Kulture à la Kaavya: Pronounce my name right, please

Copy Editor Kaavya Butaney writes about how her name has been mispronounced her whole life and how that reflects broader trends in America.

My parents spelled my name incorrectly on my birth certificate. Well, sort of.

See, my name is spelled K-a-a-v-y-a. Most people spell it K-a-v-y-a. I asked my parents about it when I was 12, and they told me that they decided on the double a to make it easier to pronounce (spoiler alert, people still mispronounce my name). And the exact same thing happened with my last name, Butaney. It’s usually B-u-t-a-n-i or B-h-u-t-a-n-i, but some ancestor of mine decided to roll with the punches and change the spelling of his name.

It’s confusing why people mispronounce my name because it’s not that hard. How is Kaavya harder than Michael or Yvonne or god forbid, Timothee Chalamet? But I’m not going to scream at someone who asks me how to pronounce my name because that’s both rude and pointless.

The issue doesn’t lie with the typically European-derived names of America. It doesn’t lie with my middle school classmates. It lies with something much larger.

People refuse to learn to pronounce names, and just keep going, even if they know it’s wrong. Twenty or so years ago, my dad’s coworkers couldn’t seem to learn to pronounce his name, so he went by “Vik” instead of “Vikas.” Both of my brothers have gone by Americanized versions of their names for most of their lives and just shrug off the mispronunciation.

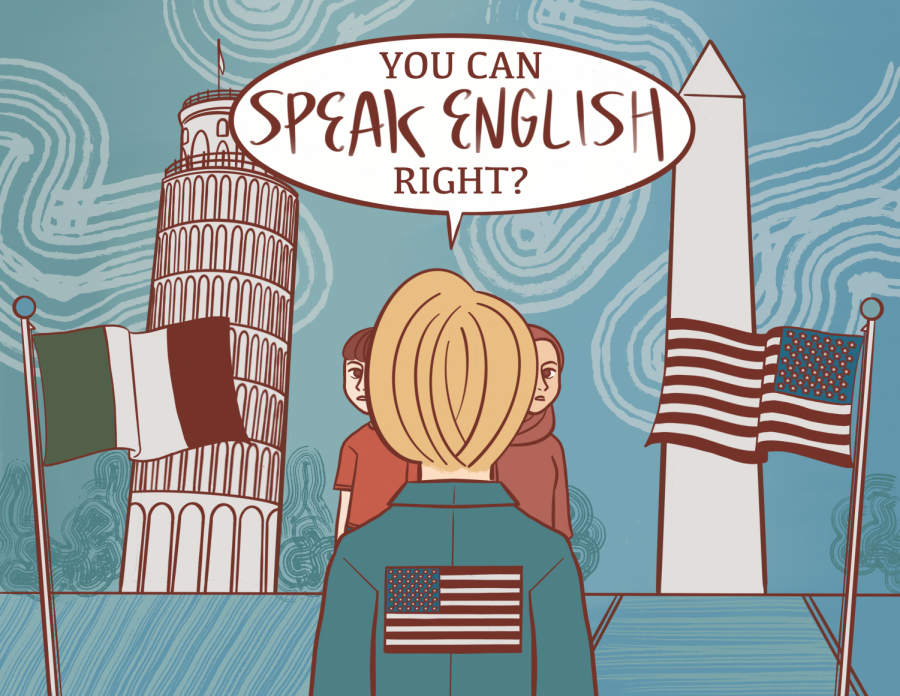

This is all because of something I call the nationalist mindset. Most Americans don’t like to learn about other cultures. We don’t like to know about other things. Everything is centered on America, from pop culture to technology, and because of that, many are under the impression that we live in an America-centric world, and nothing happens anywhere else.

But no. Things happen all over the world, and they matter. They deserve respect as much as any American.

So many Americans assume that people can locate Nebraska but can’t distinguish whether the word Namaste is Japanese or Chinese. There’s this inherent belief that everyone speaks English so when an American goes to Italy and people don’t understand them, they find it irritating. But cue two weeks later, they’re back in America and expect tourists to be fluent in English.

Although English is considered the worldwide lingua franca and America has a massive impact on the world, that is no excuse to believe that we are the center of the universe. While it isn’t too absurd to believe that people speak English across the world, it is incredibly absurd to believe that every person on the streets of Thailand will be fluent.

I can’t tell you how to fix the mindset of an entire nation at once, but it is definitely possible on the individual level. It’s basic empathy. Learn how to pronounce someone’s name properly. Try to accommodate others who don’t speak your language.

I fully admit that I am not perfect at this, often falling into the trap of believing that everyone will understand what I mean by “San Francisco Bay Area,” but I’m doing better. We have to be better people and just try to think of the big picture because when it comes down to it, the US is just one country among 195.