get together and have forums,” Lue said. “We discuss what’s important to us: What do we need to change? What is something that people are having problems within this space?”

An article published by Victory Brief Institutes describes this form of debating — debating about debate — as theory, a newer “progressive” form of argumentation. “The original purpose of theory was to check back against unfair, or ‘abusive,’ arguments or practices in debate. Theory isn’t intended to determine if a rule was broken; rather, it’s an ever-evolving understanding of how debate should function.”

Essentially, if something about the debate round isn’t fair or educational, then debaters are able to use a theory argument instead of, or in addition to, arguing the original topic. This type of progressive argumentation can range from trying to prevent bad debate practices, such as repeated misgendering, or specific debate arguments by targeting underlying assumptions in the round, such as capitalism or the United States’ global dominance inherently being good.

However, this is an imperfect solution. While the freedom to publicly point out flaws in debate gives the event the ability to grow and improve, debaters have also taken advantage of this alternative form of argumentation, using theory to win a round instead of making meaningful changes to debate.

“I think theory in Public Forum debate can be useful, especially when used to further a cause or make something more fair and equitable,” former debater Sierra Howard, ‘19 said.

Howard and her partner used a progressive argument in their senior year against debaters who claimed that giving domestic abuse victims a few thousand dollars a month would enable them to escape their abuser, pointing out the nuances in abuse and calling out their opponents for trivializing the seriousness of abuse.

“It’s tough because sometimes you make things unfair by even using theory arguments because it takes a lot of resources for a team to learn about and successfully use theory. You have to weigh the importance of your theory against the chance you’re edging someone out of a round,” Howard said.

Herman believes that change in the debate space shouldn’t rest solely on the shoulders of high school students but rather needs to start with their coaches. She explains that certain private debate academies or students who hire private coaches don’t necessarily do as much to background check who they hire as other schools do.

“[Coaches] are usually selected for their competitive success, and not necessarily their integrity or their history of working with students or their ability to behave safely and properly with students,” Herman said.

Another avenue for change that has support among the MVLA team is an increased emphasis on judge training. When judges submit ballots, they already see a short disclaimer about being mindful of biases.

“We get what you would call a lottery of judges, and sometimes you just lose the lottery,” Ong said. “It’s really unfortunate because then it becomes less of a debate on skill and more of a debate on if you’re just unlucky with a judge.”

Speech & Debate isn’t the cause of society’s problems, but it does amplify many of them. However, it also uniquely sets up the community to lead the charge against changing many traditional norms of professional speaking and dress. By making a conscious decision not to impose the same outdated standards that have plagued the professional world for years on teenagers, the event can change — not just itself but also the countless students and judges that go through it.

The MVLA team

Despite the misogyny that women face in the greater debate community, the MVLA debate team has worked to overcome those obstacles with a student population and mainly female leadership team.

“[Our team] has been led by women for more than 25 years,” Herman said. “It has a strong culture of women who are empowered and have positions of power [to] take the lead and be an image of success for young women on the team.”

The varsity Public Forum team consisting of all female debaters is one example of the MVLA team breaking through gender disparities and inequalities.

“The [public forum] team is just so wonderful,” Ong said. “We have two amazing varsity public forum leaders and captains who make the space such a welcoming and just friendly environment.”

With the fun and inclusive atmosphere that the leaders and members create within the club that greatly supports female debaters, the MVLA speech and debate practices and tournaments are activities that many look forward to.

“The people you find, the confidence that I got from debating, and when parents are listening to me and believe what I’m saying, is kind of magical,” Maya said.

The team’s new Diversity Equity and Inclusion Committee is working to recruit volunteer debate judges so students don’t have to hire judges themselves, making debate more accessible not just for gender minorities but also for students from low-income backgrounds. Interested volunteers can contact Julie at [email protected] for more information.

Opinion: Debate is a lesson in justice

A running gag between some of the debaters on the MVLA team is that the motto of debate is “life isn’t fair.”

It seems somewhat contradictory. Debate is an activity built on reason and logical arguments. My debate event, Public Forum, basically worships at the altar of pragmatism. Whoever proves their argument provides the most good for the greatest number of people wins.

And for the longest time, I thought debate was as fair as it could possibly be. After all, anyone with access to a computer and the internet could theoretically research and write a case. Everyone gets the same minutes of speaking time, the same amount of preparation and the same chance of winning the coin flip to choose which side to debate. If fairness means impartial treatment, then isn’t having an unbiased judge decide a winner, based on each argument, fair?

It was only later that I realized that while the rules of debate may be fair, people aren’t. People make snap judgments when someone stands behind the podium based on their gender or how they’re dressed or the way their voice sounds. People have expectations for what makes a good speaker, expectations that are far easier for most men to fulfill than women.

I have never been great at emulating that desired measure, even calmness. Inherently, my voice is a bit too high and only rises in pitch when I get excited. I’ve been hyper-aware of my voice and all its deficiencies, but my many attempts to smooth it out or speak lower sound distorted and off-putting. So I’ve spent hours with a pen between my back molars, teaching my tongue to make the correct shapes to deliver crisp and clean words. And for my efforts, I’m still told by my judges to “stay calm” when I’m pressing my opponent with questions, despite him being “lawyer-like” when he spat his own line of questioning at me.

And even after five years of debate, I’m still waiting for when it stops feeling like a punch in the gut when my opponent starts attacking me instead of my arguments. I’ve heard opponents start their speech with, “Judge, don’t listen to their silly arguments” or “Judge, they clearly don’t understand this particular issue.” I’ve been interrupted countless times, only for my opponents to explain to me what my own case is as if I had no idea what I was arguing.

After one particularly egregious case of my opponent trying to fill time by saying that my arguments were “flimsy and foolish” and claiming that I had “misunderstood the entire topic” without actually attacking the logic behind my case, I had enough. During my speech, the first thing I said was that my opponent was using ad hominem attacks instead of interacting with my argument, and that I did not appreciate his comments. After the round, my judge told me he didn’t think my opponent had done anything wrong and asked me to stay on topic.

Judges and opponents like those are a small minority, but their actions seem to have become normalized — but not permanently. It’s idealistic, but I believe that debate has the built-in mechanisms to fix itself. After all, the absolute best part of the activity is putting together countless driven and incredibly stubborn people. With more and more debaters raising awareness of discrimination, there is a slow but sure movement growing.

Pursuing impartiality isn’t working, so let’s aim for something better: actually working to fix the system to offer equal opportunity to debaters of all genders. That’s not fairness, that’s justice.