School Tackles Student Well-being

April 27, 2016

Words like “depression” and “stress” have long circulated in local high schools, infiltrating conversations from teens’ lunch tables all the way to the meeting rooms of district board members. This dialogue attempts to address an issue that has only gained recognition in the past decade, prompting a push to promote student wellness in the face of increasing academic expectations.

LAHS’ first changes involved structural remedies, including creating the modified block schedule and encouraging dialogue between parents, students and teachers. They were intended to create a new mindset focused on wellness that allowed more health-centric engagement with the student body.

But since teenagers began to take their own lives in nearby cities, forming suicide clusters at Gunn and Palo Alto High School, LAHS administration has jumpstarted a more urgent discussion. Staff members have begun assembling teams to treat diverse aspects of the issue, ranging from connecting with at-risk students to alleviating stress factors in the classroom.

“There are teens throwing themselves in front of trains in Palo Alto, [and] Palo Alto is not that different from us,” English teacher Margaret Bennett said. “It would be irresponsible to not [ask], can we do more as a school to support students?”

Counseling those at risk

For therapists at the school, addressing student suicide risks, while not routine, is not uncommon. The school identifies students that need attention through self-referrals or referrals from friends, parents, teachers or counselors.

After referrals come conversations to assess students’ wellbeing.

“The suicide assessment is a conversation, and the first thing we want to do is make a connection with the student,” district clinical services coordinator and school therapist Susan Flatmo said. “How’s school? How’s home? Importantly, we tell students [that] it’s about their safety.”

As conversations progress, therapists begin to draw from more resources. They may involve parents, with transparent communication and inclusion of the student.

If necessary, school staff can utilize connections with El Camino Hospital, Stanford Medical Center and the Crisis Stabilization Unit in San Jose for more expansive resources to help students.

“We have something called a warm handoff,” Flatmo said. “If a person needs to go to the hospital, parents are brought in, [and] we’ll have them fill out a release. Going to a hospital can be scary, and we want it to be as good of an experience as it can.”

Toward the end of March, the administration placed support boxes around the campus, where students can fill out a form to refer someone in need of help. Flatmo and the administrators created the boxes as an extension of already available resources, including the team of four therapists, in the hope that students would feel comfortable in anonymity.

“We realized there’s a group of students that did not want to get help because face to face was too much for them,” Principal Wynne Satterwhite said. “It has been very successful, [but] it has taxed our resources, because we look at that three times a day.”

A teacher initiative

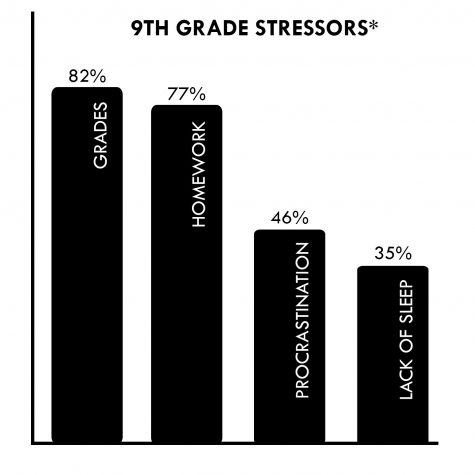

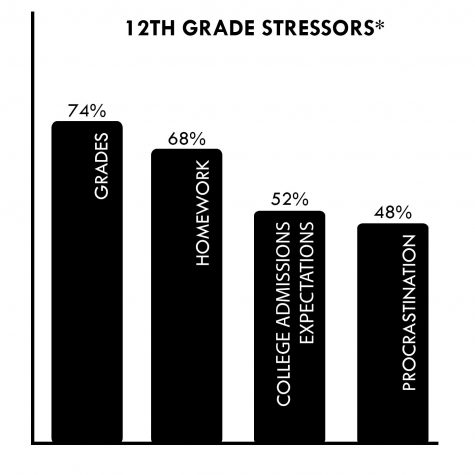

The first step toward helping students is to identify their problems. In February, the school administered a wellness survey to a sample of students, giving administrators and the wellness team an understanding of student priorities.

“The bigger questions were, ‘what is causing you stress, and what would make it less stressful?’” Bennett said. “The school’s been moving in the direction of having data to back up their decisions instead of guessing at what was causing student stress.”

Students labelled grades and homework as their main stressors, which can be mitigated through district policy changes as well as increased teacher awareness of the work assigned.

“[Teachers] should stop once in awhile to ask, ‘How has this helped you, how could it be more efficient?’” senior Stephanie Gee said. “Teachers don’t ask enough whether we think what we’re doing right now is going to help us.”

In the classroom

To confront student stressors in daily classroom routines, a few teachers on the wellness team have turned their attention to environmental wellness. At its core, their belief is that by changing the physical environment of students, the school can affect their well-being throughout the day. Due to a limited budget, teachers settled on one specific change: replacing the furniture.

“We’re in these 1950s buildings, and 1950s desks and chairs,” Bennett said. “Is there more that we can do with our environment to make it more modern or help learning through the environment? If you’re having students sit in chairs all this time, is there a way to make it more ergonomic?”

With this in mind, Bennett and a team of three other teachers across subjects have begun ordering and testing furniture that they believe will boost students’ comfort and mood in addition to opening new opportunities for classroom spaces and group work. They are focusing on finding desks that are mobile and flexible, in which students can move around and adapt furniture to their ergonomic needs.

“We’re trying to make it so that it’s not a one-size fits all, but it’s adjustable, movable and fluid,” history teacher Kelly Coble said. “Desks and chairs that you can move so that physically you’re comfortable, but also emotionally and mentally, you’re not just rigid in one desk everyday.”

P.E. teacher Kiernan Raffo is pursuing these goals through a different approach: a wellness unit for freshman P.E. Currently, Raffo runs a weekly program taught by professional trainers in which P.E. students observe the benefits of breathing, flexibility and yoga exercises.

“The wellness people have done a good job of creating different circumstances for [students] so that they can relate,” Raffo said. “So they can see that it’s much bigger than just being in a classroom, whether it’s homework or you’re in a fight with your family.”

This type of learning is designed to occur in classrooms as well, whether teachers choose to implement the P.E. classes’ exercises or take different routes. Flatmo described an occasion in which a chemistry teacher told her class that she was going to show them a “kitty video” before a test.

“As expected, the whole class groaned,” Flatmo said. “But she put it on, and they watched it for a few minutes. People chuckled, in spite of themselves. And they took the test… The teacher posted the results… and students did better than expected.”

The students took the next test without the video, and their results dropped back to normal. While the experiment holds no scientific bearing, Flatmo argues it’s an example of an in-class method to relieve stress.

“The next time she said, ‘Kitty video, or no kitty video?’” Flatmo said. “They all said, ‘Kitty video!’ That’s a good example of teachers working with kids and giving them ways to relax before they take a test.”

Ultimately, the new path for the school focuses on alleviating broader stresses and reducing the load on students’ shoulders through varied approaches.

“The kids are multifaceted, [and] the schools are multifaceted,” Bennett said. “For some people, it’s their family. For other people, it’s the school load. For other people, it’s emotional issues… We tried a lot of different ways to get at it, and hopefully it’ll help all students in some way.”

A changing culture

As Bennett, administrators and the therapy department pushed for greater thought and discussion on mental health, they witnessed a change in attitude. Staff members became more receptive and concerned about student issues.

“It seems like now, when you say things like ‘stress’ and ‘mindfulness,’ you don’t get, ‘This is not even an issue,’” Bennett said. “You get, ‘Oh, what do you think would be [a] solution?’”

Satterwhite believes that this will empower student initiative in powerful ways.

“As a principal, you can say lots of things, but it’s hard to make those things happen without support,” Satterwhite said. “It’s trying to find buy-in from staff, and students and parents, so when you run into walls they can say, ‘No, this wall isn’t big enough, let’s take it down.’”