[dropcap]A[/dropcap]merican fashion, social cues and standardized testing: these are some among many cultural differences that senior Federica Cerruti learned to adjust to when she moved to Los Altos three years ago as a sophomore. Ethnically Italian, she was born and raised in France for seven years before moving to Japan and India for the next five years. She moved back to France at age twelve, where she stayed for two more years before moving to California when her father accepted a location transfer for his job at Tesla. She asserted that she resisted the urge to do assimilate, but that others in her family made an effort to blend in more.

“My little sister is an example,” she said. “When I came here, American style versus French fashion: two different worlds. I try to keep my foreign vibe and I don’t care if people here wear sweatpants – I’m not going to wear them. But my little sister, slightly younger, it was her way to become part of the culture.”

Growing up, Federica was raised in a culture that viewed fashion as more than aesthetics: it represents a dignified composure and a means of expressing sophistication. But she did acknowledge that environment influences its inhabitants, and that assimilating when it comes to visual appearances is perfectly understandable.

In addition to fashion, cultural social interactions were the most significant change and challenge that Federica had to adapt to. When she first moved here, she noted that the way people made friends and socialized was completely different than how she was accustomed to in France.

“Something that bugs me about American culture is that you don’t really know the hard line between friendship and acquaintance, which is something that is very clear in France,” she said. “There’s people you like, people you don’t know, and people that are your friends. And it’s really just clear, black and white lines. So for me it was really hard for me to find the social codes to make me feel a part of the high school and this whole community here.”

The somewhat hazy line between friend and acquaintance in America taught Federica different values of openness, as opposed to the less-friendly outlook that many European natives have towards foreigners.

“I would say America is way more open to the rest of the world,” she said. “If you go to France, and you’re a foreigner who doesn’t speak the language, you’re not really welcome; they’re not really going to be nice to you. They’re going to bark at you and speak to you in French and insult you if you don’t understand.”

She reasoned that this is due to the fact that it is geographically and historically a melting pot of different ethnicities and descents. In addition, she noted that when she moved to America, neighbors would quickly introduce themselves and lend a helping hand by helping the family adjust to the new community.

“In France, no one is going to come up to you and be nice just to be nice,” Federica said. “If you don’t like somebody, you’re not going to pretend and say that everything is great. So I actually appreciate that in the US, that people feel it’s important to be nice and welcoming even if they don’t get anything from it.”

Despite that Federica never felt particularly unwelcome in any setting, she was still bothered by some people’s response to her foreign background. When she first moved to the United States, she was frequently complimented on her accent, something that she initially took to be a compliment, but later disliked.

“I knew that they knew I was a foreigner, and to me, that’s weird, and I don’t like it,” Federica said. “It just makes me feel more like an outsider. When everyone speaks the same way and acts the same way, it’s not great to be that one person that just has a different accent.”

Other slightly uncomfortable encounters involved verbal communication, when she would occasionally mispronounce words. With shaky pronunciation, she found it stressful to constantly speak English, and was instantly put off when people would laugh, even if it was friendly. Though it was one thing for people to accept her for being culturally different, it was another to be called out for being audibly or physically different.

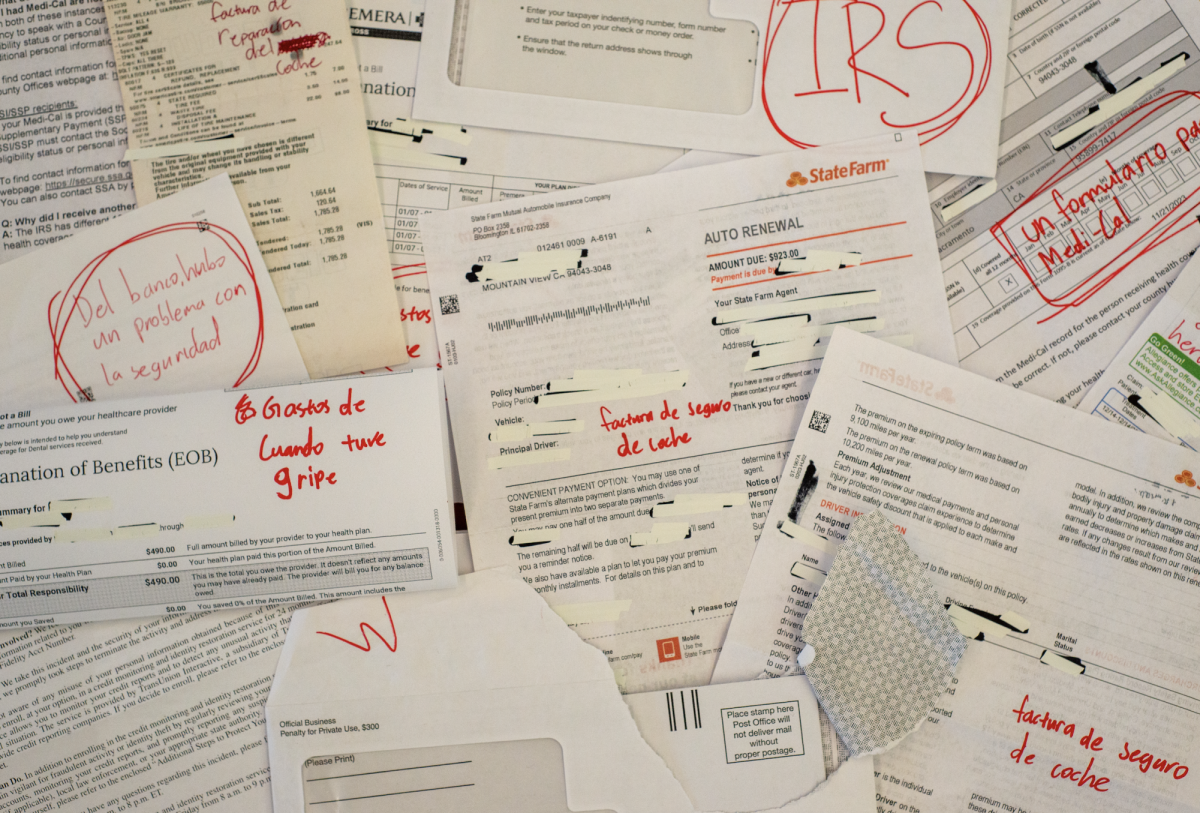

When it comes to academics, Federica faced one of the biggest cultural differences as she had to quickly adapt to standardized testing, something not very prevalent in the many school systems she grew up with.

“The first time I took the PSAT, I was like ‘what is this? What does this mean, what am I supposed to do?’” Federica said. “The whole idea of college applications was totally foreign to me, and that’s not how we do it in France. I didn’t know about essay processes and putting all this crazy work into something.”

In France, students take only one standardized test to enter a university, as opposed to the American way of receiving test prep and having the option of not only retaking certain tests, but to also take different tests like the SAT or ACT. However difficult the process of adjusting to these academic differences, Federica recognizes that the struggle made her a smarter and more resourceful person.

“I had to do way more things on my own when I moved here,” Federica said. “The European mindset is usually having the family really help the child through everything, and the child is slightly less independent. I was always held by the hand by someone else who showed me the way and explained different options for me, but here I had to look into SATs and AP classes on my own.”

Federica’s background is unique: having such an international life, she learned to quickly observe and blend different cultural behaviors to solidify her own identity and values.

“First-generations have to figure out things that a normal American teenager wouldn’t,” Federica said. “You have to be more smart about how you handle things, and so you gain a new perspective as a European-American.”