There is no way for anyone to be 100 percent “genuine” anything. However, not all of us choose to write about it.

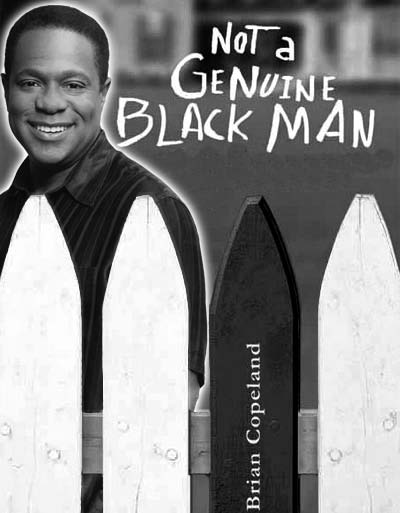

But Brian Copeland, who is the keynote speaker for the 25th annual Writer’s Week, wrote “Not a Genuine Black Man,” a deeply provocative piece that speaks of how our environment shapes our identity.

In the 2006 book, Copeland reconsiders his childhood as the only black kid in a “99.99 percent” white neighborhood. He since tried to forget growing up amidst racism in San Leandro, California, but a letter accusing Copeland of being “not a genuine black man” forced him to think again.

Like many students experienced in the school’s Cultural Proficiency sessions earlier this year, Copeland struggles to deal with others’ perceptions of himself.

After moving from Oakland to the city of San Leandro in the summer of 1972, Copeland was arrested several times because of his race: Once, he was only carrying a baseball bat to find a park.

Back when San Leandro was America’s so-called “most racist city,” the white neighbors wanted to keep their city white. Copeland endured bullying in his Catholic school (where the patron saint was ironically African-American) and apartment complex, fighting with his father to become the “man” of the house and descending into depression.

The chapters of the book jump between the San Leandro of then and the San Leandro of now. Copeland writes informally, and at times his style can lead to unclarity, especially in his description of a badly-attempted suicide later on in life. Though the jokes he makes are generally funny (although not laugh-out-loud), less humor would make reading more straightforward during the more serious and potentially confusing parts of the book.

However, the same informality and an overprotective grandmother give the book a sense of reality that no other type of writing can accomplish. He jokes about his attempted suicide: “In the state of California, it’s illegal to commit suicide! What’s the penalty? Death?”

Copeland tends to glaze over some important moments in his life that the reader is still intrigued about—namely, his mother’s death and his young adult years. We see the Copeland of today and the Copeland of 20 years ago, though readers still may not fully understand Copeland’s experience after reading the book.

The book offers a fresh perspective on diversity, similar to the conversations the school has been trying to have of late. Though by no means a vicarious experience, students will gain a perspective differing (and also entertaining) from theirs by reading Copeland’s work.

While there may not be a rock-solid plot, the outcome of Copeland’s life is certainly interesting enough to keep anyone looking forward to flipping the page.

Though the book is also a one-man stage show, there is something comical about the book “Not a Genuine Black Man” a reader can’t find anywhere in any other method of communication. After all, truth is hidden in humor, and Copeland has found the happy medium—in accepting his skin color and the perceptions that come with it. The end of the book is happily genuine as Copeland finds the “true” black experience hidden in his past and open in his future.