As social media feeds are increasingly flooded by political commentary and debates, political discussion has interwoven itself with entertainment and opinion. For many teenagers, that means encountering political content alongside celebrity gossip and TikTok dances while they scroll, reshaping how they interact with and respond to political news.

The recent assassination of political commentator Charlie Kirk has highlighted this phenomenon for many. The ubiquity of online political discourse is met with criticism from many students, even though most rely on social media for their news, according to a Talon survey. Regardless of their stance on politicized social media, students must learn to differentiate between fact and fiction. They must also decide how more explicit political stances by their peers, facilitated by social media, will play a role in their relationships.

Social media’s effect on youth political engagement

From campaigning to criticizing opponents’ viewpoints, politicians have taken to social media to convey relatable messaging to younger audiences previously inaccessible through traditional advertising.

A social media presence has essentially become a prerequisite for political success, as exemplified by California Governor Gavin Newsom streaming video games on Twitch, and President Donald Trump appearing on podcasts with internet personality Joe Rogan.

“I think it’s a good thing,” senior Jason Sellers said. “It gives younger generations who are future voters a perspective on who [political figures] are.”

However, experts in political communication have warned that politicized media feeds can amplify misinformation and polarization. According to the Pew Research Center, individuals who primarily obtain their news from social media tend to be less informed about factual developments and are more likely to encounter unverified or emotionally charged content.

This is in part due to the formation of algorithmic echo chambers that reinforce people’s political views.

“Online, everyone agrees with you because [social media creates] echo chambers,” senior Alice Marsot said. “This makes people more likely to express their political views over social media than in person.”

Such one-sided positive affirmation has negative effects.

“I feel like when people post about politics, they choose not to look at both sides of an argument,” senior Audrey Sanchez said. “They only look at their side.”

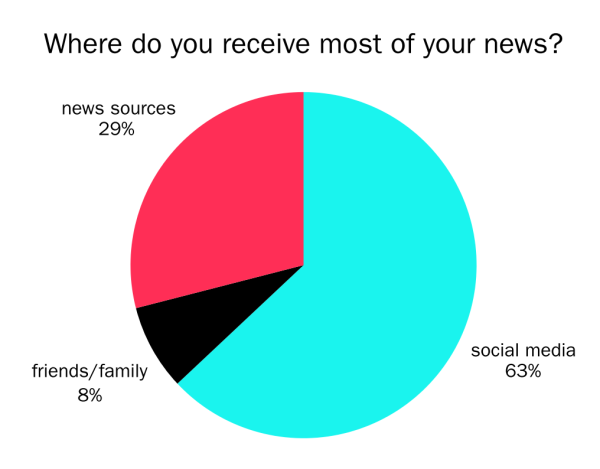

While almost all of the students The Talon interviewed expressed concerns about the issues that social media as a political medium presents, 63% of surveyed students said social media is their primary news source. This is compared to 29% from traditional news outlets and 8% from friends or family. The Talon conducted this survey on Instagram and received 325 responses.

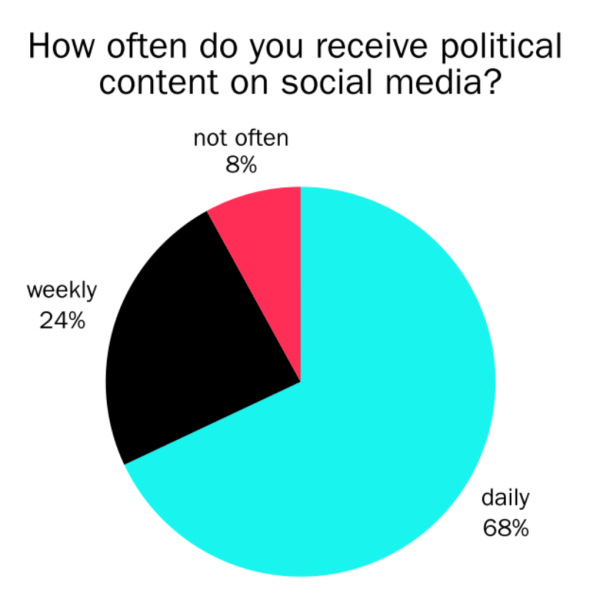

Love it or hate it, social media is a nearly unavoidable part of adolescents’ social lives, and political news is joining entertainment and opinion in teenagers’ daily digest.

Charlie Kirk as a microcosm

Within minutes of political commentator Charlie Kirk’s assassination at Utah Valley University on Sep. 10, videos of the incident and subsequent commentary were shared millions of times across social media, sparking polarized debate. This event demonstrated the speed at which political content circulates online and the prevalence of social media as a news network for young audiences.

Just like anything else posted on social media, political content is driven by virality — a metric quantified by likes and reposts, not veracity. Sensationalized political content reinforces binary narratives that drive polarization.

This has contributed to the rapid rise of political influencers like Kirk building large followings by producing short, high-engagement clips that capitalize on polarization and normalize harsh rhetoric.

“Teenagers are hearing extreme perspectives, and politics need nuance,” senior Serra Kozat said.

“I had an argument with my friend because I believed Kirk shouldn’t have been killed for what he was saying, and she did,” senior Alvin Roquero said. “I think it’s scary for people to get killed for their opinions.”

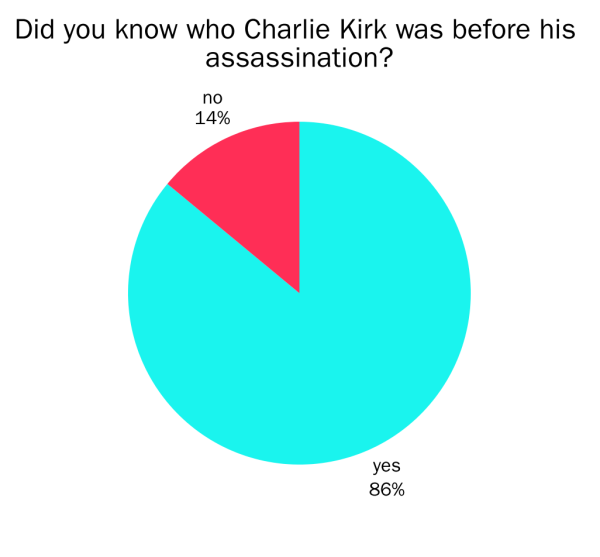

Kirk exemplifies the ubiquity of politicized social media feeds. Among surveyed students, 86% said they knew who Kirk was before his death. He’s a potent reminder of the need for media literacy to combat the rise of intentionally inflammatory content that doesn’t prioritize facts.

Consuming social media responsibly

With an increase in inflammatory content across the internet — some true, some biased and some entirely false — media literacy and fact-checking the news becomes even more important.

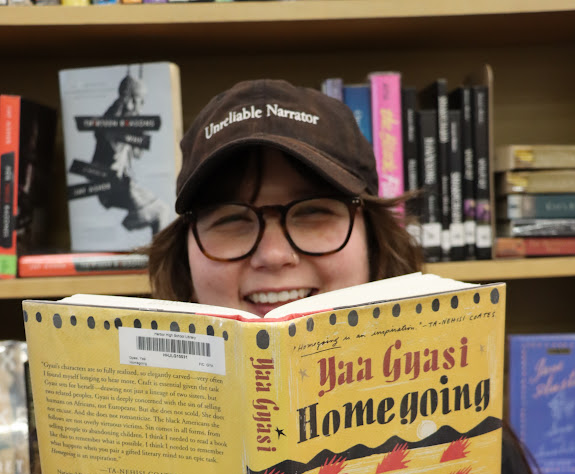

Librarian Gordon Jack believes that social media should not be a primary news source, given its “clickbaiting, polarizing” nature.

“If you’re only getting your news from your social media, you’re probably not getting enough news at all,” Jack said. “There’s a lot of clickbait there. People just notice the headline and scroll on, so it’s a very surface-level understanding of a story.”

Jack acknowledged that avoiding news on social media altogether is impossible, considering the prevalence of social media in students’ lives and its addictive, reaffirming algorithm. Rather, he said students can follow reliable news companies on social media as a first step in getting an objective, wider scope of information. He suggested the New York Times, NPR, New Yorker, Wall Street Journal and Daily Mail.

For students willing to further improve their news literacy, Jack encouraged downloading the New York Times app — which all Los Altos High School students have a news subscription to — and turning notifications on.

Similarly, social studies teacher Roger Kim said he teaches students to not only fact-check news stories, but also to read the same stories from other points of view

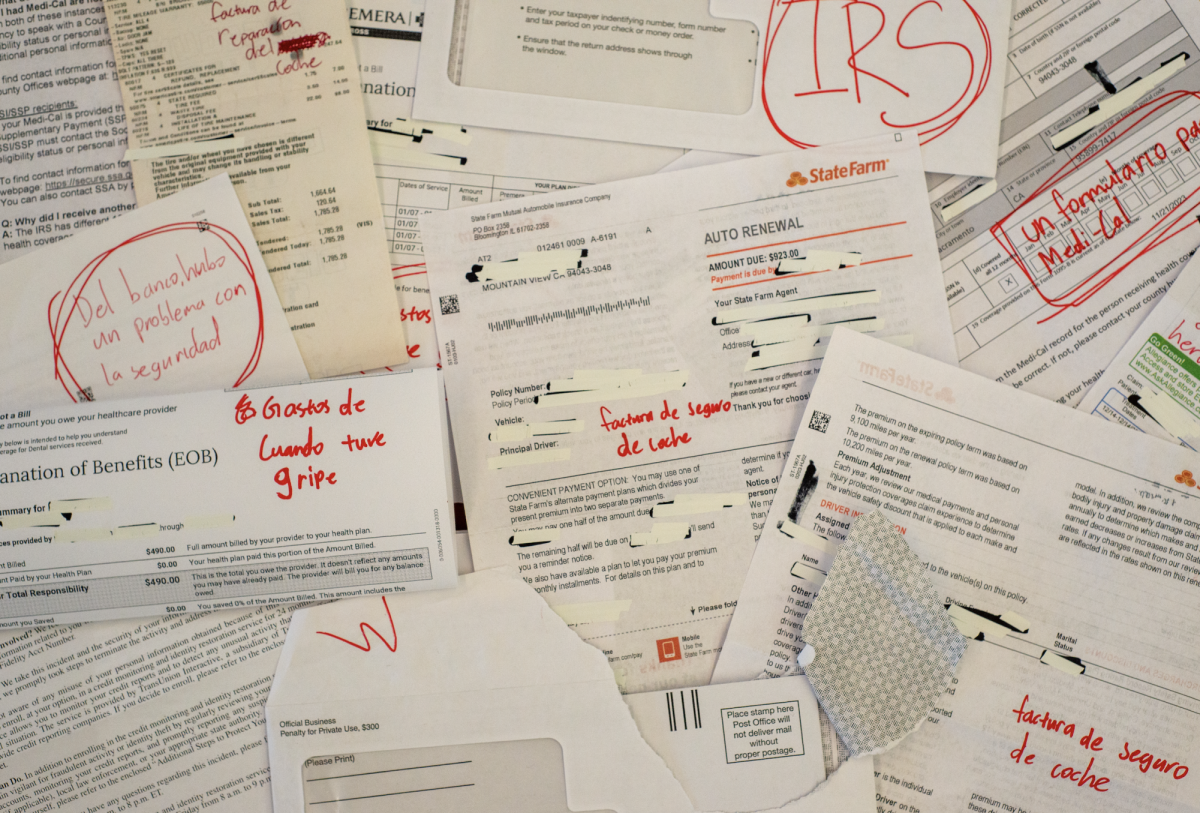

“When I taught Ethnic Studies, many of the sources students cited were from podcasts and social media — Ben Shapiro, Charlie Kirk,” Kim said. “I want them to question everything — their sources, what media they consume, what biases they have and what alternative viewpoints are out there.”

While reading the news or consuming content himself, Kim said he always tries to corroborate stories before he believes them, and advised students to do the same.

“In history, we teach that one source does not prove anything,” Kim said. “Multiple sources must corroborate each other, and that’s what I hope students can do and will do.”

Politics on social media affecting relationships

Not only does social media amplify attention-grabbing political content for teenagers to consume, they have also made it easier than ever for teenagers to share — and be judged — for their own beliefs. This dynamic pushes teenagers to decide how much political difference they’re willing to tolerate in friendships.

For some, it’s a non-issue.

“The political party that people belong to doesn’t matter to me,” junior Ceana Oh said. “When we’re just friends, it doesn’t matter to me what they believe.”

For others, it’s a factor they seriously consider in navigating relationships, whether it raises an eyebrow or is a full dealbreaker.

“I wouldn’t say people’s posts affect whether or not I’m nice to them, but they definitely affect whether or not I respect them,” Audrey said.

“Politics is definitely something I would end a friendship over because it heavily details what kind of person you are,” senior Luca Ferrari said.

Closing thoughts

Teenagers aren’t just the audience of political media — they are its participants and amplifiers. In a world where algorithms learn to understand our political preferences better than we do, staying informed requires more than simply seeing both sides of an argument. The future of online political discourse doesn’t just depend on which political figures have the biggest platforms, but on how we choose to use and interact with ours.