Go Set a Watchman: a crude literary tchotchke

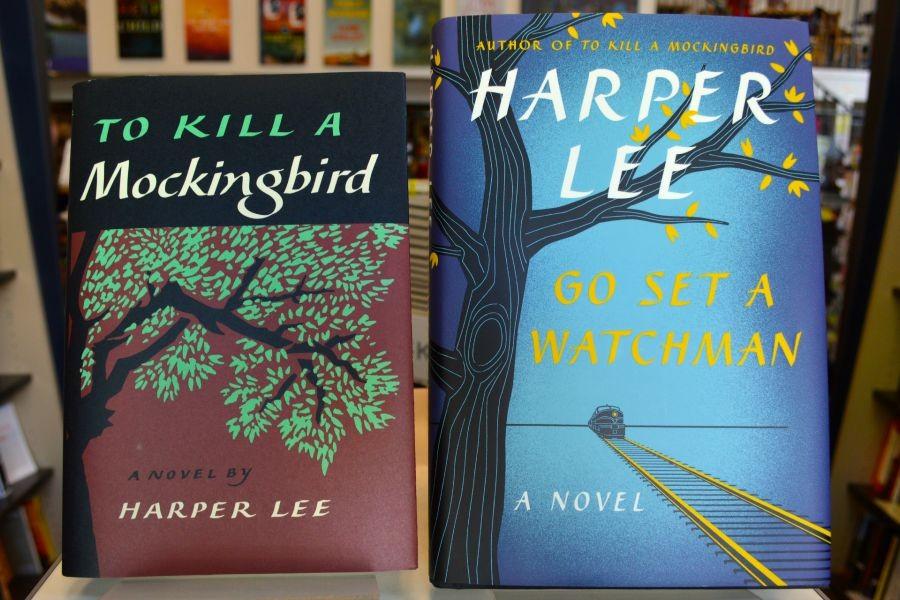

To the left is Harper Lee’s bestselling novel, To Kill a Mockingbird. On the right, her most recent book, Go Set a Watchman. Despite its brother’s success, Go Set a Watchman stands as little more than a first draft.

August 17, 2015

Breaking records for Harper Collins Publishing’s fastest selling title, Harper Lee’s new Go Set a Watchman has brought a mixed bag of reviews amidst the tumult of its publication. With the novelty of bestselling author Harper Lee’s first manuscript going to print, the commotion and excitement of readers around the world is not surprising.

Despite the manuscript’s commercial success, Go Set a Watchman only stands as a messy first draft and literary curio. Readers will wade through two hundred pages of unorganized plot to be disenchanted by the simple and unpersuasive answer to the very complex problem of disillusion and racism that Lee creates.

Alluding to deeper moral lessons, the novel’s four-word poetic title follows similar function to that of To Kill a Mockingbird. Just as To Kill a Mockingbird main character Atticus famously lectured his daughter Scout, or Jean Louise, and her brother on the virtues of the mockingbird, Lee blatantly reveals the meaning of the watchman.

“Every man’s island, Jean Louise, every man’s watchman, is his conscience. There is no such thing as a collective conscious.”

These words come from Dr. Finch, Jean Louise’s all-knowing esoteric uncle. They follow closely to the book’s theme of disillusion and bigotry, but more importantly show Harper Lee’s diversion from any meaningful conversation on civil rights. Dr. Finch’s lecturing words are not directed to Atticus, a segregationist at heart, but rather to Jean Louise, who holds dearly on to the ideals of racial equality.

While Go Set a Watchman’s message and theme is widely separated from equality, its plot is not. The crux is Jean Louise’s situation. She has grown up revering her father as the paragon of equality, justice, and moral integrity. As she returns to Maycomb from the progressive North at the age of 26, she suddenly realizes that he, just like Maycomb, is deep set into the segregationist views of the South.

Atticus is now a man once in the Ku Klux Klan and a staunch supremacist who asks, “Do you want Negroes by the carload in our schools…?”

In spite of probing conflict, the disconnect between the storyline and theme leads to a disappointing ending, with Lee failing to truly confront Jean Louise’s problems.

In the technical sense, the book doesn’t read as much more than a rough draft. The narrative throws itself backwards into Jean Louise’s childhood memories in tangents that are haphazardly dropped into storyline, and the multitude of extraneous character descriptions overburdens us. The first hundred pages sets up the idyllic Maycomb setting, but the host of problems the second half brings are barely resolved in a compressed ending. With a more distanced third person narration, Lee also loses what readers held so dear with To Kill a Mockingbird, the charming and intimately personal touch of Jean Louise’s innocence. The plot itself reflects how much Go Set a Watchman loses from cousin.

Still, Lee’s prose maintains some of her previous linguistic mastery. While set in the third person, Lee manages to aptly portray Jean Louise’s stream of conscious, and Jean Louise’s independent and strong willed personality does not fail to shine through. The dialogue, before the long tirades that crowd the second half, manages to illuminate the Southern dialect and flows naturally.

Go Set a Watchman, despite its failings as a novel, stands tall as a historical document. The new novel makes it easier to see the inner workings of Harper Lee’s mind and understand the stage out of which To Kill a Mockingbird was crafted. How a manuscript about a 26-year-old girl returning to discover her righteous father and loving husband’s racist views turns into the classic childhood novel of sweet innocence and moral justice is just one of many questions that arise. The world that Lee turned into the masterpiece of To Kill a Mockingbird is a starker and rougher setting in Go Set a Watchman that stands as a fascinating artifact of the past.

Go Set a Watchman is a different type of novel than most readers are used to, being crude and unpolished, a manuscript never meant to be published. For fans of To Kill a Mockingbird and curious readers, Go Set a Watchman is well worth the time. But for those wishing to sit back with a great read, the manuscript is a risky investment. As a rough and unedited story that has created a wave of new revelations and revealed disillusioned intentions, Go Set a Watchman stands more as a historical artifact than novel.