Shouting Really Loud: Media Under Trump

May 24, 2017

Donald Trump may hate the media, but he’s also its biggest consumer. Per The Atlantic, he watches over five hours of television a day, and tweets about it in real time. In February, networks hiked their ad rates in the DC area, hoping to cash in on their powerful audience of one.

Fittingly, cable TV has started to seem like one long open letter to the president. After Trump shut down CNN’s Jim Acosta, calling him “fake news,” the network effectively ran a full day of coverage to rebut the claim. HBO host John Oliver actually took out ads in the DC area, hoping to teach Trump some new facts about nuclear policy and healthcare.

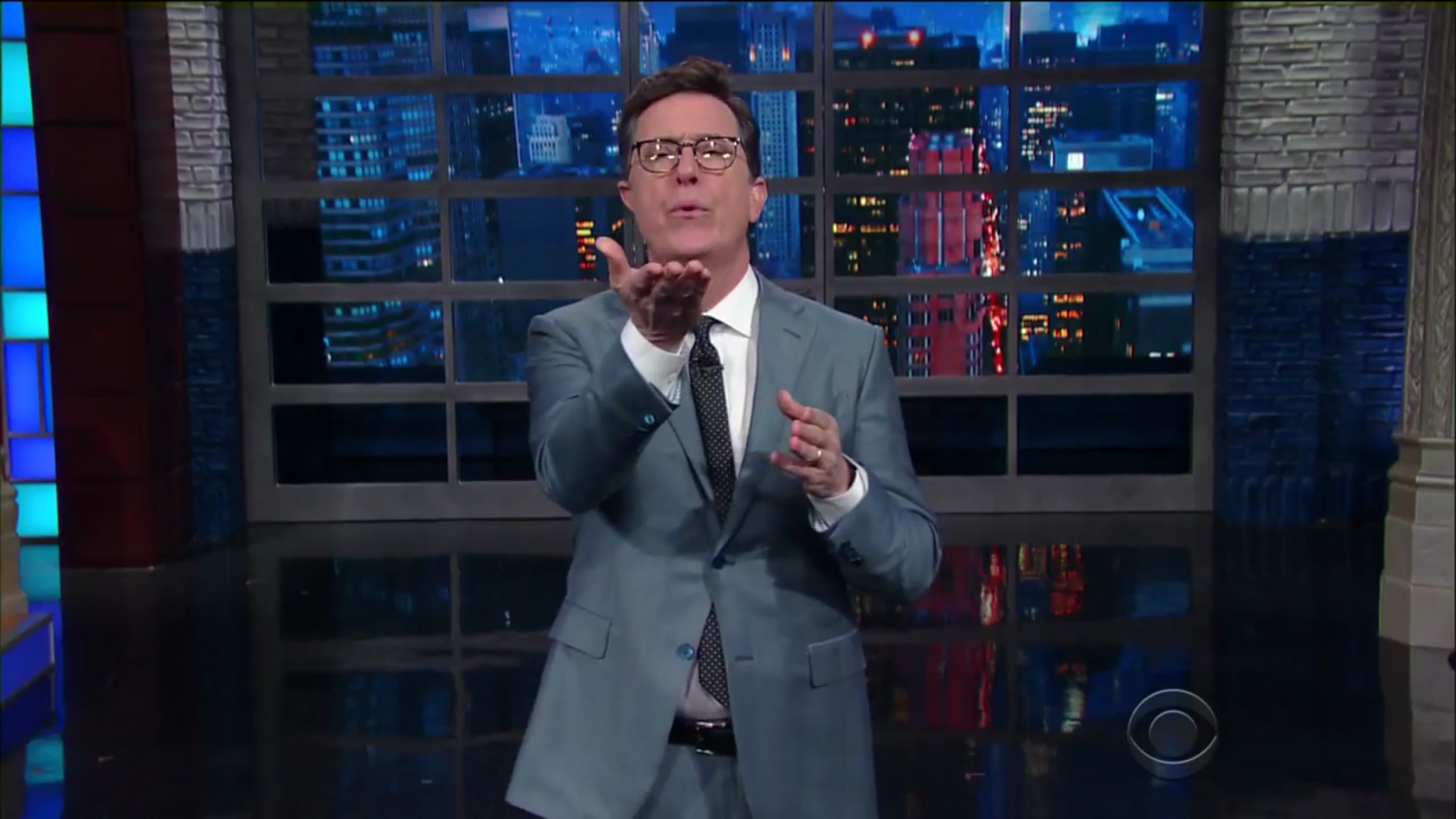

Or take CBS’ Stephen Colbert. After an angry anti-Trump rant that some perceived as homophobic, conservatives briefly pushed #FireColbert on social media, with little success. Trump, in response, derided his show and called him a “no-talent guy” — and Colbert blew him a kiss.

“Mr. Trump, there’s a lot you don’t understand, but I never thought one of those things would be show business,” Colbert said. “Don’t you know I’ve been trying for a year to get you to say my name?”

But while gaining the president, mainstream journalism appears to have lost the public. Just 32% of Americans trust mass media according to Gallup, a historic low. And the fracturing and division of the media landscape has never been more severe.

Trump is a crisis, but he’s also a chance for self-criticism. The public antipathy toward journalism that he highlighted is far older than his campaign, and it won’t be solved by shouting louder. If the media is serious about reaching people across the spectrum, there’s a lot of rethinking to do.

What Went Wrong

It’s easy to feel like Donald Trump singlehandedly killed faith in media, and in some ways he did. The same Gallup report finds that from 2014 to 2015, media trust fell a whopping 8%, almost certainly the result of Trump. There’s never been a president with so much open disdain for the free press.

Yet the problem is a lot deeper and larger than one man. Trust has been falling for decades, from its peak in the 1970s. Americans widely perceive that the media doesn’t do its job the way it used to.

In 2014, Pew Research surveyed ideological conservatives and liberals on their opinions of media outlets. Liberals trusted a disparate variety of news sources — NPR, CNN or the New York Times among them. Conservatives, mostly, trusted Fox News. In terms of the fall in trust, it was almost entirely Republicans. While 32% of them trusted the media in 2014, Trump’s rise cut that figure to 14% by the next year.

So when Trump came along and attacked “liberal” outlets, he wasn’t driving his supporters away from them — just highlighting an existing antipathy. “Liberal” outlets were safe targets because they had never had a following with his base.

Maybe this is why Trump could get away with so many things that the talking heads condemned as beyond the pale. He took a long-term bet that the people who mattered weren’t listening — and disturbingly, he was right.

How to Fix It

The way toward restoring public trust in journalism probably doesn’t pass through the New York Times, NPR or the Associated Press. The big outlets are a little too hamstrung by their institutional connections, their brand is a little too big and, for many Americans, too tainted.

Instead, change has to start local. Most issues become nonpartisan at a small enough scale, which is why it’s a shame that so many local papers have died out or lost their way. But it’s easy to imagine an alternative model of small, web-only publications, focused on covering one community and covering it well. Already, the site DNAInfo.com has built a business model by targeting coverage to specific neighborhoods across New York and Chicago. A revival of hyperlocal news could be revolutionary — reinventing the image of journalism, and maybe even drawing people into engagement with local politics.

From there, the possibilities are endless. It’s easy to imagine how a bottom-up surge in reporting could shake up the industry, as consortia of smaller papers or voluntary information-sharing led the way toward new, inventive ways of covering national stories. Instead of leading with the protests in Ferguson, a hundred local sites could aggregate coverage of police shootings in their town. Instead of an Atlantic reporter finding Trump supporters “in their element,” a citizen-journalist from Akron could ask passersby in the town square.

Or look at ProPublica, which won the first web-only Pulitzer in 2011. They’ve dug into the Trump administration, but without suffering the myopia and all-consuming focus on Trump of other organizations. Unrelated, ongoing coverage of maternity deaths, prosecutorial misconduct or drug marketing gets just as much airtime as the latest administration bungle. This is the simplest, most straightforward version of journalism: finding specific, actionable abuses of power and calling them out. Especially if it emerges organically, this is something people could get behind.

Is this vision of journalism even possible? Considering the degree of business model shift required, maybe not. But either way, journalism has to rethink its structure if it wants to survive. The question posed by Trump — how to win back the public — is an urgent one. With or without him, it’s one that needed asking.