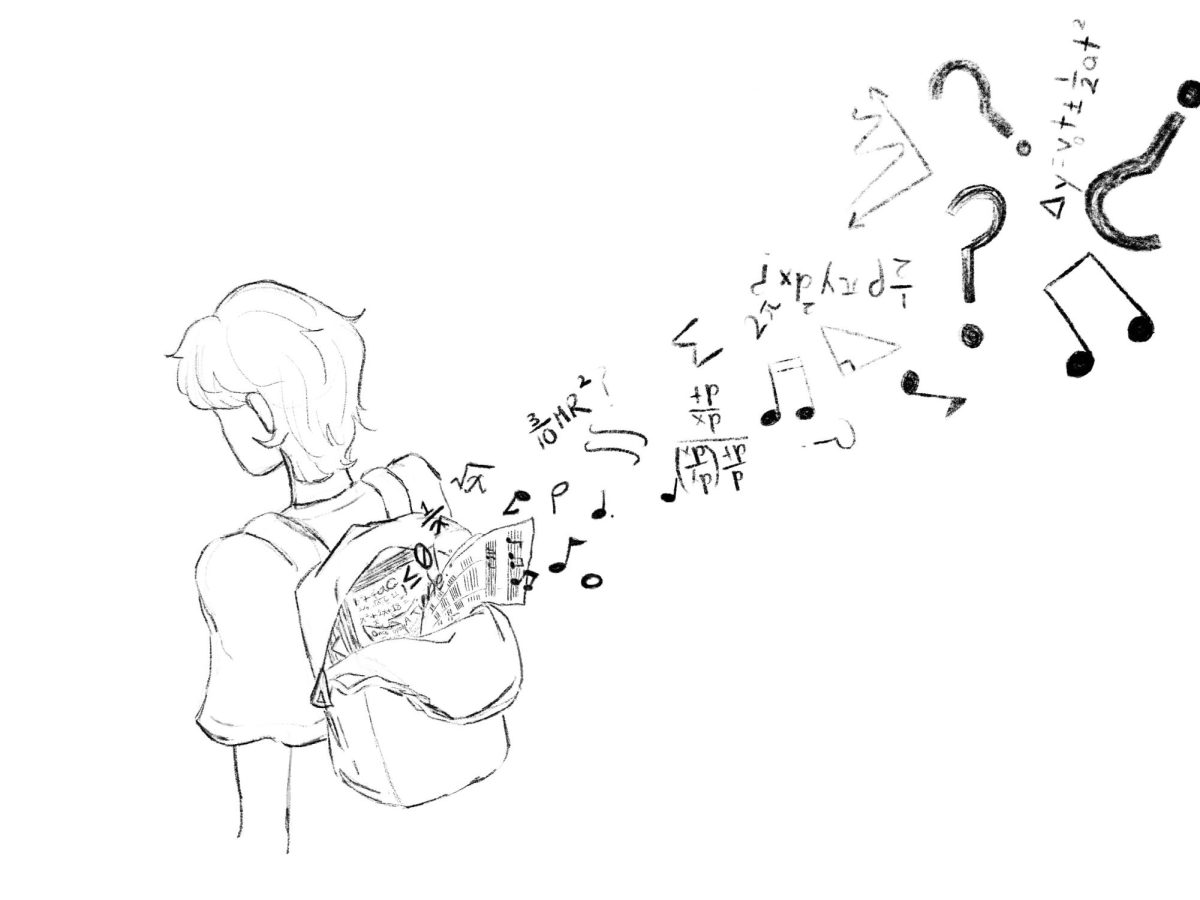

I was in middle school when I learned the difference between a “good” student and a “capable” student. A “good” student underlined their thesis in the introduction paragraph, memorized geometric proofs, and strictly followed the grading criteria. A “capable” student might ask too many “disruptive” questions, wander too far beyond the rubric, and care more about the problem than the points.

I wanted to be both, but school results made it clear which was more important.

By high school, I, once somewhere between “capable” and “good,” had settled into “good”: good enough to get As, good enough to dedicate all my time to extracurriculars I swore — without a doubt — had been my life’s passion since age five. It’s not that I didn’t stop wondering about the big questions; I just didn’t have the time or motivation to resolve them. The system rewards efficiency, so we all became efficient. But in the process, I felt something was lost.

There has been much criticism of our education system for failing to evolve with the times, and creativity is at the center of this discussion. Because we live in an era that increasingly values innovation, schools are often accused of stifling the very skills that drive progress. In “How the Current Formal Education System Cripples Creativity and Harms Society,” Angel Kobelo argues that formula schooling “kills creativity and fosters low self-esteem,” pushing students to conform to pre-selected knowledge rather than to question the limits. While this piece takes a hard stance, it captures the disillusionment many students feel when faced with the consequences of their school performance.

But “creativity” itself is not a single universal trait. Some associate it with imagination, while others define it as the ability to solve problems using logic. I’m not here to question whether schools kill creativity, but rather, what kind of creativity schools seem to value — considerate of their intentions.

Our education system prioritizes what can be measured, then eventually compared. For instance, test scores, GPAs, rankings, all hold more weight than qualities such as intellectual curiosity or creativity — attributes that are near impossible to assess. As a result of this, students are indirectly conditioned to focus on “tangible” outcomes as opposed to the process of learning itself.

Ironically, our education system also sells itself as a place for intellectual growth, a system designed to “foster critical thinking and discovery!” But in reality, it often functions as an optimization problem: How much knowledge can students recall and apply in the shortest amount of time? That’s why, for many, grades become the currency of success — they’re the most tangible measure of achievement.

And like it or not, grades do matter if you personally see them as a path to more opportunities. It’s not irrational to prioritize them. The problem is just that school conflates good grades with a deep understanding of subjects, when grades often measure something completely different: a student’s ability to game the system, and to perform competently rather than engage deeply with the material and beyond.

I’ve noticed this rigidity plays out differently in STEM and humanities. In English, I used to follow a cookie cutter structure of five paragraphs and thesis statements that listed summaries of each of the three topic sentences (which sounds clunky and disengaging). Over time, I was given more flexibility. Only the delivery of a compelling argument truly mattered. As long as my line of reasoning made sense, I was free to play around with the essay structure.

STEM doesn’t allow for that in the same way during regular instruction. The right answer matters, as it should, but in the rush to cover material and prepare for tests, what often gets lost is the personal curiosity that makes learning meaningful. Don’t get me wrong, many STEM teachers are deeply passionate and happy to explore ideas beyond the textbook, but that kind of learning often happens outside of structured class time, not within it.

That’s not to say STEM should mirror how English is taught — the disciplines are fundamentally different. But both can suffer when education shifts too far toward outcomes over exploration. Just as English becomes formulaic when given a rigid essay structure and word limit, STEM loses its spark when there’s no questioning beyond the equations and final answers. English, at least, tends to come with “training wheels” that eventually give way to more flexibility. STEM courses don’t offer that same progression. The opportunity to think beyond the surface is always there, but it’s often left entirely to the student to seek it out. And in rigorous classes — much like the kind we have at Los Altos High School — students are so focused on keeping up that there’s little willpower to chase that curiosity.

Some argue that schools don’t just favor critical thinking over creativity. But the truth is that schools do try to inspire creativity. They introduce project-based learning, have the occasional open-ended assignment, and even offer electives in terms of art and music. However, these remain exceptions, not the rule. The dominant system is still structured in a way that even when creativity is encouraged, it’s within the limits of what can be assessed. And that’s understandable — grading needs to be fair, and creativity is hard to measure. Schools rely on structure, and students, in turn, focus on what earns them results. It’s a cycle that reinforces itself even when the school system has the best of intentions.

Even with these intentions, some of the world’s most innovative minds weren’t the best students, because they saw beyond the system. Albert Einstein, a notoriously indifferent student, once said: “Education is what remains after one has forgotten what one has learned in school.” Though he excelled in math and physics from a young age, much of his most meaningful learning came from following his own curiosity instead of sticking rigidly to a curriculum. Thomas Edison, though a more controversial figure, was expelled from school for being “addled” and went on to become one of the most prominent industrial figures of his time, largely through self-directed experimentation. Their brilliance didn’t come from following the traditional path; if anything, school tried to morph them into something smaller and more predictable.

And while most of us aren’t Einstein or Edison, I can’t help but wonder how much more I would have learned had I spent less time trying to be the “perfect student,” and more time letting curiosity guide me.

I could end this piece with a hopeful note — a call for schools to change and finally embrace creativity to its fullest. Truth be told, that probably won’t happen anytime soon, because creativity is hard to quantify. The system is built the way it is for a reason: it’s pragmatic. It prepares students for a world that also values the results over the process.

So no, I don’t have a perfect solution, and maybe there isn’t one. Maybe schools have to operate this way, and more often than not, creativity will need to be sought out beyond the curriculum. But it’s still worth talking about. Because while I’ve learned to adhere to the rules, I haven’t stopped questioning them.