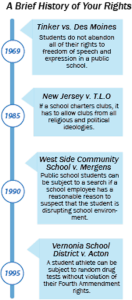

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]The California constitution guarantees the fundamental right to a public education. But this guarantee is only the first in a long line of significant constitutional rights that public school students in California have. Several Supreme Court cases have extended many of those constitutional rights to public school students, though while at school, public school students have different rights from the general public. Unlike Tinker v. Des Moines (1969), some Supreme Court cases have decided that other rights are left behind at the school gate.

Most of this is due to a concept known as “in loco parentis,” or a school’s right to act in the place of a student’s parent to keep the school environment safe and non-distracting for others. Most laws and court decisions about student rights fall into two main categories: those that deal with student privacy and those that deal with freedom of speech and expression.

This article specifically talks about cases that concern the rights of public school students, and is not meant to be a comprehensive list of rights but more of a sampling of some of the most important and controversial ones. Although most of the rights discussed in this article involve national Supreme Court cases, readers should recognize that California has enacted legislation that generally provides its public school students more rights than students in the rest of the nation.

Though plenty of legislation exists in order to protect student rights, some of these laws can be impinged upon if it means creating a “safe and non-distracting” environment for others. This is something that comes into play with one of the two classes of right infractions we will discuss.

What Are a Student’s Privacy Rights?

Two Supreme Court cases in particular set the tone for addressing a student’s right to privacy: New Jersey v. T.L.O (1985) and Vernonia School District v. Acton (1995). New Jersey v. T.L.O concerned a student at a New Jersey school who sued when the school searched her backpack because they suspected she had possession of marijuana. According to the student, the search was not authorized and it amounted to a violation of her right against unreasonable search and seizure. The Supreme Court ruled in favor of the school district, saying that students’ rights can be overridden if the school has reasonable suspicion to think that the student will disrupt school environment. In T.L.O’s case, a teacher had previously caught her with marijuana, then later decided to search her again.

An incident similar to this happened at LAHS in 2006. Then-sophomore Cesar Enciso was arrested and made to take a drug test after a teacher suspected he was under the influence of marijuana. Enciso passed the drug test; authorities said that was because the drug test wasn’t comprehensive. Enciso later sued for an infraction of his right to privacy. The case’s jury sided with the school.

An incident similar to this happened at LAHS in 2006. Then-sophomore Cesar Enciso was arrested and made to take a drug test after a teacher suspected he was under the influence of marijuana. Enciso passed the drug test; authorities said that was because the drug test wasn’t comprehensive. Enciso later sued for an infraction of his right to privacy. The case’s jury sided with the school.

Consistently, California courts have given school administrations a lot of jurisdiction with regards to student searches. That being said, it is safe for a student to assume that, while their belongings are not entirely free rein for schools to search, they should not assume that their privacy is absolute, particularly with regards to items that could be considered dangerous or disruptive.

Vernonia School District v. Acton concerned a high school athlete who protested the Vernonia school district’s mandatory drug testing. The student claimed that the random testing was a violation of his right against unreasonable search and seizure. The court ruled in favor of the district, saying that during school hours, public schools have greater control over their students, something that depends largely on how the school sees fit to deal with a situation.

What about Freedom of Speech?

Freedom of speech and expression is the right that has garnered perhaps the most attention. Tinker vs. Des Moines was a landmark case in deciding what rights students have at school; the court decided that students’ right to freedom of speech cannot be suppressed unless the school has a justifiable reason to believe that a student’s actions would “materially and substantially interfere” with school function. Protests against dress codes are widespread; many schools say that they exist to keep the school environment “non-distracting,” an expression that doesn’t sit well with many students. According to them, dress codes create a double standard between male and female students.

Another instance of freedom of expression comes with a student’s ability to express their religion while at school. There have been court cases concerned with religious activity in public schools, such as Santa Fe Independent School District v. Jane Doe, a case that found school-led prayers before basketball games unconstitutional. Yet, an American public school cannot outright forbid religious and political activity to take place on its grounds. In the court case West Side Community School v. Mergens, the Supreme Court ruled that if a school allows clubs to be chartered, they have to allow clubs of all religions and political ideologies.

When a school has government-given permission to ban an activity, it is usually because the activity has been deemed to be creating an environment that is “unsafe and distracting” for the majority of the students. Such is the basis for many of the restrictions that students have at a public school; in the eyes of the government, they’re meant to protect the students and the environment in which they learn.