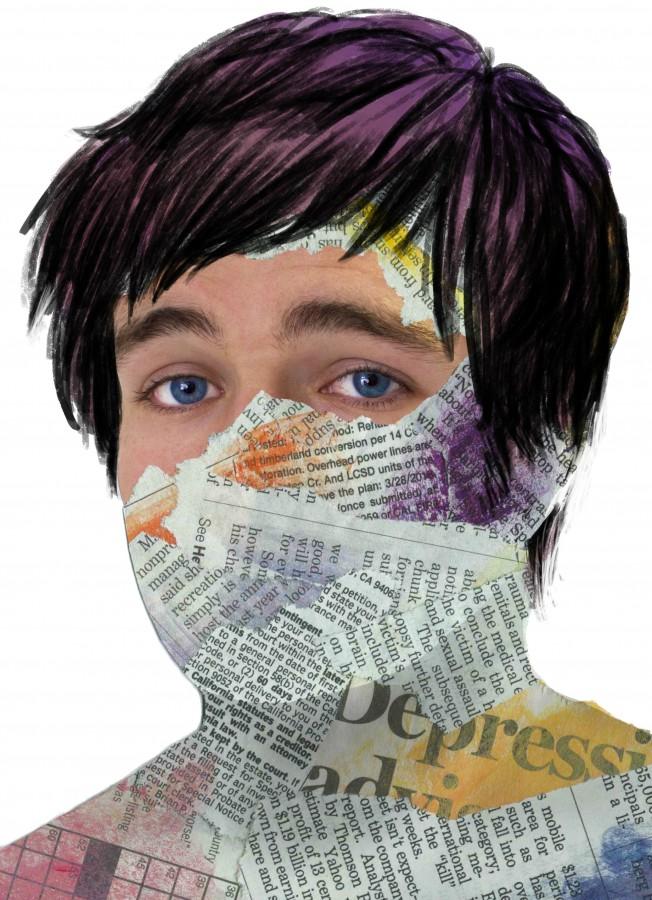

“I’m So Depressed.”

Take a second and look up from wherever you’re reading this. Picture yourself in your first class of the day. Look around and take note of the faces you see every day. In the average class of thirty students, six suffer from a mental illness. It might be the kid who sits right in front of you, or the kid who sits a few rows toward the back, and it might even be the kid who sits right next to you and greets you every single day.

Teenage emotions are blurry. They flip and flop, they don’t fit snugly under generalizations; they’re not just winding roads, they’re mazes. In contrast with the relatively straightforward, quantifiable feelings of adults, it’s difficult to categorize the hormone-fuzzy emotions of the high school demographic. Most of the time, this is okay — we weave through our mental mazes, finding our way despite our wrong turns and occasional dead ends, retracing our steps and learning from mistakes. But sometimes, through a combination of chemistry and environment, these adventures take a darker turn. The line between emotion and mental illness is blurred, and even crossed, and identifying the border between these two closely related terms is one of the first steps toward treatment.

First, some biology: As we begin to experience more and more complex emotions, neuronic activity in the brain forms certain patterns that are then associated with specific emotions. Scientists have concluded that these feelings are linked to biochemical reactions through our entire body, caused by external factors. So, for example, when we first hear a friend talking about us behind our back, a slew of difficult emotions is produced: anger, jealousy, embarrassment, disappointment.

But this developmental process isn’t the same for everyone. While it may seem that identifying these emotions is pretty straightforward, the truth is that teenagers often don’t have enough experience with their own emotions to sort out their feelings. The time from teenage to adult emotional maturity involves changing the way we think, and that can take a different amount of time for each person. The chemical wiring of our brains just doesn’t allow us to think in the same way adults do — which could explain why we never seem to get along with our parents. When we interpret the emotions of those around us, we’re using the same part of our brain that controls our own emotions. Adults, on the other hand, use the parts of their brains that control logic and reason, which is why we’re sometimes perceived as selfish or unempathetic.

However, there’s another, more significant explanation for our behavior. Because we often don’t even know what combination of emotions we’re feeling, we can’t always predict or control our reactions. For example, when our homework loads begin increasing as we progress through each grade, we will often behave more sensitively without knowing exactly what’s bothering us.

In a similar out-of-our-control way, mental illnesses are never acquired by choice, and aren’t as easy to “fix” or get rid of as our natural emotions. Though the exact causes of most mental illnesses are unknown, science has linked them to three different factors.

Environmental factors, such as the death of a loved one, a dramatic shift in one’s life or a form of substance abuse can induce mental illness. Mental disorders can also be traced through families, indicating that one or multiple gene malformations could play a key role in someone’s diagnosis. Certain problems with an individual’s brain and nervous system are also potential causes for mental illness.

The ability to sort out and explain our own emotions allows us to differentiate between our natural emotions and potential mental illnesses. We begin to understand that what sets mental illness apart from our natural emotions is when one’s ability to overcome negative feelings is impaired.

Signs of mental disorders are often ignored because teenagers are branded as emotionally unstable, with shifts in overpowering emotions written off as the result of hormones and puberty. In other cases, the fault is ours because we aren’t always cautious with our choice of words to describe what we’re feeling. An adult might hear a student say they feel “depressed” after taking a difficult test, and assume they’re exaggerating sadness. Consequently, like the moral of “The Boy Who Cried Wolf,” the adult might stop considering how teens say they feel, and possibly ignore a teen who could be severely affected by depression.

Despite frequent misuse in dialect, mental disorders are actually very common and entirely real; everyone feels emotions, but emotional trends that are long-lasting, extreme or unnatural are signs of mental illness. While many students never encounter mental illnesses in their high school careers, hard-hitting statistics prove the reality: 1 in every 5 teens suffers from a diagnosable mental illness. Half of those diagnosed will eventually drop out of high school. Suicide is the third leading cause of death for youth aged 10 to 24, and 90 percent of these victims had an underlying mental illness. The average time it takes someone to intervene in a situation of mental illness is 8 to 10 years — tragically, that’s often not soon enough. The ability for anyone to distinguish between emotions and mental disorders saves lives.

Depression, for example, is a disorder that can be confusing to properly distinguish from the feeling of sadness. When things in life don’t work out, people naturally feel upset. However, this feeling should match the seriousness of the event and fade away within appropriate time. If an overwhelming feeling of sadness or hopelessness lasts longer than two weeks and starts affecting an individual’s life, such as the quality of their work, there is a possibility that a mental illness might exist.

Emotions are weird and mental illnesses are never our choice. There are scientific causes for mental illnesses that are significantly more difficult to overcome than our natural emotions. What we choose to feel and what we have no control over are two different cases that are easy to write-off. However, when it comes to dealing with these cases and the tolls that they take on our bodies and minds, it can become difficult to distinguish the two and properly diagnose our emotions.