Coming to school every day can be challenging for anyone. Packed schedules, staying on top of homework, and high expectations often overwhelm us. But for 141 of our fellow students, a roadblock many can’t imagine adds to the pressure: not knowing the language of their peers and teachers.

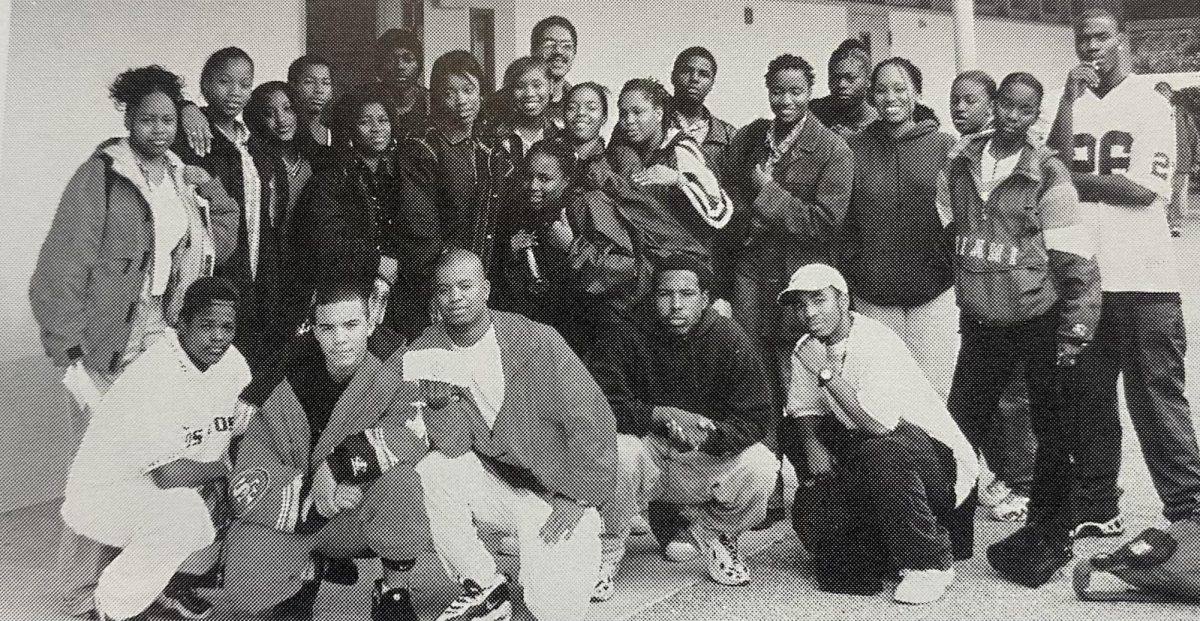

The English Language Development (ELD) programs at the Mountain View-Los Altos School District began in the 1990s as a response to an increasing number of students who did not speak English coming to the school district.

In 2009, the ELD department at Los Altos High School was controversially consolidated into one program at Mountain View High School. The program returned to LAHS in 2022, but the transition has not been as smooth as many hoped. As LAHS attempts to create a supportive program, students in ELD still face serious challenges — many of which are outside of school.

This Talon investigation looks into the experiences of students in ELD, and the controversies of consolidation and mainstreaming. Students quoted in the article have chosen to remain anonymous, so pseudonyms are used throughout to respect their privacy, and some personal details have been changed as well.

Breaking the “ELD kid” mold

For many students in ELD, transcending the label of “ELD kid” at school is a challenge. Surrounded by American culture and English, their departure from the norm can feel alienating.

“In my science class, I’m just the ELD kid,” ELD student Valeria said.

When The Talon asked students how they would characterize students in the ELD program, some responded with words like “less smart,” “stupid,” “unsuccessful,” and “those kids you see in the hallways skipping.” While these perceptions were far from a majority, there clearly is social baggage that comes with being a student in ELD.

“I think some of them put a lot of effort into school but I see most of them not trying at all,” an LAHS student said. “They don’t show up to class. I had one friend who was in my engineering class, and he would just never show up to class. He didn’t really care.”

Comparing ELD students’ academic success to that of their native English-speaking peers fails to consider the vast challenge of a language barrier.

“There’s this misunderstanding that if somebody doesn’t speak the language most people speak, they are unintelligent,” Spanish teacher Dayana Swank said. “That is not true. When students in ELD are in my Spanish classroom, they feel understood. People don’t look at them like they are dumb.”

“I wish people knew how hard I try,” Valeria said. “When people in my classes see I have Bs and Cs, they judge me because they have As, but they don’t know how hard I worked to get to those Bs and Cs in the first place. I’d like to say I’m working even harder than some A students.”

The immense effort many students in ELD have to apply to their academics to succeed can go unnoticed by the school community. For Valeria, simply motivating herself to try in class is difficult due to the language barrier.

“I love school, I really do, and I am glad to see Los Altos is actively doing stuff to make me feel included, but sometimes it’s really hard,” Valeria said. “I feel like I have no choice but to give up. It’s really scary to be in class sometimes because even talking in English is a lot of effort. But I hope it pays off. I want to be something.”

Equally impactful are the social effects of a language barrier. Often only thought of as an “ELD kid”, Valeria finds it challenging to participate and connect with peers.

“I wish everyone knew I was actually just a normal kid,” Valeria said. “It’s much harder to interact with other people. The other day I saw a girl wearing clothes from one of my favorite artists, and I wanted to talk to her. I just didn’t know how.”

Financial Struggles and Moral Compromise

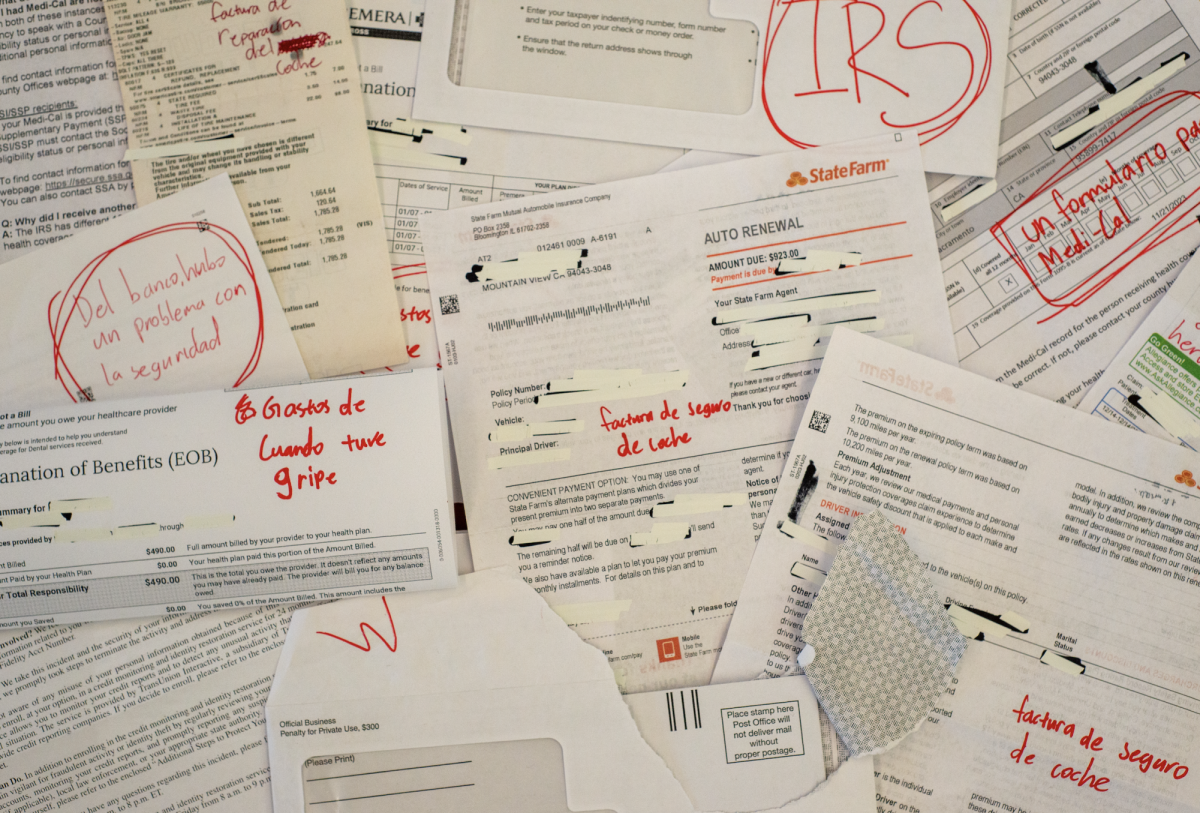

There is a significant overlap between the population of socioeconomically disadvantaged students at LAHS and students in ELD. Based on informal polling conducted by The Talon, a majority of students in ELD identified as needing a job to support their families financially.

As such, many students in ELD end up working to support their families. For some, that comes at the expense of their education.

Jose came to the United States in his freshman year, balancing schoolwork with a part-time job. His parents, who both work over 16 hours a day, also left Jose with the responsibility of caring for his younger siblings.

At first he tried to juggle everything — school, work, and family obligations — but eventually the exhaustion and stress became too much.

“I wanted to do my own work,” Jose said. “But it was all too much at the time. I was already running on empty.”

The cheating started small. A bag of Flamin Hot Cheetos for math answers once a week, a couple dollars for a science lab report when needed. However, as time passed, the transactions became more routine. Homework, quiz answers, and even whole projects were outsourced.

“I used ChatGPT first,” Jose said. “But sometimes it just wasn’t right, or it was too obvious, or it wouldn’t know the answers.

Jose is more than just a student. He’s a caretaker for his siblings, a provider for his family, and a translator for his parents. All of these additional responsibilities are more common for students in the ELD program.

“How many times have you used ChatGPT in the last week?” ELD student Daniela said. “I bet other kids use it just as much as us, if not more. But at least we have a reason.”

“It’s not that I don’t care about my education,” Jose said. “It’s just that family comes first.”

Attendance

For many students, attending school regularly is a given. But financial and family responsibilities can make attendance a challenge.

Lucía, another student in ELD, misses up to six class periods a week in order to work at a local restaurant to support her family financially.

“It’s really hard for me to come to school regularly because I have to help my parents with money,” Lucía said.

Lucía’s story reflects a larger issue: chronic absenteeism — a term referring to a student missing at least 10 percent of school days in a year. This issue goes beyond the ELD program: Throughout California, 18.6 percent of students are chronically absent. Though LAHS has a significantly lower rate of 12.7 percent, teachers still notice the effects.

“Attendance becomes an issue when students are chronically absent,” Spanish teacher Antonio Murillo said. “Each class builds on the next, and students start falling behind. Students can make up assignments and get a grade for them, but you miss something along the way from not being present and practicing.”

“It’s become normalized for students to miss class or leave during lessons,” English teacher Michael Kanda said. “If students are less prepared, they participate less. That has a ripple effect on the whole class. We need to make attendance a greater priority.”

Attendance is an issue for students of all demographics at LAHS. But when it’s combined with the extenuating circumstances many students in ELD face, it can be especially detrimental.

Consolidation and controversy:

According to MVLA Board reports from when the program was consolidated in 2009, the decision was made to provide a more well-rounded education for students in the ELD program by combining shared resources.

However, the decision was contentious. According to data from MVLA Associate Superintendent of Education Teri Faught, the ELD program at LAHS had 50% more students compared to its sister program at MVHS. The consolidation forced students to pick between commute times of up to an hour to remain in ELD, or to continue at LAHS in mainstream courses.

“I remember my brother was very frustrated when this first happened because he was set on going to LAHS for his first year and then his plans changed,” Daniela said. “We just lived much closer to Los Altos than Mountain View.”

Some, however, believe the decision to consolidate the program was made with more than just the reasons given by the MVLA Board of Trustees.

“We were asking our most vulnerable students to now all of a sudden have this extra commute to get to school every day,” former LAHS ELD teacher Arantxa Arriada said. “In my opinion, the consolidation occurred because we had more ELD students, and our academic performance index and test scores were lower than Mountain View’s. By moving the students over, the scores would be more balanced. I will say that as an ELD teacher at the time, I was not consulted at all.”

Return of the ELD program and mainstreaming:

Throughout the process of writing this article, 34 teachers and administrators declined to comment. The ELD department as a whole commented, but the three ELD teachers declined to comment individually.

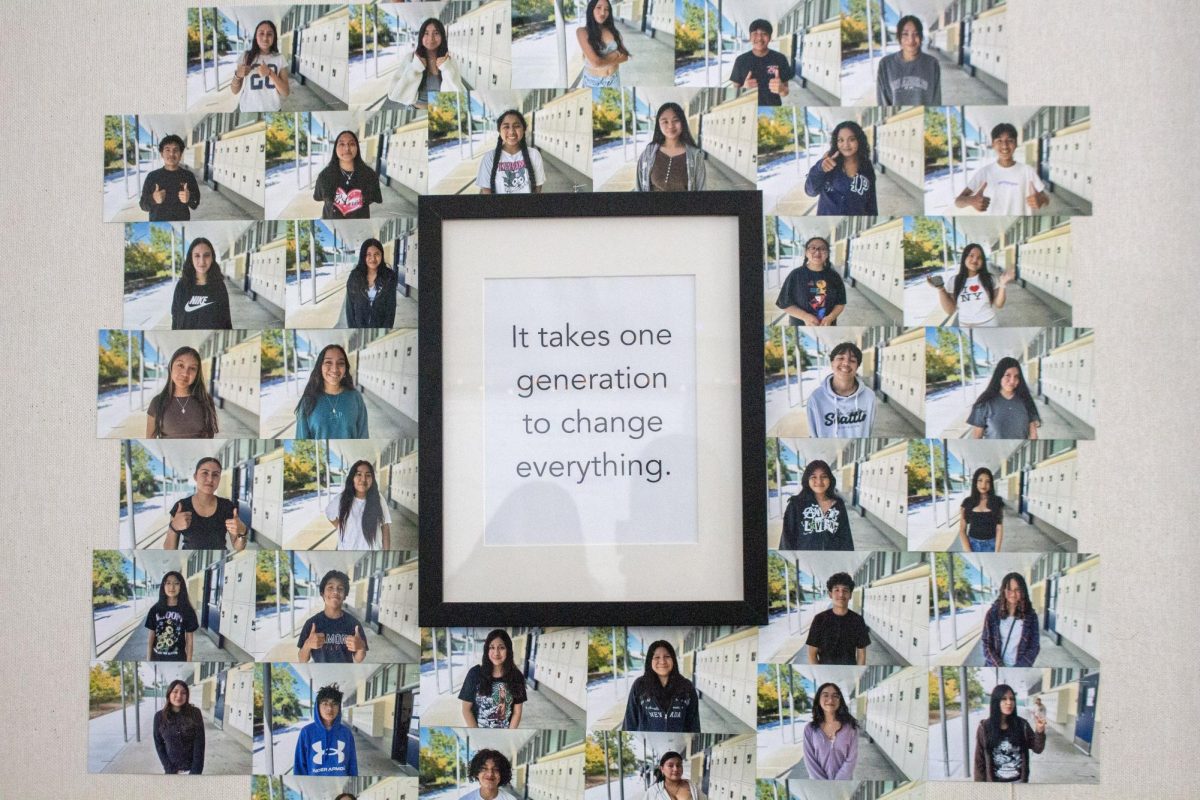

Following years of complaints from parents and students, the ELD program was reintroduced to LAHS in 2022. This meant students learning English spent at least one period a day in an ELD class, which both taught English and supported their school experience.

The ELD program currently offers four levels, ELD 1 through ELD 4. Students are placed in a class based on their results on the English Language Proficiency Assessments for California.

Additionally, students had the option of spending the rest of their periods in Specially Designed Academic Instruction in English (SDAIE) classes, helping ensure students in ELD could engage meaningfully with core content subjects. SDAIE classes are designed for students to be able to simultaneously learn English as well as the core subject.

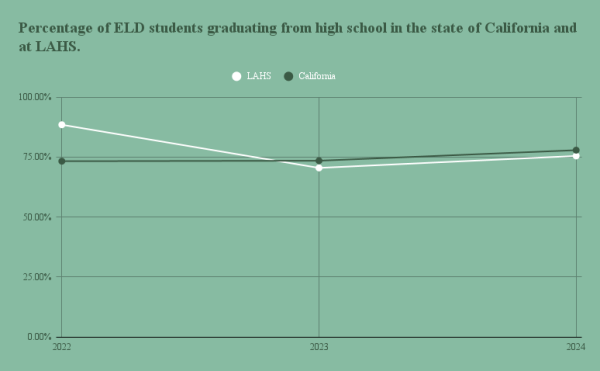

There have been struggles since the program’s return. The California School Dashboard has consistently found LAHS’ English Learner Progress — the percentage of students that increase their ELD level — at least 10 percent below California’s average. However, by graduation rate, the LAHS ELD program has been above or within 2 percent of the state as a whole.

This year, there has been a change. ELD 3 and 4 students were placed into some regular college preparatory classes this school year. This replaced their usual SDAIE classes in a process called “mainstreaming” — though students in ELD still have a dedicated ELD class period. Mainstreaming puts students in ELD in classes with native English speakers. Few SDAIE options remain this year after ELD levels 3 and 4 were mainstreamed.

Students who were mainstreamed might not have many classes where a majority of students are in their grade. For example, a junior in the ELD program may be taking a math class with primarily freshman or sophomore students. Students in ELD levels 1 and 2 still have more support classes than students in ELD levels 3 and 4 — and options to take remaining SDAIE classes.

“ Inclusive classrooms provide our multilingual learners with greater access to a rich and equitable curriculum while fostering community and meaningful engagement with all peers,” Faught said.

Administration, teachers, and students express mixed feelings regarding this new development.

“I understand the theory behind having these kids be in grade-level classes with their peers, but it just feels too soon,” Arriada said.

Mainstream courses can be overwhelming for students in ELD. In English Literature, for example, which is a senior college preparatory English class, students read Invisible Man.

“That book is hard for a kid who was born here, nevermind a kid who is trying to navigate this new language,” Arriada said.

Being overwhelmed by English content can be demoralizing to the point that some students disassociate at school. But being in a classroom with younger classmates could have similar effects.

“Students deserve to be in classes with their grade level peers,” Principal Tracey Runeare said. “We are supporting students in the content classes with aids for now, but it is hard — we don’t deny that.”

However, Runeare believes with the right instructional strategies, students in ELD can succeed in mainstream classes.

“You can teach content and language at the same time,” Runeare said. “It might look different for different students, and it might look different in different classes. There are a lot of strategies that can be used beyond using a student’s primary language to support learning.”

In visual-heavy classes such as dance and physical education, mainstreaming has been very positive for some students in ELD.

In visual-heavy classes such as dance and physical education, mainstreaming has been very positive for some students in ELD.

“I don’t really mind having classes with the other kids because it allows me to meet new people,” Jose said. “It’s not just me and other ELD kids. I like meeting new people. I’m in PE this year, and I can talk to tons of people and exercise with them, because it’s just PE. You don’t have to be smart to participate in PE.”

“They do really well mainly because we get to lead by example and visually demonstrate things,” physical education teacher Kiernan Raffo said.

Kanda believes mainstreaming students in ELD is necessary at some point, but that the school is rushing and inadequately prepared for the shift.

“Some people are resistant to change, and I do think including as many students as possible is a worthy goal,” Kanda said. “But that leads you to think about what the true definition of inclusion is. I heard at a Constructing Meaning meeting to ‘expect more Ds and Fs in your classes’ because of this inclusion.”

In order to make sure students in the ELD program are adequately supported on campus, the district has given teachers access to multiple professional development courses to help support students at MVLA.

One of these professional development courses is called Constructing Meaning. According to Constructing Meaning’s website, its goal is to train teachers to create tangible expectations in the classroom for struggling students, though it is not a program created to directly address the needs of the ELD program.

“I spent around 100 hours attending Constructing Meaning and for related curriculum changes,” Kanda said. “I think it’s pretty good overall. But, it doesn’t matter how much training or support I have. It’s still going to be a struggle.”

Conclusion

Though the ELD program has struggled since its return, it has seen improvement in recent years, such as a five percent increase in ELD student graduation rates from 70.5 to 75.5 percent. However, challenges persist, both academically and socially.

The hardships ELD students face — language barriers, social alienation, and financial difficulties — can be an invisible but suffocating burden.

“My classmates don’t know that I am actually really smart,” ELD student Sofia said. “They don’t know how hard I try, or how much I like to learn.”

But despite the fact that many struggles faced by students in ELD exist beyond high school, the ELD program has been and will always be there to help students.

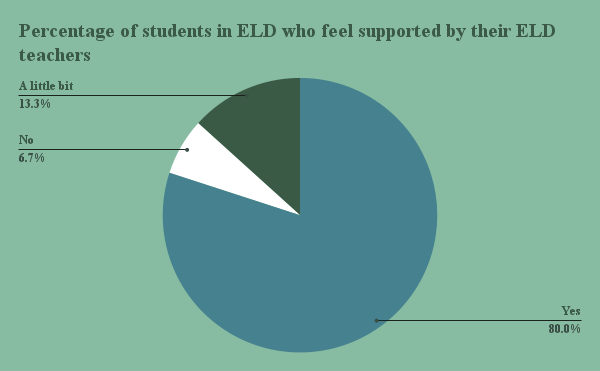

“I actually feel very supported by my teachers here,” Sofia said. “My ELD teacher is really nice to me. She takes the time to talk with me and get to know me, which is more than a lot of people here. I like this program a lot.”

La versión en español de este artículo se puede encontrar en: https://lahstalon.org/perdido-en-la-traduccion-la-experiencia-eld/