‘Make or Be Made:’ The Growth of New Media Lit

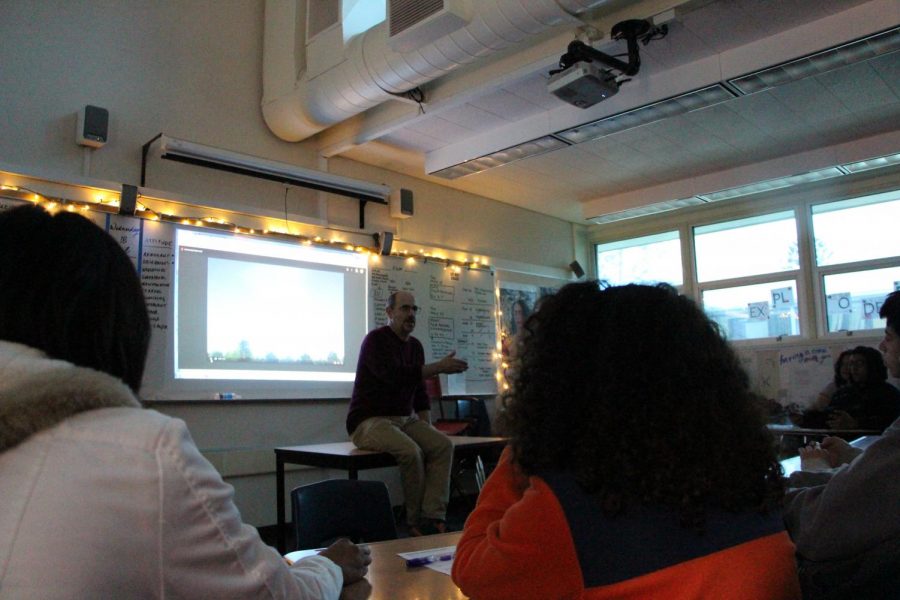

New Media Literature teacher Robert Barker explains the importance of critical media literacy skills in front of his class. This year, the class had a shift in their structure while trying to maintain their motto, “make or be made.”

April 24, 2018

In all caps, “PARKLAND FLORIDA SHOOTING,” is written in black marker and boxed in the dead center of the whiteboard. From it spouts a blue web of intersecting lines, boxed words — an exchange of ideas, a classroom brimming with energy, hands stretched to the ceiling. By the end of the discussion, the students have brainstormed around 40 different angles that a student could approach, and the entire whiteboard is black and blue.

This is New Media Literacy (NML), a broadcast journalism class that’s been around for a little less than two years. The Parkland shooting brainstorm, like a lot of what NML does, is based on the constructivist “sandbox” theory, the pedagogical project-based learning method: teachers provide students what what they need — equipment, resources, a mission and goal — and the students are “thrown” into the sandbox with minimal guidance along the way and help each other out.

This metaphorical throwing-kids-into-the-sandbox means class time devoted to working on videos as well as choosing what content to create. Yet, this independence often leaves the students failing to meet the deadline or unable to come up with an independent project idea. A main struggle NML has is rooted in how they’ve created their constructivist flow — students are unused to this newfound independence.

“Project-based learning involves growing pains,” Barker said. “Our school culture could do a better job with creating an environment where students need to do more of their own time management and real-world project-based work… There’s a sense of ‘I’ll wait to be told what I’m supposed to do’ even though you’re getting the message, ‘I want you to go figure it out, and it’s okay if it’s messy, it’s okay if you make a lot of mistakes.’”

That’s not to say that the sandbox idea hasn’t produced results. Though NML is only in its second year, the class is already taking on longer-length features like covering the DACA protest, completing projects for administrators like STEM week features or a promotional for a class and creating announcements every other week.

But like every new class, NML is still testing the water, and the students found themselves inundated with the barrage of new projects this year.

“I think we all got crushed under the weight of all of these competing expectations,” Barker said. “We’ve struggled to reach the same quality level we met last year with certain projects and we’ve definitely struggled to meet deadlines. We’ve kind of gone around in circles a couple of times trying to figure out different systems, different ways to organize the workflow and we’ve been unsuccessful.”

In their struggle to find a balanced workflow and structure, NML experimented with editor positions. The four returning students from last year — Noah Tesfaye, Aditi Madhok, Kiora Engelmann and Emilio Sanchez-Harris — are editors in name; their position was intended to essential serve as mentors while also pursuing individual projects so they wouldn’t have to repeat the curriculum. However, this isolated the editors from what the 21 new students were doing. A recent change in structure — removing the editor positions — allowed the editors to take a step back as to become more integrated with the class.

“We weren’t working that well as a team together and that’s the main essence of NML,” Kiora said. “You need to work as a team, you need to work with other people. It was just four of us so we weren’t really communicating with each other… and I think that led to our downfall.”

This can also be accredited to the lack of equipment, time and amount of students. The price for what Barker calls “snazzier announcements” is students staying up well after midnight to finish creating and uploading the videos.

“It’s like running a business but you only have four periods a week to kind of figure all this stuff out, sort it out and do it and it’s just not enough time,” Barker said.

Despite the growing pains, NML has, from the ground up, provided students with the essential knowledge of media literacy. In an era of fake news and information only a search away, media literacy is something everybody needs. And the class slowly making its name known across campus.

“We wanted to create a place where students who felt like they had stories to tell had a place to tell those stories especially if they weren’t students who were geared toward telling them in print,” Barker said. “I didn’t want to create some kind of cliché, greenscreen, two kids in suits pretending they were 40-year-olds sitting at a desk telling the students the school news.”

The class’s main goal is transforming students from passive to critical media consumers. The students develop critical media literacy skills through analyzing discussing ostensibly trivial factors like background audio, sound bites and represented perspectives that can be used to bias and manipulate media.

“[New Media Lit] really opened my eyes to what social media does to people,” NML junior Daisy Herrera said. “Every day we have in our hands access to so many things, and we’re able to see so many things that sometimes, we don’t even know that there’s another person on the other side of the screen wanting us to… change our perspective.”

Make or be made — it’s the NML motto. It’s the motto of a class that is determined to break away from Brave New World-esque mindless media consumption and create important, relevant broadcast journalism. Daisy gives a big smile when talking about her favorite part of NML.

“Interacting with other students and seeing how much they develop — I mean we’re all pretty much quiet,” Daisy said. “We didn’t really know anyone in the classroom but now we’ve grown so much together and now we’re on the announcements which we never thought we were going to do.”