A Brief History of Title IX

In a world where women’s volleyball games are selling out football stadiums, it can be jarring to imagine a time when women’s sports were barely recognized. Now, here’s the real kicker: that was just 51 years ago.

Title IX was the game changer. It’s a landmark law passed in 1972 that prohibits sex-based discrimination and harassment in all education programs and activities that receive federal funding. The result was a shift throughout all sectors and industries, from education to healthcare to engineering. The bill was not originally intended to protect women’s sports, but its generalized nature allowed it to address issues in women’s athletics.

To say Title IX revolutionized gender equality would be an understatement. Before its establishment, only 12 percent of females held college degrees, and the few women accepted into colleges often faced prejudice and harassment. Most colleges had separate entrances for male and female students. Both men and women were prohibited from taking certain classes; female students were not allowed to take auto mechanics or criminal justice, while male students couldn’t take home economics. The cultural consensus was that women seeking higher education were selfish, and should instead settle down to start a family. Elite female athletes at the time, such as Donna de Varona, a gold medalist Olympic swimmer, could not find scholarships to play their sport in college. They simply did not exist.

Activist Bernice Sandler, known as the “Godmother of Title IX,” sparked a series of important court cases that led to the creation of the famous bill. In 1970, Sandler was denied a teaching position at the University of Maryland because her behavior was “too strong for a woman,” according to the National Women’s History Museum. Furious, Sandler worked with Representative Edith Green to compile evidence on sex-based discrimination in education, including testimonies from other women harassed into leaving math and engineering classes.

In the past 51 years, the law has helped women gain equal access to higher education and academia, challenge gender stereotypes and obtain protection for those pregnant or parenting. Even outside of the classroom, Title IX applies to sports of all levels, from elementary schools to National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) programs. In a study from the National Federation of State High School Associations (NFHS), directly after Title IX’s establishment, girls’ participation in high school sports rose by over 175 percent from 1972 to 2008.

However, Title IX is not without its opponents; it’s often mistakenly blamed for forcing schools to cut funding for men’s athletics to balance out extra funding for women’s programs. In fact, since its creation, Title IX has received 20 court challenges, many arguing that revenue-producing collegiate sports, such as football, should be exempted from Title IX rules. Yet, funding for men’s sports programs and the number of male student-athletes have also increased since Title IX’s establishment; the same study from the NFHS states that all high school athletes have increased by 98 percent and in college, 160 percent.

This continued attack on Title IX shows that despite the law’s benefits, gender equality in education still has a long way to go. On average, female NCAA Division I national championship participants receive $1,700 less, per person, than their male counterparts, despite making up almost half of all Division I athletes. Although overall sports participation rates have grown across the board, females’ athletic support and recognition still lag behind that of their male counterparts.

Despite the work that remains for gender equality, the successes of female athletes this year — from international competitions to LAHS’s own student-athletes — are proof that efforts, however big or small, have paid off. As we look out to the changes that can still be made, we can also reminisce on the great advancements and successes achieved by female athletes, thanks to Title IX.

Student Opinions

Title IX continues to shape high school athletics nationwide, including at LAHS, shaping how athletes participate in school sports and plan their future in athletics. On this topic, The Talon interviewed four LAHS female athletes: varsity track sprinter sophomore Daniela Hughes, varsity tennis player junior Tyra Bogan, varsity golfer senior Chihiro Niki and varsity distance runner senior Maddy Randall. Here’s what they have to say.

Do you feel like you have the opportunity to pursue a career in your sport?

Tyra: I don’t think so. It’s my goal to play in college and maybe go professional for a little while, but honestly, it just does not pay well enough on the women’s side.

Maddy: Certainly, especially at our high school, we have so many opportunities; we were able to run at nationals, and our team certainly gets recognized for our achievements. I’ve never felt like I don’t have the opportunity to go far enough.

Dani: I definitely do, especially because Los Altos has a really strong track program. Last year the girls team won CCS for the first time and we were able to go to states, which was a huge accomplishment. I think another thing that’s great is how my coaches and teammates really support my ambitions and do their best to help me.

How do you feel about stereotypes around women’s sports being less interesting or entertaining than men’s sports?

Tyra: Females may not be as physically strong or as fast as male athletes, but that doesn’t make the game less entertaining. Rather, it changes the game. There’s more technique involved rather than just sheer power and will.

Maddy: Men’s sports are glamorized far more than women’s sports, and there’s just an endless loop of people watching men’s sports because they’re already more popular, and people think women’s sports are boring just because it’s already less popular.

What’s your hope for the future of female athletes?

Maddy: It would be great to increase access to watching women’s sports; the majority of games on TV are men’s sports, and there’s basically no advertisement about women’s sports or women’s leagues. If more people knew about it in the first place, women’s sports would have much more ability to grow.

Dani: I hope women’s sports will get the same airtime as men’s. So many women’s talents go unrecognized because they just aren’t getting the same screen time and coverage as men. I also want to see women get more opportunities in brand deals and sponsorships.

Where’s the Money at?

It’s no secret that women’s sports generally receive much less hype, funding and viewership than men’s sports, but why? Is a smaller audience causing the lack of enthusiasm, or does the lack of enthusiasm discourage spectators?

This vicious circle continues to persist today, where men’s sports are given more media attention than female sports, so their players gain more interest and generate more money, fueling the pay gap.

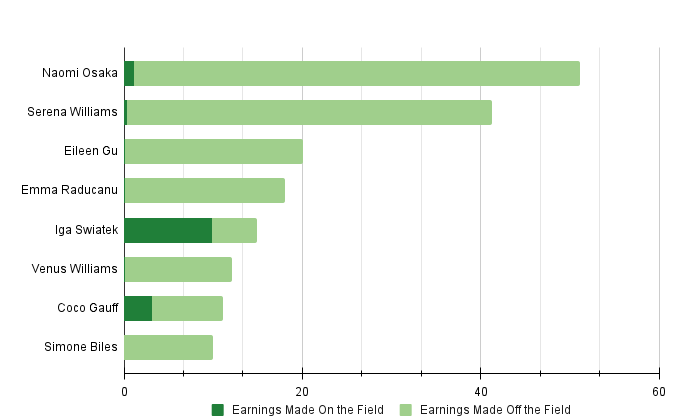

So, in reality, it’s not that female sports are less interesting or important, but lack of media attention for those sports leads to fewer views and ticket sales. Below is a comparison from Forbes of the world’s highest-paid female athletes and the world’s highest-paid athletes between May 1, 2022, and May 1, 2023, along with their combined earnings made on and off the field.

A Battle for Title IX

Anne Battle, ‘71, is a true jack-of-all-trades athlete. She was recruited to Stanford for tennis during a time where women weren’t given as many opportunities or rewards as men in sports, and her LAHS legacy continues through her daughter Lisa Battle, an English and Drama teacher. 51 years after the passing of Title IX, Battle now reflects on her experiences as a female athlete in an era pre-dating the monumental bill.

Battle was born and raised in the Bay Area and has lived in Los Altos for most of her life. Her love for sports was fostered by her two older brothers and family of tennis players.

Battle particularly remembers her own experience of playing basketball for a girl’s team in elementary school and the restrictions they were forced to follow. When Battle was in high school, Title IX was still several years from being introduced: there were few opportunities dedicated to female athletes and most womens sports weren’t taken as seriously as male sports were. Because of this, Battle was often left on the sidelines.

She attributes the difficulty of joining pick-up games — unofficial games created spontaneously — to the fact that she was a girl.

“I loved the stuff my brothers were doing. I was always a tagalong,” Battle said. “I spent my whole childhood excited to participate in any way and trying to be allowed to play something.”

The struggle did not end there. During her time at LAHS, Battle played for any team that would let her. One of the few legitimate girls’ teams they had was tennis, which she took up quickly. But Battle’s true passion lay in team sports. Some nights she would play for the soccer, basketball or football teams — which almost always consisted of boys — but she was never officially on the roster.

“I had fun in high school because I could literally play on any team,” Battle said.

Battle felt this was where she belonged. She was welcomed, but there seemed to be a general lack of support for female athletes. On television, Battle rarely saw her interest in women’s sports reflected; the most major publicized event featuring women was the Olympic Games, and even then that was only once every four years. At school, most of the male games were well attended and publicized while the womens’ games were not. Battle recalls that the difference in coverage was apparent even in the LA Times — the student newspaper at the time — where entire pages would be solely dedicated to male sports.

“The way they taught girls basketball was that they didn’t think girls should run very much,” Battle explained.

When she played on a women’s team, they had designated runners to cross half-court and, at some points, they could only move within a certain area while playing. The intention was to prevent them from running, as it was believed at the time that women could only handle so much physical activity.

Battle was repeatedly told not to be too competitive, run too fast and hit too hard. But she didn’t let that stop her. Battle was recruited out of high school and went on to play tennis in college for Stanford.

Battle longed to be more involved in the sports she saw men playing, so she began pushing for more spaces for women’s sports on campus. She helped create a women’s basketball team at Stanford and attempted to create a women’s soccer team. Soon, Battle realized that one of the main issues was that women simply weren’t taught how to play.

“Usually I was the only one who had ever played basketball, real basketball,” Battle said.

With every obstacle she faced, Battle remained composed. She continued to do what she loved by playing intramural sports on co-ed teams like flag football, cornhole and ultimate frisbee.

Although Title IX came into law Battle’s freshman year of college, it was years later that it really came into effect. While Battle herself couldn’t experience its full effect during the prime of her career, she watched as it changed the world in which her daughter would grow up to play.

“I wasn’t angry,” Battle said. “I was just wishful.”

Battle broke barriers before they were widely acknowledged or dealt with at all. Her tenacity, drive and love for competition represent the true heart of an athlete, speaking for impassioned female athletes who struggled with gender inequality just as much.

“They’re just doing what they love,” Battle said.