Thirty-five seniors squeeze into Microeconomics AP, giving new meaning to the phrase “cram session.” They’re discussing the economic recession. The irony isn’t lost.

“In the last 2 years, my average Econ class size has gone up from 25 to 35. Every single seat is full,” social studies teacher Robert Freeman said. “Is the quality of the education the same? No.”

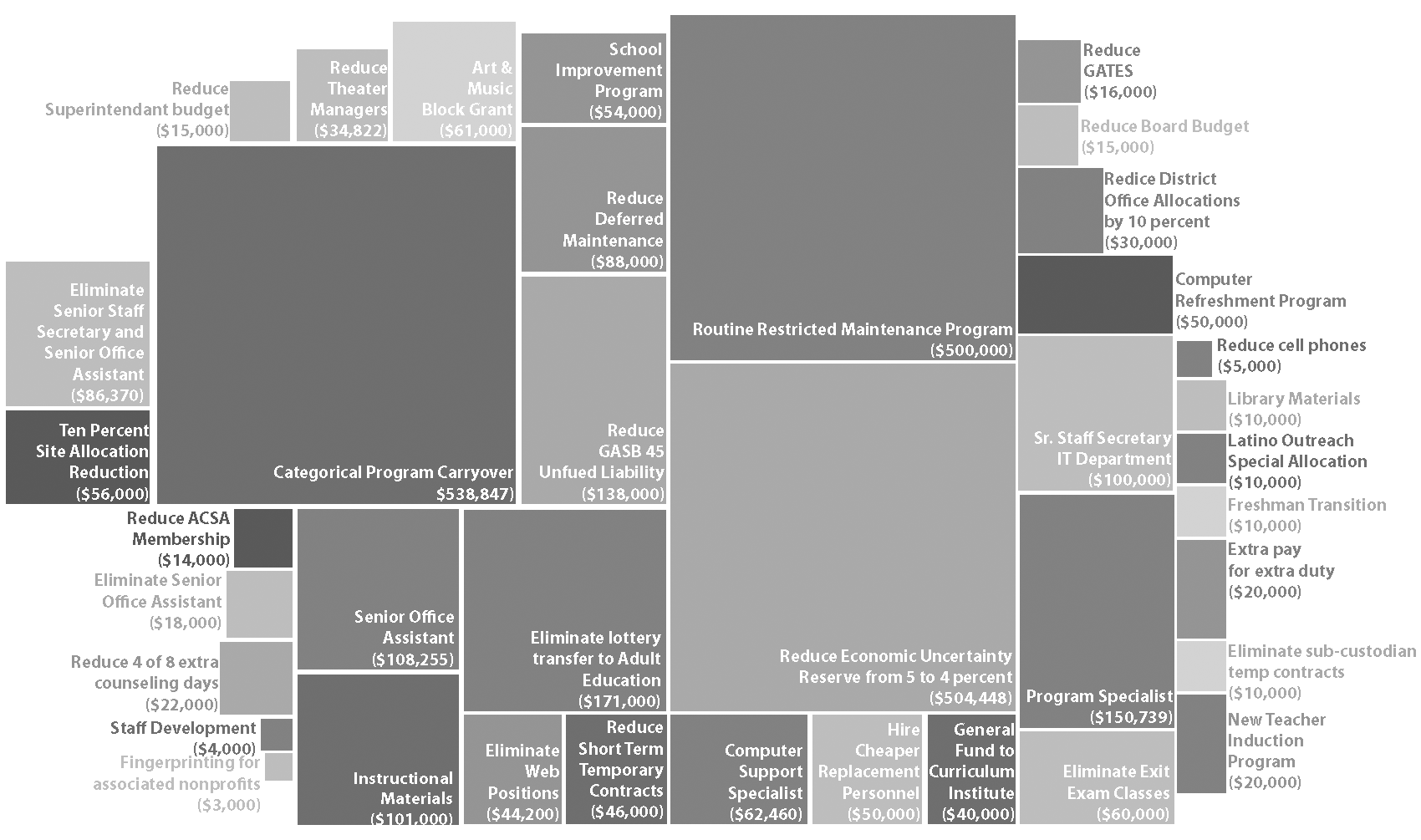

Freeman’s class, like others throughout the school, is a grim reflection of the financial reality of California’s public education. It’s not getting better: This summer the district Board of Trustees pulled the belt a bit tighter—$3,275,141 tighter, to be exact.

“Obviously, when you cut $3.2 million out of a budget it’s somehow going to affect students,” Superintendent Dr. Barry Groves said. “Everything will affect them some way.”

Indeed, students, classrooms and teachers were all affected by the cuts, but the district should be commended for making the most of the situation.

There were casualties and bumps and bruises, but what could have been a disaster for the students and their education instead came through with the classrooms intact. The district’s goal was “to try to keep the cuts as far away from the classroom as possible,” according to Associate Superintendent of Business Joe White, and it shows.

One such way the district has kept the cuts “away from the classroom” is by essentially finding all of the district’s loose change. Numerous one-time programs don’t use up their entire initial grants; the unused money then just sits in an account.

“Let’s say your parents give you $100 to spend, but you only spend $95,” Groves said. “At the end of that account, you have $5. So we swept all the money from the accounts that wasn’t spent.”

And by essentially turning over all sofa cushions to find the coins that fell through, the district saved $538,847. That’s not just petty spending money.

The district then saved another half million by forgoing the Routine Restricted Maintenance Program, the annual summertime general maintenance. Rather than “paint, fix up the school, put up new roofs,” according to Groves, the district decided to hold off on maintenance for a year.

These cuts mean the walls of the school may look a bit lackluster, and teachers might need to smack the appliances to get them working. But they saved the district $500 thousand—money which would have otherwise come out of our textbooks, teachers and supplies.

These two cuts alone covered a third of the total reduction.

Budget cuts are never an easy burden, but the district—by keeping the students far from the cuts—makes the $3.2 million that much easier to bear. We the students shouldn’t be happy, but we should at the very least be thankful—because our district is wading in shallows, whereas districts across the state are neck-deep and treading water, waiting for an unlikely life raft.

“The lack of funding for education is a tragedy,” Associate Superintendent Steve Hope said. “In some places … they’re not getting new textbooks. Class sizes are getting significantly bigger; they’re getting 35, 40 people in a classroom.”

As Hope explains, public schools in California receive the majority of their funding from property taxes, and the state subsidizes the difference. But the recent statewide budget cuts slashed this subsidy, forcing many to cut jazz band or cram 40 students into a sweltering portable on the fringes of campus.

The school district lost $3.2 million, but it has managed to escape such a fate; we have yet to have to say goodbye to a loved history teacher or to field hockey, because of the roughly 1000 school districts in California, MVLA is of the privileged 100 which can support itself with property taxes alone, according to Hope.

“The state, in the most simplistic terms, calculates what the revenue limit is for that school … so there’s a formula that does that,” Hope said. “In our district, being a locally funded district … property taxes come in substantially higher and give us more money per student than that formula would give us.”

But then why bother with the budget cuts at all? If we can stay afloat, especially in the economic recession, why cut $3.2 million? Because in the end, we are not the only district in this state, and we’d be insensitive—to put it nicely—to refurbish a track or purchase new technology while others are slashing into their core.

The $3.2 million, then, was “to do our part.”

“These other 900 districts are getting reduction that we’re not getting, and that doesn’t seem to be fair,” Hope said. “So we said to the state, ‘We need to

give our fair share also, so we will give back as much money as these other districts are being cut.’”

MVLA can survive this year even with a slashed budget; others might not be so lucky. So should we have cut our budget?

Most definitely.

But at whom should we point fingers? After all, $3.2 million isn’t just an accounting blip from rounding errors—someone somewhere made a mistake.

Hope explains the cause of the budget cuts.

“So you have two things happening: you have the State Takeaway and you have less property taxes coming in, which means there’s a hole in the budget,” Hope said. “We’re spending more than we’re taking in, so we have to make cuts to take down the budget.”

The State Takeaway was a conscientious effort by the district to help out fellow schools. The declining property taxes, however, stem from larger, economic trends.

The economic turbulence reversed the trend of property value in the cities of Mountain View and Los Altos, which saw a steady growth in property values in recent years. Without the rising revenue from taxes on rising property values, the district will have to find new sources of income to pay for the increasing cost of living.

“One of the critical pieces of funding for us is: How much does the property tax base grow in this district from year to year?” Hope said. “Because that growth is what helps us pay for new things, increase the budget, pay for increased health care cost for insurance for the staff.”

But the solution isn’t as easy as waiting for the economic turnaround; political deadlock in Sacramento casts a shadow of uncertainty on the already timid economy. Already, the state budget is months overdue on its June 15 deadline, and that’s plenty of reason for alarm. Without a formal budget from Sacramento, the district has to ballpark its running budget for the year. Undershoot, and students are cheated out of a quality education. Overshoot, and the rug can be pulled from under our feet at the last minute.

“We have tried to anticipate the downside so that we can avoid reactionary budget cuts,” White said. “It’s huge. When you have to make drastic budget cuts mid-year, then there could be impacts because you haven’t had time to thoughtfully determine what would be the best approach.”

In the midst of all this uncertainty, though, one thing remains constant: The economy needs to turn around, and Sacramento’s deadlock needs to be broken.

Because if trends continue the way they are, more and more districts will see their funding runs dry, and then it will only be a matter of time before MVLA needs to make the sweeping changes everyone dreads.

“Can we make it through another two years without making major reductions?” Hope said. “I can’t give you the answer to that—I don’t know what the answer is. I don’t know what the economy is going to do or how long we can make it last.”

Already, the district is tapping into its rainy day funds. As part of its annual budget, the district sets aside five percent as an Economic Uncertainty Reserve fund. However, in order to generate the $3.2 million, the district lowered that amount to 4 percent, producing over half a million dollars, but pushing the schools and students ever closer to the brink.

Although pulling from the funds was necessary, it’s an uneasy reflection of our uneasy times.

“The board wants to go back to five percent,” Groves said. “But they need to wait until the economic climate is better so they can gather some dollars and put it back.”

Because the fact is that if the funding dries up, no amount of frugality can produce the money necessary to guarantee a quality education.

Solutions might work temporarily—like the current budget reductions—but we’ll eventually sweep up all the spare change there is, and the walls will eventually need to be repainted.

If the economic crisis doesn’t turn around soon, the best that we can do is keep tapping into the rainy day funds, and hope that the weather clears up tomorrow.