What’s the point of looking at photographs of nature when you can just step outside?

As if we didn’t have our own trees and clouds, photographs of nature are also to be seen everywhere — and, at first glance, the verdant exhibition “Second Nature: Photography in the Age of the Anthropocene” at the Cantor seems to offer more of the same, feeling too familiar to us to be worth a visit.

But “Second Nature” in its gestalt is less a collection of portraits of trees and landscapes, and more a study of the Anthropocene, our period, the proposed geological epoch in which we as humans have been the dominant influence of geological change.

Moving through the exhibition’s four themes added interest, as one can compare the various approaches to nature in our own time. Split into four thematic sections, the exhibition begins with “Reconfiguring Nature,” moves into “Toxic Sublime” and “Inhuman Geographies,” before finally ending on an optimistic note in “Envisioning Tomorrow.”

There was much more variation among the works than I, at least, had expected. The artists’ interests range from color graded photographs, to beautiful cyanotypes, to 3D sculptures, to photographic montages, to heated chromogenic prints.

The exhibition was originally curated by Jessica May and Marshall Price, set in the Nasher Museum. The show was brought to the Cantor by media curator Maggie Dethloff, who saw its relevance for the Bay Area and its entwinement with the region’s technological and ecological narratives.

“We’ve proposed the Anthropocene as a complex web of global relationships, between and amongst capitalism, economics, religion, and agency,” Price said. “Climate change is one part — a very pernicious part — of the story, but it’s not the only part. My hope is that people will walk away with a more complicated understanding of the idea.”

Adverse to the didactic nature of photojournalistic images, May and Price much instead preferred the exhibition to be of artistic nature. The exhibition is special in its almost painting-like ability to take images that we know well (too well, even) and transform them into something artistically beautiful, imbued with figurative meaning.

“It is not just about how we directly impact the landscape, but about how we conceptually approach the landscape — how do we learn the landscape?” Dethloff said. “How do we teach it? What do we think about it? How do we even define this word, ‘Nature’?”

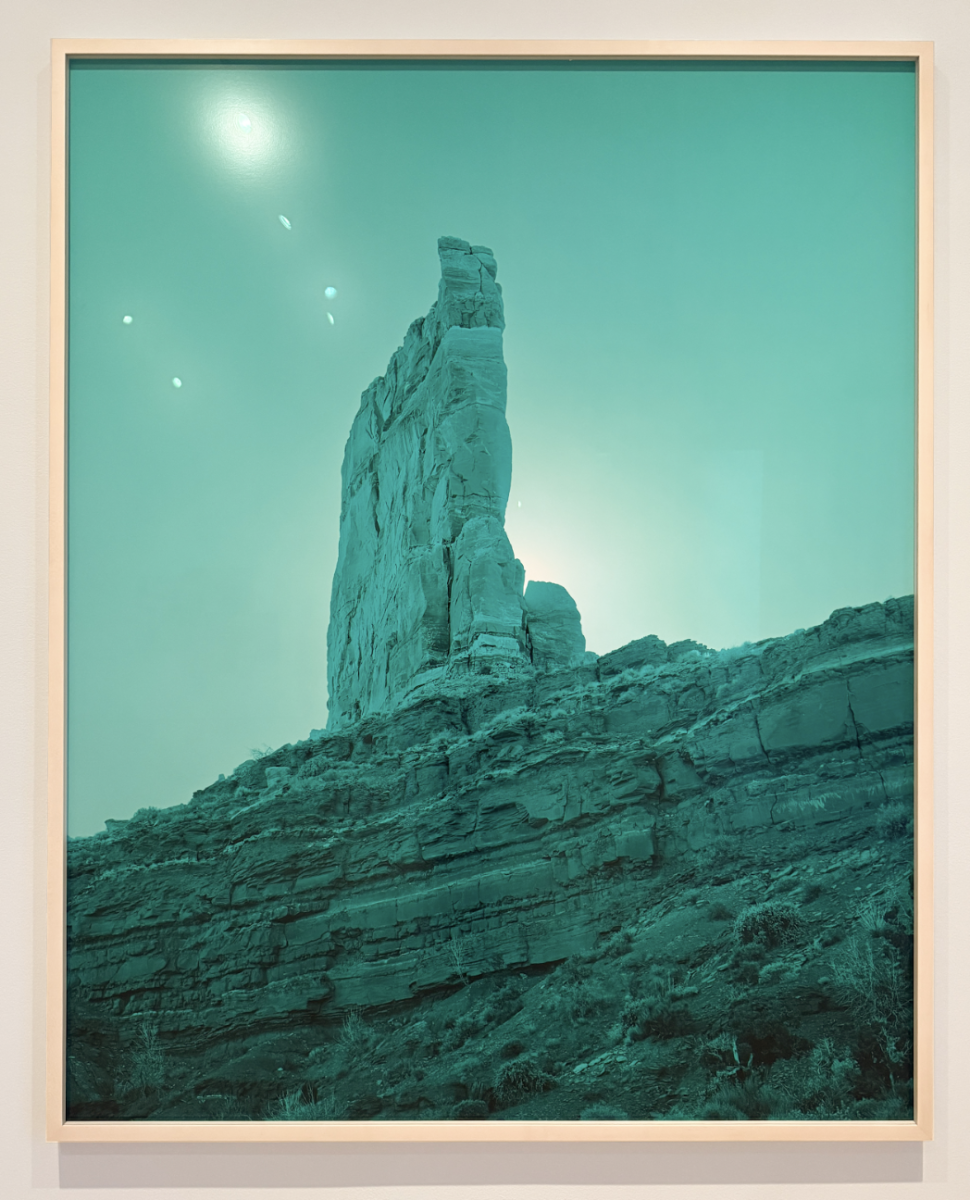

The beautiful “Valley of the Gods” (below) by David Sherry, one of the photographs you see first upon entrance to “Reconfiguring Nature,” does exactly that. Simply through overlaying a bluish hue into the mountaintop, Sherry turns a familiar landscape into something more alien — “queering the landscape,” as Dethloff describes — because the piece is about Sherry’s own experiences feeling like an outsider as a gay man among heterosexual families while hiking.

And Todd Gray’s “Cosmic Blues (Makes Me Wanna Holler)” and João Castilho’s “Morro Vermelho” (below) don’t just alter the colors but also their occupance of space, through “reframing and montage,” overlapping and superimposing many images of various shapes and sizes to create a photographic mesh.

“The exhibition forces you to think,” Price said. “It’s not as obvious — it’s maybe not as accessible as a more conventional work of art. But hopefully it will elicit these questions and encourage the viewer to think about some of the larger questions at play.”

Artists in the section “Toxic Sublime” grapple with the artistic dilemma of aestheticizing ruin — how do we capture terrible destruction in a way that is both authentic and visually interesting?

We can see the question’s implications in the chromogenic print titled “Vatnajökull YCM17” (below) by Matthew Brandt, which looks corrupted, static-like. You see the iridescent reds and purples and teals that make it beautiful, ethereal. With its erratic blobs, colors, and lines, the print gives of the vibe of something literally toxic, visually sublime. To produce the piece, Brandt took an originally conventional photograph of the Vatna glacier in Iceland, and then manipulated the print with fire and heat to create an abstracted, color-graded image.

A standout piece of this section is the multimedia installation “Forbidden Fruit” by Léonard Pongo, replete with translucent draperies, a UV print on plexiglass, and a video installation that suggest a sense of otherworldliness. The installation, in its distilled idealization of nature, represents Central Africa’s landscape as imagined by the colonial mind.

Subsequently, the self-descriptive section “Inhuman Geographies” shows us the human cost of anthropocene environmental damage.

“The whole show is human-centric, in the way that the Anthropocene as a concept is human-centric,” Price said. “We are the drivers of so much of this change. But the third section emphasizes how all of this isn’t a problem for just us. It’s imperative that we address these issues both for ourselves and our non-human but living neighbors.”

For instance, the piece “Between the Mountains and Water No. 51” by Kechun Zhang is a photograph of uncontrolled urban sprawl and smog that comes with it. You’ll see a giant floating pumice stone, and, close-up, realize those little dots at the bottom left are people. Foggy, dystopian, and beautiful, Zhang depicts the landscape and in this case does so without focusing in on the centrality of humans to it.

The final section “Envisioning Tomorrow” is cautiously optimistic, and invites us to imagine futures of restoration and care of the natural world, without minimizing the devastation of climate change.

“As much as it was important to be honest about the devastation in the landscape, I think it is hard for people to try and change things if they feel it’s very hopeless,” Dethloff said. “Having a section at the end to galvanize a little bit of hope and action was really important.”

“Untitled #2” and “Untitled #4” by Gohar Dashti do just that. The two photographs have a more vintage feel, showing the reclamation of nature as plant life seeps through windows and furniture of homes, and as if human architecture is softened by the natural world’s presence.

María Magdalena Campos-Pons’s “Blue Refuge” expresses the “human longing for spring and the stillness of winter.” In its icy blue and floral motifs, a central figure — a woman? — appears swaddled in textiles, with the length of her braid extending outwards, linking her together with specimens of greenery. And her piece is also meta: inspired by the epiphyllum flower — which blooms rarely and unexpectedly — she uses the blossom as a metaphor for her precarious and almost miraculous art-making process.

According to Price, “throughout the exhibition, this story is one of trying to understand and contextualize the environment, and then by the end, galvanizing people to think about things in a different way — even if they’re not going to do something — because that’s step number one.”

And so, this exhibition elects to show us the beauty and fragility of nature — and the anthropocentric side of it all — showing us nature as something beautiful and thoughtful, worth a little more attention and preservation and care.

“Second Nature: Photography in the Age of the Anthropocene” is on view until Sunday, August 3, 2025.

Museum Hours

Monday & Tuesday: CLOSED

Wednesday: 11:00 am – 6:00 pm

Thursday: 11:00 am – 8:00 pm

Friday: 11:00 am – 6:00 pm

Saturday: 10:00 am – 5:00 pm

Sunday: 10:00 am – 5:00 pm