Meaningful Mediums: What are the best mediums to convey the message of political art?

September 27, 2017

On a white wall in the Whitney Museum hangs a painting of protesters marching through a street waving blank flags and holding blank signs. A few blocks down, a giant poop emoji with Donald Trump’s face is plastered on the walls of New York City.

Both pieces serve to convey a message. Both can be interpreted as some form of political art.

“Arts and politics go hand-in-hand,” artist senior Monica Badea said. “You can look through the times, and the art is always persuaded by what’s happening.”

Artists like Frohawk Two Feathers believe all their art is inherently political, as it comes from their experiences and identity.

“When you are a person of color it’s almost unavoidable [for] your artwork to be political,” Two Feathers said. “If you are making any artwork about yourself and your situation, it should reflect how you live. I didn’t go out to make any particular statement, but the statement was made by my life.”

Through political art, artists aim to make politics more accessible to their viewers to encourage them to change their perception of politics. But because art itself is often inaccessible, artists have begun to seek new mediums through which they can better convey their messages.

Today, artists are challenging the definitions of both the “politics” and “art” in political art. Art is no longer solely classified as just paintings on a wall; politics no longer lies solely within the borders of Washington D.C.

“[Art] is not just walking into a white cube and looking at pictures that are hung,” visual artist and Iranian activist Ala Ebtekar said. “It’s those everyday interactions or things we may encounter that might be art.”

For some artists, political art does not just provide answers to ideas but provokes questions and promote discussion. They treat art as a criticism of the status quo.

“You would hope that somebody would look at [art] and consider it and have it be a part of them, maybe expanding their modes of thinking on a subject,” artist Adam Feibelman said. “I don’t think that art is necessarily capable of changing someone’s mind, but maybe it’s a speed bump in their road.”

Instead of a traditional painting, Ebtekar facilitated the creation of a collaborative piece from street artists Mike Bam of Oakland and Ghalamdar of Iran. On a wall on Third Street in Oakland, Ghalamdar’s black and white Persian calligraphy harmonizes with Bam’s colorful, free-flowing strokes. Ebtekar commissioned the piece to display the intersection of the two artists — evident in their work — and hopes the piece will create empathy between their two cultures.

This past May, The Luggage Store Gallery hosted a gallery entitled “Welcome to the Left Coast,” to which Ebtekar submitted a painting. Far from the traditional “white cube” showroom Ebtekar describes, The Luggage Store Gallery has a reputation among artists for celebrating experimental approaches to art; one exhibition features a combination of rap, visual art and cooking, and another features an installation of hundreds of wooden, hand-built meditation benches.

In the gallery, Ebtekar’s painting hung alongside a letter folded into an envelope on a shelf. To read the letter, viewers had to take it down from its shelf and remove it from its envelope. Inside, artist Alicia Escott wrote from the future about topics such as the turmoil of the current political climate addressed to the then-extinct coral reefs.

This letter is an installation in Escott’s long-standing project, consisting of love letters to species that have gone extinct. In these letters, she tells the species everything they have missed since they “left her.” Through this interactive medium, Escott hopes to allow viewers to enter the work and have a dialogue with and around it.

“All of those letters are very much for people to have intimate experiences with, because I felt like when you go to gallery openings, everyone’s just drinking wine and saying hi to their friends,” Escott said. “I couldn’t access the audience that way.”

In their mission to create change, Ebtekar and Escott have found that sometimes taking the “politics” out of political art is the best way for their message to come across.

“Different times, different bodies of work that I’ve made, some of them have been political and some of them have not,” Ebtekar said. “Even in the ones that aren’t, there’s this genuine interest in impacting the world for the positive.”

They find that many times partisanship can impede the presentation of an artist’s message.

“In the past I’ve done a lot of partisan artwork, but I’m actively trying to make it less political in order to make more of a point,” Feibelman said.

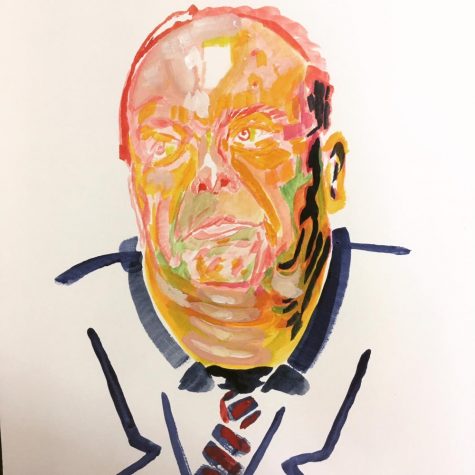

Feibelman’s political art explores aspects of politics beyond those relating solely to Democrats and Republicans. For instance, he is currently working on a painting depicting the opioid epidemic. The painting features the home of Purdue Pharma’s CEO with a heroin addict in his bed. The CEO decided to lie to doctors and say that opioids are not addictive so the company could develop pain killers hurting consumers.

Feibelman and other artists hope to highlight political issues beyond parties such as drug epidemics or climate change, while reminding Americans that partisanship is not the sole focus of politics.

“Rather than having a right or left political debate, I wanted to talk about people who are pulling the string actively to make things worse,” Feibelman said.

The defining features of political art, whether the piece is about Donald Trump or the environment, are hard to pinpoint. But for Ebtekar, the definition doesn’t matter. He believes in the power of art to transform the ways people interact with the world.

“Art can save us in many ways,” Ebtekar said. “If you’re able to have that paradigm shift in what art is, then you could start saying what it could be, and I think it’s those types of experiences that can allow for better understanding of the world and a genuine kind of empathy for one another.”