Halloween costumes perpetuate cultural and gender stereotypes

Freshmen Marcos Cardenas-Salazar, Edgar Barajas, Simon Burdick, Nicholas Chippa, and Tenzing Sherpa contributed

to this article.

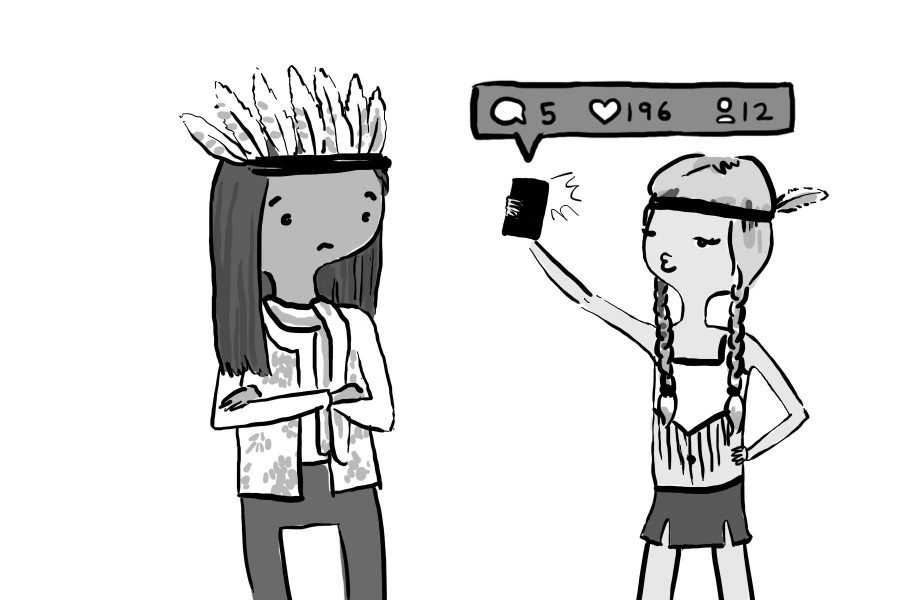

When Halloween falls on a school day, many students dress up in whimsical and comical costumes in playful spirit, participating in school activities and engaging in group costumes with their fellow students. However, students will occasionally and often unintentionally wear costumes that can subtly perpetuate harmful gender and racial stereotypes, typically due to excessive and negative media influence.

While such costumes are sometimes challenging to detect as being outright offensive, all students should begin discussing the damaging gender and cultural stereotypes that certain costumes perpetuate. By increasing student awareness of the media’s influence on costumes, students will have a better understanding of what is appropriate to wear throughout Halloween and other dress-up days.

At our school, adults occasionally spot one or two questionable costumes on Halloween, but most teachers and staff do not see blatant insensitivity toward culture and race.

“I’ve never heard another student complain about a costume,” history teacher Sarah Carlson said. “There are a few that kind of give me pause, where I am an adult who is aware of the general larger cultural history that some of these stereotypes have, but I haven’t seen tons of stuff that concerns me.”

Some students, however, have felt a prevalence of the stereotypes in the society around them, particularly against certain cultural groups and ethnicities. Junior Douglas Curtis feels that the lack of attention paid to the discrimination caused by Halloween costumes further fuels already existing prejudices.

“I most often see this in the costumes of ‘pimps,’ which are most commonly worn by African-American males [as well as] depictions of Mexican rancheros as being drunk with gun holsters,” Douglas said. “[This] only does more to perpetuate society’s views on these races.”

However, from an adult perspective, students at our school are less aware of the gender stereotypes associated with costumes. What many see as a broader issue is the over-sexualization currently associated with most Halloween costumes on the market, especially those targeted at children and adolescents. The school minimally addresses this issue through enforcing dress codes, but the implied sexuality of certain costumes is harder for students to realize and pinpoint.

“I notice that students increasingly dress borderline inappropriate at school in general, in terms of sexualization,” English teacher Robert Barker said. “Even for really young girls, [the media] sells costumes that are sexualized versions of vampires and princesses. [The media] is not using that language, but it is very clear. It’s disturbing.”

Douglas, who cites films such as “Mean Girls” and more recent shows such as “Scream Queens” as major influencers on young girls especially, thinks that the media has caused gender stereotypes to skyrocket and creates a sort of peer pressure surrounding the dressing-up season.

“With a sexualized version [of every costume] presented to them in most every store, it is bound to happen that an impressionable youth will choose a revealing option,” Douglas said. “There is a strong edification that one must sexualize themselves on Halloween in order to fit in.”

While our school is generally aware of stereotypes, both regarding gender and culture, the media will continue perpetuating both kinds of stereotypes. Even after Ohio State university students conducted a nationwide awareness campaign in 2011 against Halloween costume stereotypes, a quick online search of “cultural costume ideas” today pulls up images of smiling non-ethnic models wearing cultural and gender stereotypes, such as the “sexy geisha” and the “Hey Amigo” costume. Many of Party City’s “funny costumes” include the same types of products, in addition to a large selection of “sexy” women’s and teen costumes.

“It’s not like Halloween is the only time girls are dressed up with the intention of looking sexy, I think it’s just everyone sees those costumes being sold in stores and it’s more shocking,” junior Sana Khader said. “But I don’t think that’s a problem in Halloween culture; it’s a problem in American culture.”

Much of this issue can be attributed to parents and families, who take the largest responsibility in informing students on what is appropriate to wear. When students are growing up in elementary and middle school, what their families deem appropriate helps shape their mindset for their high school years, especially in regard to early sexualization and educating minors on the topic. But aside from familial influence, the media dominates most of the other of student perceptions about dressing up, and so our community must stop its negative influence through increasing media awareness.

“I am a big critic of media, but I am also very critical of our abnegation of responsibility around being critical of media as individuals and not just taking a stance of, ‘You can’t do anything about it,’ as if you have no choice [but to accept the media’s influence],” Barker said. “If somebody still chooses to dress a certain way after educating themselves on media influence, to me, there’s something more respectable about somebody… making [their] own choices.”

The problem can also arise from an overall societal difficulty in discussing touchy subjects regarding sexual awareness and cultural prejudice with the youth, thus creating an overall lack of education and sending teenagers toward the media for confirmation.

“[There] is a taboo that surrounds the topics,” Douglas said. “In terms of sexualization, many are unable to talk freely with parents and authoritative figures about their feelings and desires toward sex… [Because of this], many [adolescents] seek outlets such as Halloween to express their sexuality because media and peers have already validated it as appropriate.”

The most effective way to approach this problem is for students to initiate the dialogue about stereotypes and media awareness. Only then will our school community begin to move past the continual, toxic stream of media perpetuation.

“[The school] will become a more authentic place,” Barker said. “It will become a place that is more independent in its thinking, which is the [most laudable] goal of education.”