I’ll never forget overhearing one of my teachers on the phone, his voice low but his words unmistakable: “These gay kids seriously need to seek counseling from a pastor or something! A purely atmospheric problem can definitely be fixed.” Witnessing that wasn’t just unsettling — it was a bitter reminder of how deep-set misconceptions about our generation are.

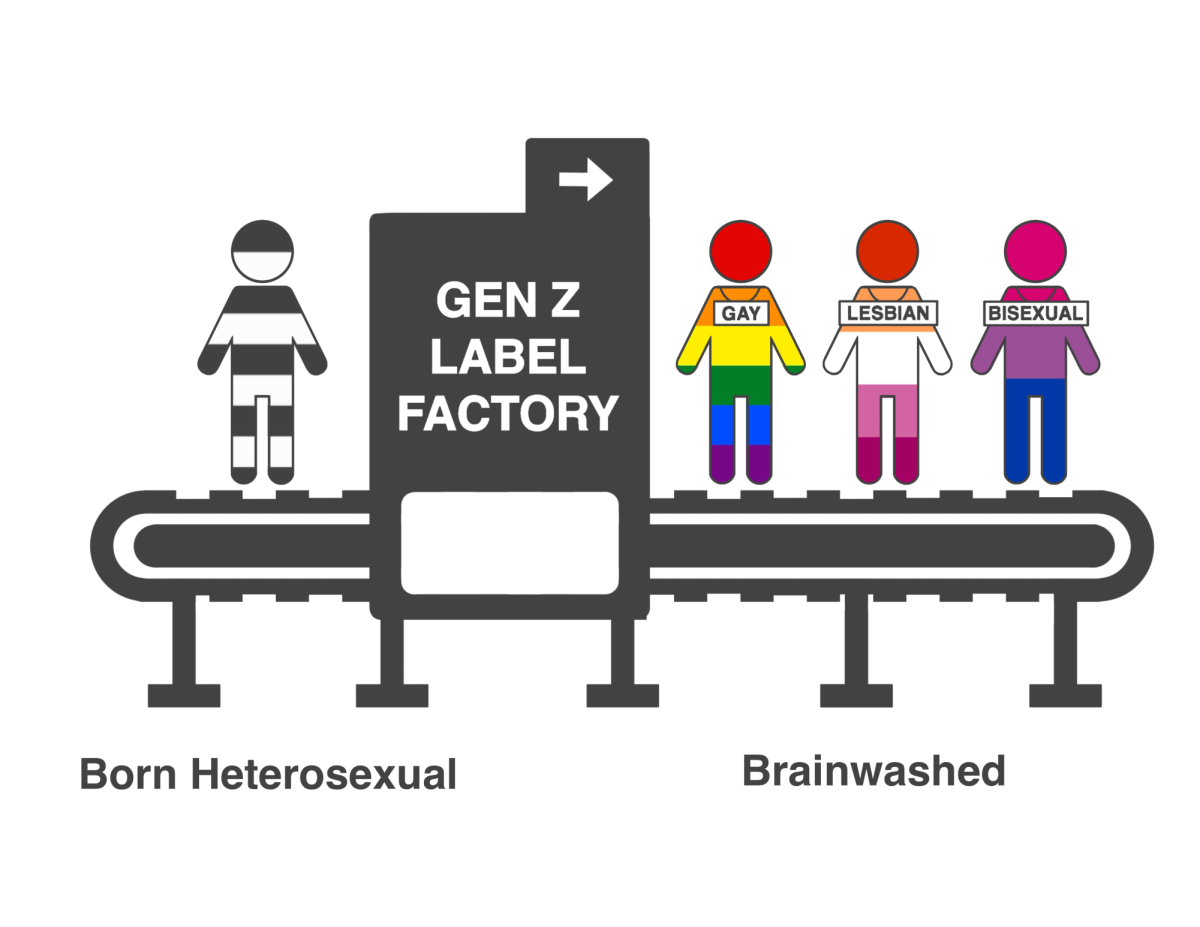

In the ongoing culture war over gender and sexual identity, one accusation hurled at Gen Z stands out to me for its sheer absurdity: the idea that young people are “brainwashed” into identifying as queer. This narrative argues that TikTok algorithms, liberal teachers, and rainbow capitalism have joined forces to manufacture an army of LGBTQ+ youth. But the “logic” behind this claim crumbles under basic scrutiny.

Surveys do show that Gen Z has a higher percentage of people identifying as LGBTQ+ than any previous generation. In 2023, Gallup reported that about 22.3 percent of Gen Z identified as non-heterosexual, compared to just 2.3 percent of Baby Boomers. This isn’t evidence of some covert indoctrination campaign, however; it’s just proof that ingrained social stigmas are finally starting to wear away.

For centuries, being queer wasn’t just stigmatized — it meant losing one’s job, one’s family, or even one’s life. During the Nazi persecution of homosexuals, an estimated 5,000 to 15,000 homosexuals were subject to inhumane medical experiments in concentration camps and left to die. Just a few years later, the Lavender Scare resulted in tens of thousands of gay workers being publicly humiliated and losing their jobs. Only until 1973 was homosexuality no longer considered a mental illness.

It wasn’t that fewer queer people existed before — only that fewer felt safe enough to say so, or have the opportunity to become aware of it themselves. The destigmatization of queerness through culture and media certainly plays a major role in the 20 percent difference between generations, but this doesn’t mean Gen Z is “converting” straight people into queerness. They’re simply the first generation to live in a culture that encourages authenticity.

Much of the backlash stems from a misguided belief that being queer is a choice. This argument, which has been used to justify discrimination for decades, claims: “if it’s a choice, then it’s fair to criticize — or even try to change it.” The main issue with this assumption is that it conveniently ignores both the intrinsic nature of one’s identity as well as the actual lived experiences of LGBTQ+ people.

People don’t wake up one day and suddenly decide to be queer. Human identity is far more nuanced, shaped by a complex interplay of biological and environmental factors. Studies suggest that genetics, prenatal development, and even hormonal exposure can all play a role in determining one’s sexual orientation or gender identity.

Our environment matters too. People raised in open, supportive households are more likely to have the freedom to express their identity. Conversely, in environments where queerness is stigmatized, people may feel forced to suppress parts of themselves. This is why some people don’t “realize” they’re queer until adulthood — they may have been taught that queerness was unacceptable, if they heard of the concept at all.

That being said, these environmental factors — exposure to inclusive language or representation — are not equivalent to brainwashing. Brainwashing implies coercion and manipulation in an effort to replace someone’s original beliefs with new ones. Providing context for individuals to better understand innate parts of themselves isn’t that. The inclusivity of this generation doesn’t dictate identity, but rather, creates an environment where self-discovery can thrive.

If anything qualifies as brainwashing, it’s conversion therapy — touted as a “solution” by some, with a sole purpose of forcibly changing someone’s identity. Research has consistently shown that conversion therapy is not only ineffective but also causes significant psychological harm, including increased rates of depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation.

The uncomfortable truth behind the “brainwashing” rhetoric is that people often use it as a smokescreen for anti-LGBTQ+ bigotry. Many who claim to only oppose “brainwashing” rarely display any outrage over actual coercion — like forced heterosexuality or gender roles. By targeting queerness as something that people are “turned” into, these critics reduce LGBTQ+ identities to something inherently undesirable — a problem to be solved rather than a valid expression of human diversity. But if queerness were truly an unnatural force that corrupts an otherwise “normal” identity, wouldn’t past generations — who actively suppressed it — have succeeded in erasing it?

This idea that there are “normal” and “abnormal” identities is rooted in binary thinking. Queerness exists on a spectrum, with few people landing 100 percent at one extreme or the other. Discovering one’s identity is not so much about immediately finding a fitting label; more importantly, it’s about being allowed the space to explore without fear or judgment. Some people may experiment with labels before finding the one that feels right, and others might not feel the need to label themselves at all. That doesn’t make their experiences less valid — it’s what makes them human.

This shift in perspective is what sets Gen Z apart. The rise in LGBTQ+ identification is not a rush to forcibly identify as queer, as critics claim, but a collective understanding that the spectrum of human identity is broader, more fluid than we’ve historically acknowledged. Growing up in an era of open conversations and an unprecedented access to information, Gen Z has been able to question binary thinking without the same level of pushback found by previous generations. Those who identify as queer did not suddenly choose to “become” queer — they’re simply better equipped to articulate who they’ve always been.

So no, Gen Z isn’t being indoctrinated into queerness. They’re breaking free from a history of extreme prejudices. And if that makes some people uncomfortable, it’s worth asking: is the problem really Gen Z, or a society that’s still struggling to let people be themselves?