Housing Crisis Hits Close to Home

April 29, 2016

Come August, English teacher Carrie Abel doesn’t know where she’ll live. Her lease on a Mountain View apartment shared with two roommates is up by then, and with the rent rising by $600 the last time that happened, she knows she’ll have to move. Even so, Abel can’t start apartment hunting until August because breaking her lease means thousands of dollars in fines.

“It’s very, very stressful,” Abel said. “I look at Craigslist almost every day, just as a maybe. I don’t know what would happen, because if there’s a great place to live, I can’t move into it anyway. But it’s almost reassuring to know that there is something [there] maybe.”

Among LAHS teachers, Abel isn’t alone in her housing troubles; many echo similar sentiments of stress and frustration at the cost of housing in the Bay Area real estate market.

“Everybody’s feeling the same pinch,” English teacher Robert Barker said. “The success this area has had because of Silicon Valley has driven the [housing] market up to unreasonable levels.”

Many believe that high demand for housing and short supply are to blame for the skyrocketing prices. Slow construction in the area, especially of affordable housing, exacerbates the growing issue. At school, the toll of this housing crisis extends into the personal and professional lives of teachers. Locally, growing frustration among residents has spurred many local cities and even school districts to prioritize the search for solutions to a multidimensional problem.

Teachers’ stresses

The MVLA school district ranks as one of the highest paying school districts in the state, with teachers paid an average of $114,000 in the 2014-2015 school year, according to EdData.org. Yet even with a six-figure salary and a potential second income from a spouse or partner, buying a house in nearby cities such as Mountain View or Palo Alto is nearly impossible without financial help from family members or an inheritance.

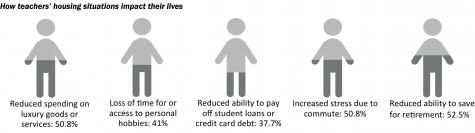

As a result, many teachers move to cities such as Sunnyvale, San Jose, Campbell and Santa Clara, where houses are more affordable, but the commute is longer. In a survey of teachers conducted by The Talon, more than half of respondents cited stress from long commutes as a lifestyle sacrifice they have made due to their housing situations.

“In the afternoon, [I’m] counting minutes,” art teacher Christine An said. “If I get [out] five minutes late, I know that’s going to increase my drive home by 40 minutes. So I get really anxious because I know I have my pets and my family members waiting at home that need my attention, and my work. I’m always anxious about my time.”

The time drain and stress from long commutes also snowball into teachers’ involvement in the school community and ability to interact with students after school. For An, living in San Jose means missing out on the Art Club’s volunteer work and activities.

“I can’t get involved because I live so far away and it takes me so long to go home,” An said. “If I stay here for an afterschool activity or if there’s some event, that means I have to stay here for the rest of the evening until the traffic is lighter, which is at like eight o’clock at night, which extends my work day way too long.”

Many teachers who rent have a longer-term issue, because they struggle to save enough to buy a house while facing increasing rent hikes. Like others, they are forced to choose between closer housing that may be too expensive and less expensive options which mean longer commutes.

English teacher Elizabeth Tompkins lives in a granny unit, a structure located behind a larger housing unit, shared with a roommate in Palo Alto. Tompkins recognizes the situation as unsustainable due to the costs of living in the area, yet finds it difficult to weigh the high cost of closer housing with the lifestyle sacrifices of cheaper housing farther away. When her lease expires in the summer, she does not know what she will do.

“What am I thinking for the future? I don’t know,” Tompkins said. “Palo Alto is crazy expensive. [I’d like] to move to more affordable areas, but there is something really nice [about] only having to commute 20 minutes in the morning versus, [commuting] over an hour to get here.”

Commute aside, teachers stated that the personal financial strain of housing is significant as well. More than half of teachers said they have reduced spending on luxury services and cannot save as much for retirement.

“[My wife and I] have made [sacrifices] really on all levels,” Barker said. “Any kind of discretionary spending has almost stopped. Buying new clothes, going out to eat, ordering in, entertainment, going to movies, traveling.”

The district is beginning to feel pressure to act on the issue. While the district has yet to see a decrease in the quality of teachers it hires, Associate Superintendent of Human Resources Eric Goddard notes that the district has noticed a small trend of prospective teachers turning down job offers to work in MVLA, once they realize the cost of living, something unheard of five years ago.

“[It’s] something that we continue to keep a close eye on,” Goddard said. “If the housing prices continue to increase, I think it’s going to be challenging to attract a wide range or pool of employees to work with our students. We’re going to have to get more creative.”

Is teacher housing a solution?

Some school districts have taken their own initiative by building subsidized teacher housing, where housing units are rented out to teachers at below market rates.

Santa Clara Unified School District was the first school district to pioneer the idea, building a total of 90 units over seven years. The initiative proved effective; the attrition rate for new teachers who took advantage of subsidized housing was 8 percent, compared to 24 percent for all new teachers.

More recently, the issue has garnered action from local district officials. San Francisco Unified School District and Cupertino Union School District both announced plans late last year to build affordable housing units for their teachers. And during a board meeting last month, Mountain View-Whisman School District board members agreed to consider the idea of undertaking their own development project.

However, skepticism remains about the viability of teacher housing as a catch-all solution. Many districts would have trouble finding the land for new construction, and buying land in Silicon Valley is not an affordable alternative.

“All the land we own is already fully spoken for,” MVLA school district board member Phil Faillace said. “I don’t know where we would find the land, and even if we did [find a piece of land], I don’t know how we would buy it. There are all sorts of problems.”

Others believe that subsidized teacher housing doesn’t address the root of the problem: The average teacher salary precludes teachers from living where they teach.

“It’s a nationwide issue, like why are teachers in general not paid enough to live in the communities in which they work?” history teacher Margaret Blach said. “It’s the larger picture that teachers should be paid more to lessen that burden of housing.”

Meeting demand with supply

For Mountain View Vice Mayor Ken Rosenberg, the issue of housing boils down to supply and demand. If the housing supply stagnates while corporations continue to build more office space, the crisis only intensifies as developers increase prices for profit, and lower-income workers are pushed out of the area.

“In a word, gentrification,” Rosenberg said. “If you really want anecdotal evidence to what’s happening, walk up Castro and count how many help wanted ads you see in the windows. [It’s] a lot. Those restaurants are finding it harder and harder to find people willing to work for those wages.”

Los Altos faces fewer options than its sister cities of Mountain View and Palo Alto do to increase its housing stock, primarily because it is a residential community with few areas for high-density development. However, the city takes steps to contribute what it can to the housing situation by requiring developers to build below market-rate units and mandating maximum land and density usage in development projects.

“How much impact [the city of Los Altos] can have is really kind of minimal… because we’re a totally built out community,” Los Altos Mayor Jeannie Bruins said. “If you look at somewhere like Mountain View, they’ve got a lot of land…[and] opportunity. We don’t have open land.”

Mountain View has begun exploring its opportunities, recently laying out an outline for as many as 10,250 new homes in the North Bayshore area. According to the Mountain View Voice, the city also looks to increase the amount of affordable housing units to 20 percent in the area, a step up from the usual 8 percent for most projects. The result could be over 2,000 new affordable housing units. Yet according to Rosenberg, Mountain View cannot solve the housing crisis by itself.

“We need Sunnyvale, Santa Clara, San Jose, Los Altos, Cupertino, Palo Alto, Menlo Park… we need everybody to do this,” Rosenberg said. “This is all hands on deck.”

For teachers, however, the North Bayshore projects are unlikely to alter their housing options. Homes made available by the land-use plan will likely be doled out to engineers and tech workers, as much of the land available is still owned by Google and other corporations.

“In Mountain View, there are more developments, but they have to be shared with everybody,” Faillace said. “It’s always a small fraction of the population that gets to take advantage of programs like that, so it’s a solution for those people that are lucky enough to get in the door.”

Making it work

As cities like Mountain View seek to tackle the housing issue from a long-term perspective, teachers are left to struggle with their personal housing situations. Abel remains unsure of where she will live from year to year. An will still watch the clock anxiously in the hopes of beating afternoon rush hour traffic, and Barker will continue to sacrifice lifestyle luxuries.

Uncertainty about housing and its accompanying impacts on their lives remains an unfortunate reality for teachers at LAHS. For now, their only option is to just make it work.

“The prospect of never quite knowing where I’m going to live next is very unsettling,” Abel said. “I have no idea what will happen, but I’ll live somewhere. I’ll be fine.”

J. S. | May 30, 2016 at 4:27 pm

Important update: the Cupertino Union School District has stopped the plan to build staff apartments, choosing instead to save the school site that was targeted for future expansion. Totally makes sense given the crazy growth in the Bay Area and overcrowding in schools.

“During the regularly scheduled board meeting on May 24, 2016, the Board of Education approved the staff recommendation to discontinue exploration of employee housing at the Luther Site.” (from the District website)

Time to for the district to work with the community and teachers on alternatives that are long-lasting and equitable, while retaining school sites for future use.