Follow the Fun — Or the Money

Talon writers explore the effects of profit-chasing on the quality of the traditional games industry

Expensive Advertising, Cheap Product

Reaching a worldwide revenue of nearly $100 billion, the games market continues to rise; it’s obvious why developers and publishers alike want a piece of the action. This desire to dominate the industry motivates companies to make the most impressive product possible in an attempt to capture a larger audience. At least, it did.

A trend has emerged over the recent years that indicates companies are putting more effort into selling games than making them. More money is spent on advertising some games than on developing them — sometimes up to twice as much. While this might reward companies with a boost in pre-orders, games that promise the most incredible experiences often set the bar too high for themselves, then suffer from negative reviews and a damaged reputation.

In 2014, Halo developer Bungie’s “Destiny” was hyped up until it was practically worshipped — all before its release. According to Bobby Kotick, CEO of the game’s publisher, Activision, “Destiny” had a total budget for development and marketing around $500 million, making it the most expensive game in history. However, the contract between Activision and Bungie indicates the large majority of the funds were spent on advertising. Incredibly, the game was profitable on the day it released.

Yet, audiences were crushed when “Destiny” failed to live up to its galaxy-sized expectations. Ships seen flying in trailers were actually static loading screens. It took years for custom matches, a staple of the “Halo” series, to be patched into “Destiny.” The best gear and cosmetics were locked behind a frustrating random number generator, leaving everything up to luck and making players’ efforts meaningless. Planets shown off in pre-alpha footage were cut before release, yet the game was oversaturated with expensive downloadable content. Destiny’s misleading marketing upset millions of players and shattered an entire fanbase.

The Ubisoft game “Watch Dogs” was a similar fiasco. Released on May 27 of 2014, the game is infamous for the graphical downgrades that took place before its release; Ubisoft enraptured gamers prior to release with beautiful gameplay footage, then delivered a game that looked far worse. Similar problems have arisen with other Ubisoft titles as well. Gamers feel betrayed when their purchase is nothing like what is shown in the trailers.

Many companies have not learned from these prior failures. The game “No Man’s Sky” caught everyone’s attention leading up to it’s release, yet now sits at a dismal Metacritic user score of 2.7 out of 10 on PC. Among other missing features, the lack of multiplayer may be the most shocking. Everything suggested “No Man’s Sky” would allow players to interact with one another across a procedurally-generated universe, from pre-release footage to the lead developer discussing the likelihood of players finding each other. After the game launched, a period of confusion was followed by the discovery that players could not see each other. It is hard to imagine why “No Man’s Sky” developer Hello Games failed to clarify the lack of multiplayer, a feature some imagined would be the core of the game.

To be fair, developers are probably not trying to lie or trick people into buying their game. They are proud of the technological advances they have created, and make claims based on what they hope to deliver. They are excited for their creation to be played, and want others to be excited as well. The issue comes into play when devs have to sacrifice content to prepare for release day. However, the bare minimum should be clarifying any announced content that will be cut, and a more ideal solution would be delaying the game to fulfill past promises.

While overhyping games is clearly a problem, the solution is more complex than one might think. Companies should be careful what they say before release. If they are sure a feature will be included, they have a viable reason to discuss it. However, selling a vision of a game not yet realized leads to severe consequences. Gamers should wait for reviews before buying games and should stop pre-ordering. If a future release is overhyped, developers’ hard work could still end in a “game over.”

Unfinished Games, Full Price

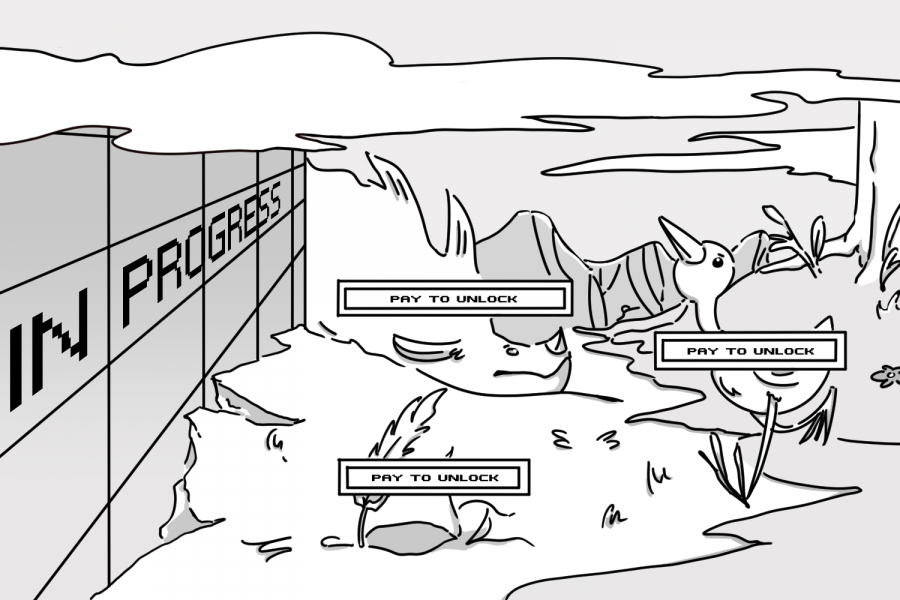

DLC, or downloadable content, has been around in video games for a while now. For a price, gamers could get an extra part of the game that hadn’t been available prior to release, giving them more content for them to play, and increasing the overall enjoyment of the game. Similarly, Steam Early Access, a program that allows consumers to play and fund beta builds of video games, started out with good intentions. However, developers have started using DLC and Early Access as an excuse to put out unfinished or incomplete games and run away with cash in their hands.

One egregious example of developers using DLC to make more money is Bioware’s 2012 game, “Mass Effect 3.” While generally praised by players, fans of the series criticized the game for locking a plot-essential character behind a $10 paywall. To make matters worse, the DLC was released on the first day, clearly to increase profits. Gamers were outraged, and some even went as far as to boycott Bioware entirely. Even with this controversy, though, Bioware grossed over $200 million from “Mass Effect 3,” according to their Q4 profit reports of that year.

Another example of poor DLC practices is “Battlefield 4.” The game offers an “Ultimate Shortcut Bundle” for $50, which allows players to unlock every weapon in the game at once. This business model is similar to that of many mobile games — allow the game to be played for free, and offer premium service for those who do not want to wait to have access to certain items or features in the game. “Battlefield 4,” however, is a $60 game, making it seem like a money-grubbing move. To top it off, some feel as if the game is purposefully trying to get you to shell out those $50 by making progress feel slow and unrewarding.

Many early access games can be found littered across the Steam Store, which has been the central hub for such games since it introduced the concept in March of 2013. There are a variety of reasons a developer might use Early Access, but the most notable reasons are that they don’t have enough money to continue development without the help of Early Access, and they want feedback on their game. One successful example is “Kerbal Space Program,” developed by Squad Games, whose frequent updates not only left the game feeling more and more polished as time went on, but also excited consumers, as content updates came regularly and served to keep gamers engaged and satisfied with the product.

Unfortunately, many other Early Access games don’t tell the same story. One such example is Doublefine’s “Spacebase DF-9,” which promised the opportunity to “Live amongst the stars”, and with the developer’s track record up to that point, consumers trusted that they would deliver on their promises. The game came out on Early Access on October 15, 2013, still marred with bugs and barely functional, without fulfilling the the aspects they promised. The developers attempted to update the game semi-regularly, but they were small and did not improve the disappointing experience. Then, out of left-field, Doublefine officially released the game on October 27, 2014, still plagued by the same issues it had before, and in May 2015, the publisher ceased all development of the game, leaving it broken and incomplete. Many gamers who bought the game were furious that Doublefine had seemingly deceived them, and the 78% disapproval rating on Steam only goes to show that.

Examples like these prove that it is imperative that consumers should stray away from games that use shady practices, and support developers like Squad Games, or CD-Projekt Red — makers of The Witcher 3, game which got lavish praise from critics and fans alike for its excellence in story and gameplay, and offered a $30 expansion pac which was praised for it’s excellence in quality in a scale comparable to the base game. While not all developers can compare to the DLC that the Witcher 3 has, the point is that it was a worthwhile experience for gamers. If we as consumers allow EA and other such companies to profit off incomplete games, it will slowly become the norm. We have the power to change the game industry with our own wallets. It’s just a matter of actually taking the steps necessary to accomplish that.