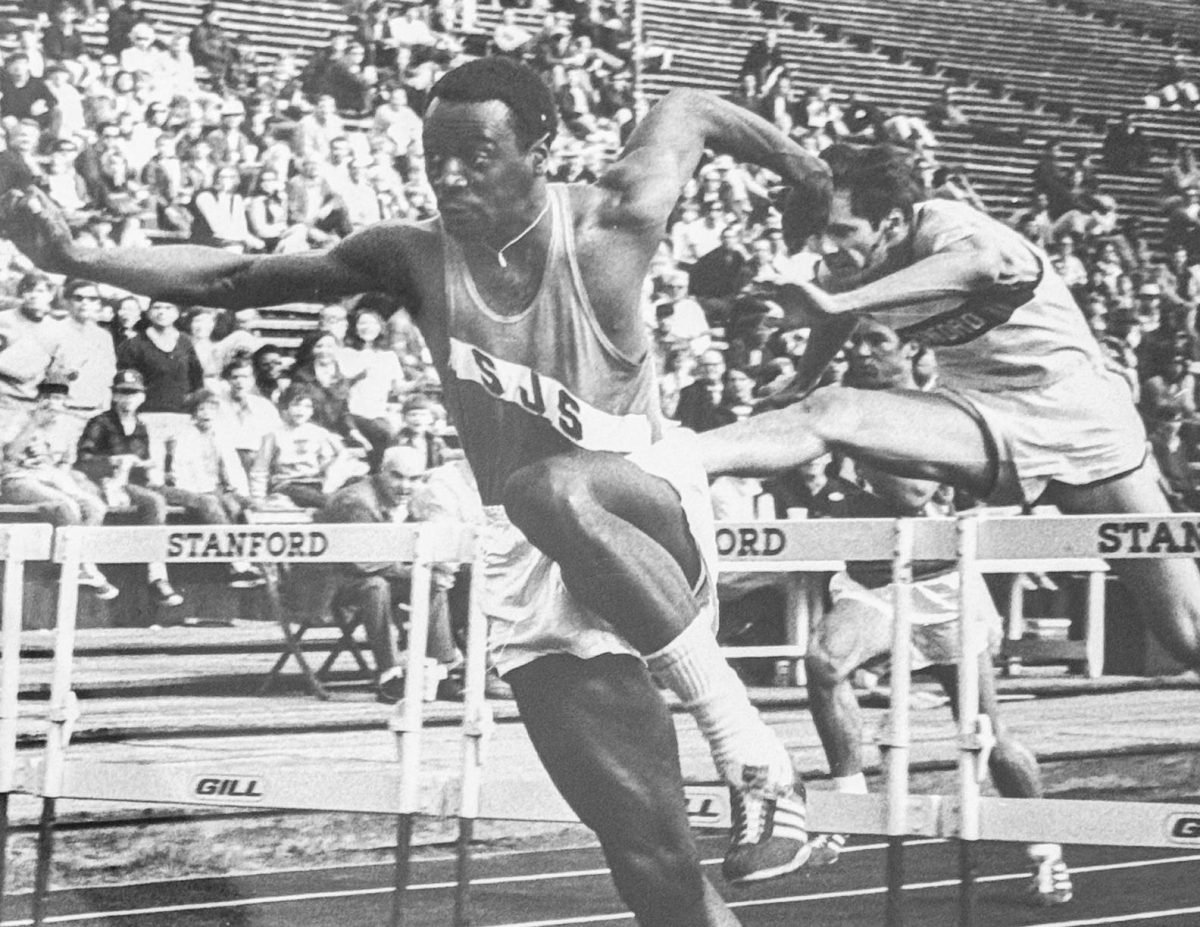

Hurdles Coach George Carty has been running since he could walk. His passion and dedication gave him life-changing opportunities, including winning an NCAA Championship with San José State University, Olympic training, and a platform to speak on human rights.

In kindergarten, Carty was already getting onto tracks to run with high schoolers. Despite his young age, he was fast from the start. It wasn’t until the other kids began catching up that he found his love for hurdles — or for Carty’s first few years, trash cans turned on their sides. With enough practice, Carty was competing in high school hurdle events by seventh grade.

“The only thing important to me was running track for school,” Carty said.

But he always had an appetite for more. With his spark and speed, Carty put up Olympic level trial times as a junior in high school. In 1964, Carty traveled to Rutgers University N.J., and Randall’s Island, N.Y. for the Olympic Trials.

“If you can beat the kids in New York, they’ll love you,” Carty said. “That’s what kept me going.”

His success brought him to the Pre-Olympic team in 1968, which trained rigorously in South Lake Tahoe, roughly 6,000 feet above sea level. Since they were the first team to train at such a high altitude, health concerns arose for the Black team members, according to Carty. He recalled that their cells weren’t getting enough oxygen, and as a result, ambulances were often kept nearby to accommodate them after a run.

While in Tahoe, Carty trained with some of the best runners in America. They learned from each other by sharing strategies, and their times began to drop. They traveled all around North America for meets, and the altitude training ultimately enhanced their training and performance.

But with every physical challenge that comes with being a good athlete, mental battles persist, too. In his trials, Carty was placed in an uncomfortable lane position. According to Carty, the lack of familiarity and comfort was difficult for him to overcome.

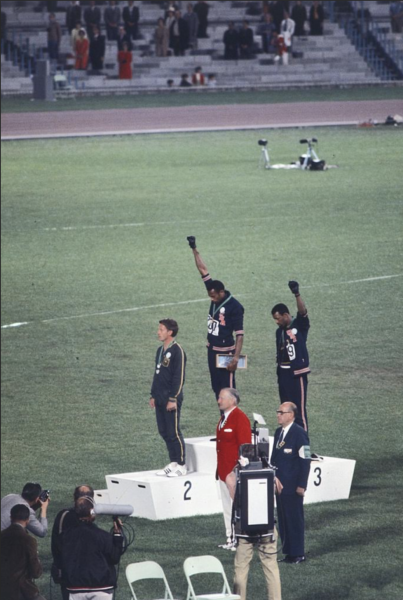

But beyond being a top-ranked runner, Carty was also a strong advocate for human rights. On the 1968 SJSU track team, Carty and his teammates were radical and outspoken about human rights, often protesting through their clothing by wearing buttons to support the Human Rights Project. Carty’s teammates — John Carlos from SJSU, Tommie Smith from the Bay Area Striders track club — famously raised their fists in support of the civil rights movement on the podium of the Olympics.

in support of civil rights during the 1968 Mexican Olympic Games. (Angelo Cozzi via Wikimedia Commons)

Their activism and athletic talent drew large crowds — over 20,000 people once watched them race at Stanford University, one of the schools Carty enjoyed competing against. Carty and his teammates were leaders in the Black Power movement, fighting for racial pride, equality, and human rights.

“America’s about everyone getting together with peace and harmony,” Carty said. “So, they either liked us or hated us — there was no in between.”

Alongside their public activism, the SJSU team reached its pinnacle at the 1969 NCAA Championships. However, as Carty recalls, the meet went far from smooth — he and his teammates placed much lower than expected.

“It was hard to explain,” Carty said. “All of us choked.”

But despite the subpar individual performances, the team came together to win it all.

“It was crazy,” Carty said. “We won it and thought, maybe it’s just supposed to be.”

Roughly 30 years later, Carty finally made his way to Los Altos High School, brought by Hurdles Head Coach Robyn Hughes. After the school he previously coached shut down their track program, Carty — who was coaching both teams at the time — simply stayed at Los Altos High School. At Los Altos, Carty emphasizes the importance of putting in the work to his athletes, and often coaches hurdlers who make the State meet and hurdle in college.

“You’ll always remember your success,” Carty said. “Because I’ll be passed on, but you’ll remember what you did, and nobody can take that from you.”