← Back to “What Does it Mean to Be American?”

Life for first-generation Americans like sophomore Sarah Yam is a mix of cultures and patriotism. It’s a constant clashing of the “Pledge of Allegiance” and the “Hora”; it’s a fierce battle between hot dogs and spicy curries. Even though as elementary kids, we sang “It’s a Small World After All,” it really isn’t—and definitely not for first-generation Americans. Because sometimes, their world is too big with both hot dogs and spicy curry, and life for the first-generation is a story of juggling all their inheritances.

Sarah’s mom was born and raised in Hong Kong, while her dad born in Japan but brought up in America. As a child of two immigrant parents, each with their own culture, Sarah keeps and practices the traditions of her ancestors. Her family celebrates both Chinese New Year and the Lunar Festival, but nowhere on the scale of a massive celebration. For the Yams, these holidays are more like family gatherings filled with a variety of steamed delicacies instead of a festival full of huge explosions of firecrackers, colorful masks and red lanterns.

Like Sarah, sophomore Sitar Terrass-Shah is a first-generation American. Her mom was born in America, and the maternal side of her family has lived in America since the 1600s; but her dad was born and raised in India. And like Sarah, she maintains a strong sense of culture, but instead of the Lunar Festival she attends Diwali parties.

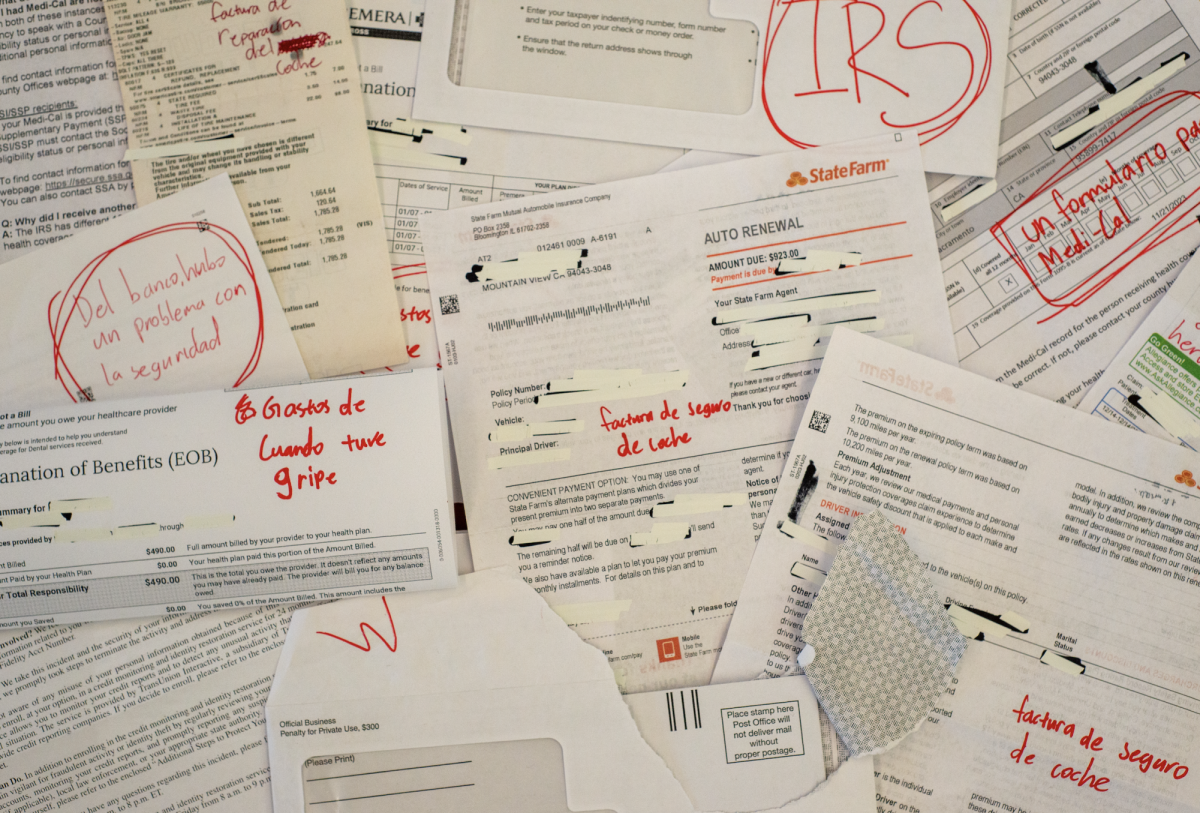

But for Sarah and Sitar, as much as they love their family and cultures, holidays are but a handful of days out of the year. For the other 364 days, life isn’t about firecrackers and samosas, but about school. As such, daily life, even the menial bits like listening to the radio on the way to school, shapes their lives as much—if not more—than their home culture.

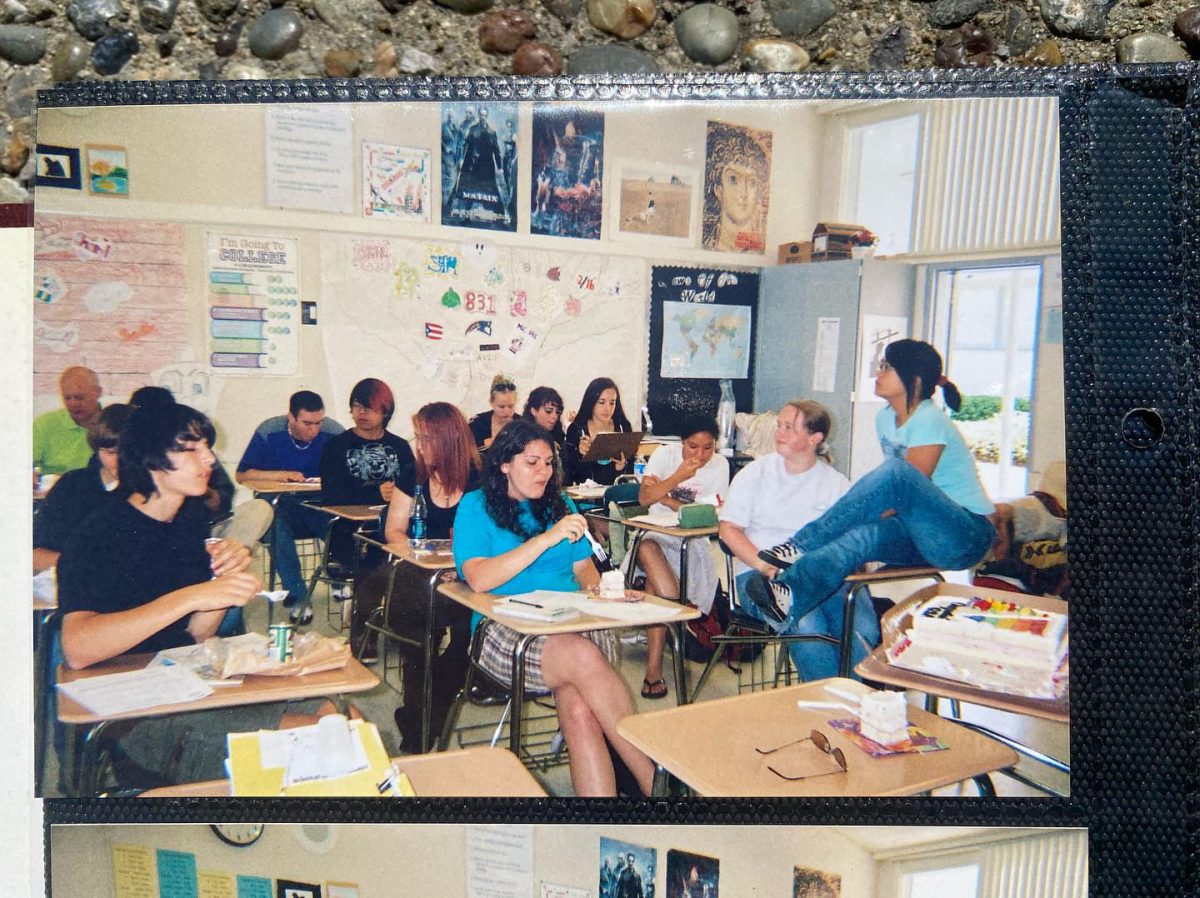

School isn’t just a place where we sit at a desk and count the dots on the ceiling or doodle in a notebook; it’s a place where we are exposed to a variety of different cultures, opinions and perspectives.

“The United States, especially the California Bay Area, is incredibly diverse,” Sitar said. “I grew up knowing a lot more about other cultures, including my own, than I would have in another country or region. I have friends of many backgrounds and am generally more open-minded about people with ideas that differ from my own.”

Both Sitar and Sarah argue that their exposure to different cultures—at school and at home—allows them to form their own morals and standards. The mix is wonderfully new and unique. First-generation Americans, unlike their predecessors, are free to pick and choose the cultural touchstones they want to carry, but at the same time they’re free from the burden of institution and establishment. They have the unique gift to decide who they want to be.

“If children grow up in a diverse environment, they tend to be less judgmental,” Sitar says. “If they have friends from other countries, that country becomes more real to them; rather than being just another place across an ocean, it is the home of people they love.”

America is a place where cultures from other countries collide to make a country of unique perspectives. All citizens are different since they live according to their own standards, and this is why we see so many innovative ideas.

“America is a [place] based on immigrants who originally came from England, so honestly America itself is a mix of cultures,” Sarah said. “Other cultures and ideas add to it.”