At the Cantor, “Spirit House” and “Livien Yin: Thirsty” explore Asian American identity

CANTOR, STANFORD — I knew next to nothing about Thai funeral customs, paper sons and daughters during the Chinese Exclusion era, or incidents of racial violence against Asian-Americans during 1982 when I came to visit the Cantor. Still, the works at “Spirit House” and “Livien Yin: Thirsty” were so visually compelling that they could be understood deeply and bodily, without a prior basis of historical knowledge. I felt a quiet pleasure in not knowing about these stories, and in discovering them through aesthetic experiences alone.

At the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University, a day spent wandering through “Spirit House” and “Livien Yin: Thirsty” feels like stepping into a liminal world of contemporary Asian-American art: at “Spirit House,” viewers glide through a past of Asian-American violence, subjugation, and resilience. Meanwhile, Livien Yin’s paintings unfold Chinese-American history in lucent, incandescent colors, as if glowing through a tinted glass.

Both galleries contemplate the implications of past events upon the present and future. And both are part of Cantor’s Asian American Art Initiative — co-founded and co-directed by Marci Kwon and Dr. Aleesa Pitchamarn Alexander — in which curators cultivate dialogue around Asian American history, through art and artistic spatiality.

“You can never replicate the experience of going to a museum,” exhibition curator Dr. Aleesa Pitchamarn Alexander said. “There’s something about physically being in a space that possesses history — and holds objects with historical and aesthetic value — that provides this kind of quiet space of reflection and introspection.”

There really isn’t anything like it: neither the space of the museum nor the fundamentally exploratory nature of visiting. Alexander also dispels the idea that visitors need extensive knowledge in order to engage with the art.

“You can have whatever experience you want,” Alexander said. “You can treat a museum as a space to reflect and encounter things that you can’t encounter anywhere else. If you just want to stare at the surfaces of Livien Yin’s paintings, because they’re so textured and beautiful, you should just do that, you know?”

“Bring yourself as you are, be open to the experience,” Alexander said. “Don’t feel intimidated by it. And embrace the fact that there is no other space like this, and hopefully, you’ll find something that speaks to you.”

“What does it mean to speak to ghosts, inhabit haunted spaces, be reincarnated, or enter different dimensions?” ~ Aleesa Pitchamarn Alexander, “Spirit House”

“Spirit House” invites visitors into a liminal space where Asian American artists grapple with the unseen, spectral, sacred parts of the supernatural world. The exhibition is open from Wednesday, September 4 to Sunday, January 26, and comprises nearly 50 works of art from 33 artists.

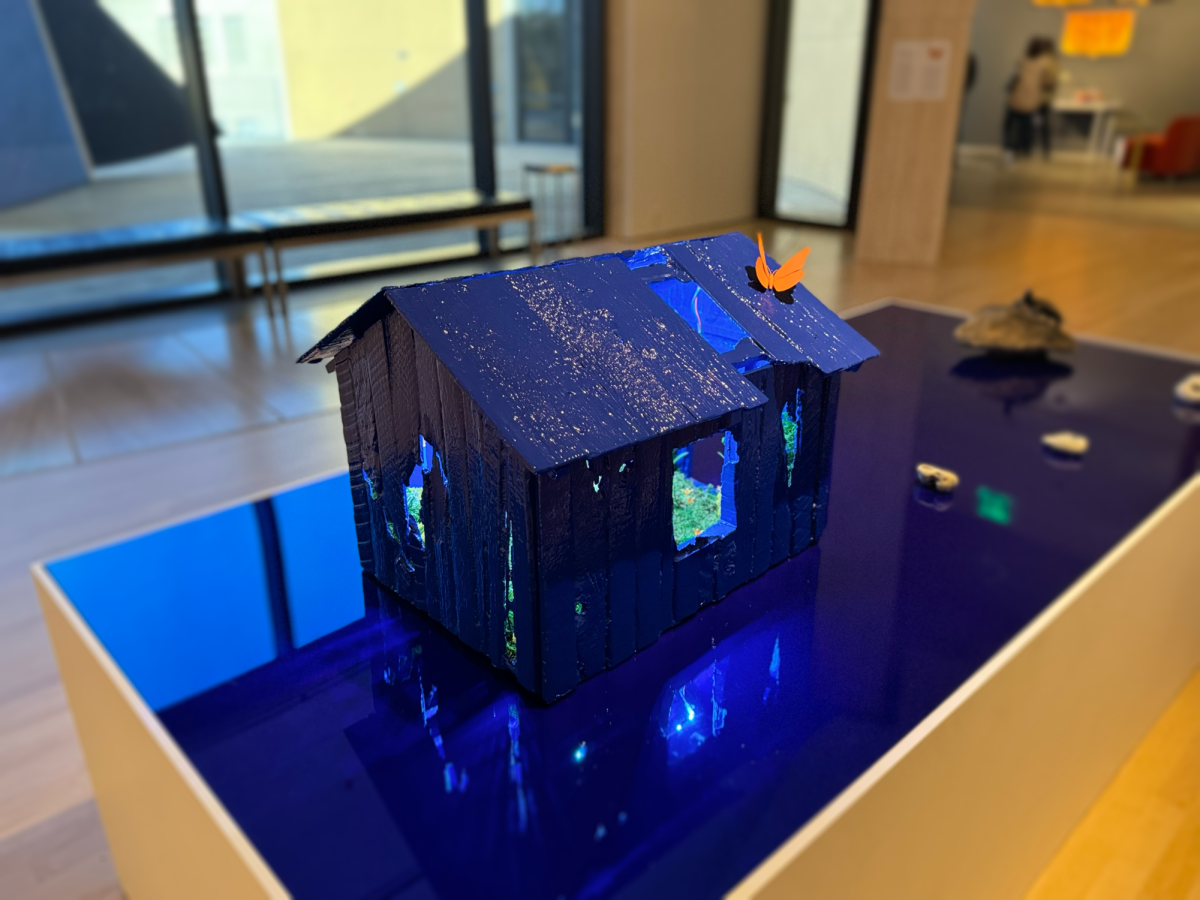

Art becomes a vessel for ancestral, spiritual, and haunted experiences at “Spirit House.” The exhibition draws from Thai spirit houses — small devotional structures that provide shelter for guardian spirits — and uses art to bridge the gap between the living and dead. These pieces act as conduits for spiritual expression, tying family histories disrupted by war, migration, and generational trauma with contemporary stories of resistance and refusal.

“‘Spirit House’ is a show about asking difficult, interesting existential questions,” Alexander said. “Like: ‘What does it mean to live a meaningful life?’ And ‘What do we do with the time that we have on Earth?’ These are life questions for all of us, not just Asian Americans.”

The exhibition is split into five sections: Spirit Houses, Ghosts, Hauntings, Shrines, and Dimensions. The gallery unfolds progressively, beginning with Spirit Houses to ground visitors by emphasizing relationships between people and the spaces they inhabit.

Then the exhibition shifts to Ghosts, which discusses the ghosts — secrets, memories, and taboos — that haunt diasporic families.

“Ghosts is really about personal narratives,” Alexander said. “I’m asking you to think introspectively about yourself as an individual, and also in relation to others.”

As the exhibition expands into Hauntings and Shrines, the scope and perspectives of the works expand, too.

“In Hauntings, I want you to think about yourself within a global, interconnected perspective — perhaps of loss and violence — especially because so many artists are refugees,” Alexander said. “And so, we think about how history is not an abstract concept, but a real thing that we embody.”

The final section — Dimensions — explores the “cosmic” implications of oppression and refusal; Alexander describes the exhibition as “progressively unfolding from place to the cosmos,” as historical events become “incarnated in multiple lifetimes and forms,” blurring chronologies across history and time.

Alexander found inspiration from her upbringing in Bangkok, where she remembered how spirit houses were “these portals to another dimension, allowing you to speak to the dead, to engage with the supernatural and ritual.” Alexander combined these memories with a recurring thematic trend of inheritance, migration, familial struggles, and spiritual contemplation she noticed during studio visits with artists.

“Between some of these artists, they are making work that has this shared visuality, and that is significant and powerful,” Alexander said. “But I also wanted people to see that our experiences are also diverse and particular. We are honoring the individual, because we Asian Americans are not a monolith and because each of these artists has had very particular experiences and perspectives on those experiences.”

For Alexander, each artwork collapses the spatiality between the physical and spiritual world, and manifests the traumas that haunt Asian-Americans, like ghosts.

“I feel like all of these works of art were spirit houses in their own right,” Alexander said.

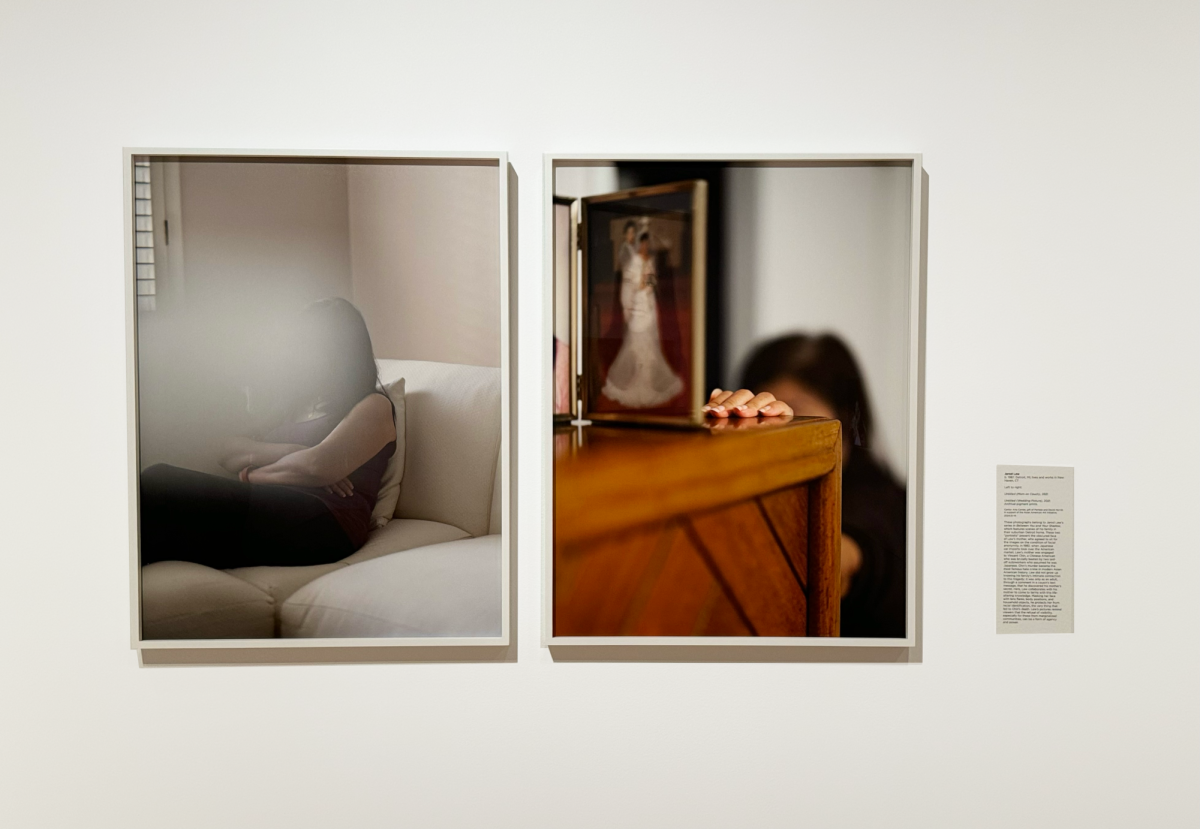

“Untitled (Mom on Couch)” and “Untitled (Wedding Picture),” are part of Jarod Lew’s photographic series titled “In Between You and Your Shadow.” These photographs feature Lew’s mother, who was engaged to Vincent Chin (a Chinese American killed in one of the most infamous Asian-American hate crimes), and depict Lew’s mother obscured behind household objects and lens flares

Lew sought to give dignity to his mother through art. His photographs depict his mother obscured behind household objects and by lens flares — “not so much a ghost, but in the realm of the ghostly,” as Lew describes — as if she were a giant mythical sculpture obscured by fog.

Lew considered turning his mother’s head away, or using her hands to hide her face, but eventually decided to use lens flare to create a more interesting image.

“I wanted something more ethereal and mystical, and maybe even more magical, to unveil itself in the photograph,” Lew said.

For Lew’s mother, obscurity and the intentional refusal of visibility can be empowering and liberating, hence the concealment of his mother’s face.

“If my mom’s wishes were to not have her identity shown, and not to be associated with Vincent Chin and this history, then it is empowering for her to have that control in her own life, and over who she is as a human being,” Lew said. “I wanted to use that refusal as a way to speak to her right for her own opacity and the right for what she wants the public to know about her.”

In “The Accusation,” Chinese-Malaysian and Mexican artist Timothy Lai imagines a quintessential father and son: the father faces his son, who stands on a stairway and crouches to receive a lesson — or an accusation. A strand of tiny walking figures connects the father’s mouth to his son’s ear, “symbolizing the oral histories, narratives, and anxieties often passed from parent to child,” Lai describes.

His goal was to “complicate the hierarchical positioning of their relationship,” Lai said. Though the father possesses higher authority and influence in familial relationships, does the father possess more patriarchal influence in the family? Or is it the son — who he has raised, who embodies the family’s future and their hopes for upward mobility?

“A lot of people I knew grew up hearing phrases like, ‘I do this so you can have a better life,’” Lai said. “That’s sort of where that idea started from.”

A triptych, by Vietnamese artist Binh Danh, comprised of: “The Botany of Tuol Sieng Genocide Museum #1,” “The Botany of Tuol Sieng Genocide Museum #2,” and “The Memory of Tuol Sleng Prison, Child 9.” Dan uses chlorophyll printing to photosynthesize, on leaves, images of people who were tortured and executed during the Cambodian genocide. For Danh, he hopes that when viewers see these works, the unidentified victims captured in the leaves are reincarnated in the present, so that “the dead are able to live for a time in our minds and be part of the material world.”

In “The Shrine,” Nina Molloy portrays her great-grandfather, grandfather, and mother as translucent, ghost-like figures, blending into surrounding objects. Drawing inspiration from Southeast Asian cultural elements, Molloy is evoking both nostalgia and religious ecstasy in her painting. She incorporates the density from Dutch altar painting, the flattened perspective from Korean chaekgori, and the structure of Thai Spirit Houses, using art to transcend generations, time, and memory.

Lien Truong’s “The Crone” is part of her series on female archetypes, where she depicts her grandmother as a powerful Crone — a mythical figure known for her independence and refusal of patriarchal norms. Based on the only surviving photograph of her grandmother, who died during the French occupation of Vietnam, the painting contrasts her youthful face with aged hands, thereby representing an unfulfilled future. Truong remimagines her grandmother as a “powerful figure, able to defy time and space and speak to her family’s future”.

“Livien Yin: Thirsty” marks the debut solo museum exhibition for Brooklyn-based artist Livien Yin, and is on view from Wednesday, August 21 to Sunday, February 2. The exhibition, held in a single gallery, offers an intimate exploration of Asian-American Identity. Through depicting contemporary scenes along with historical figures, Yin connects Asian-Americans with different generations.

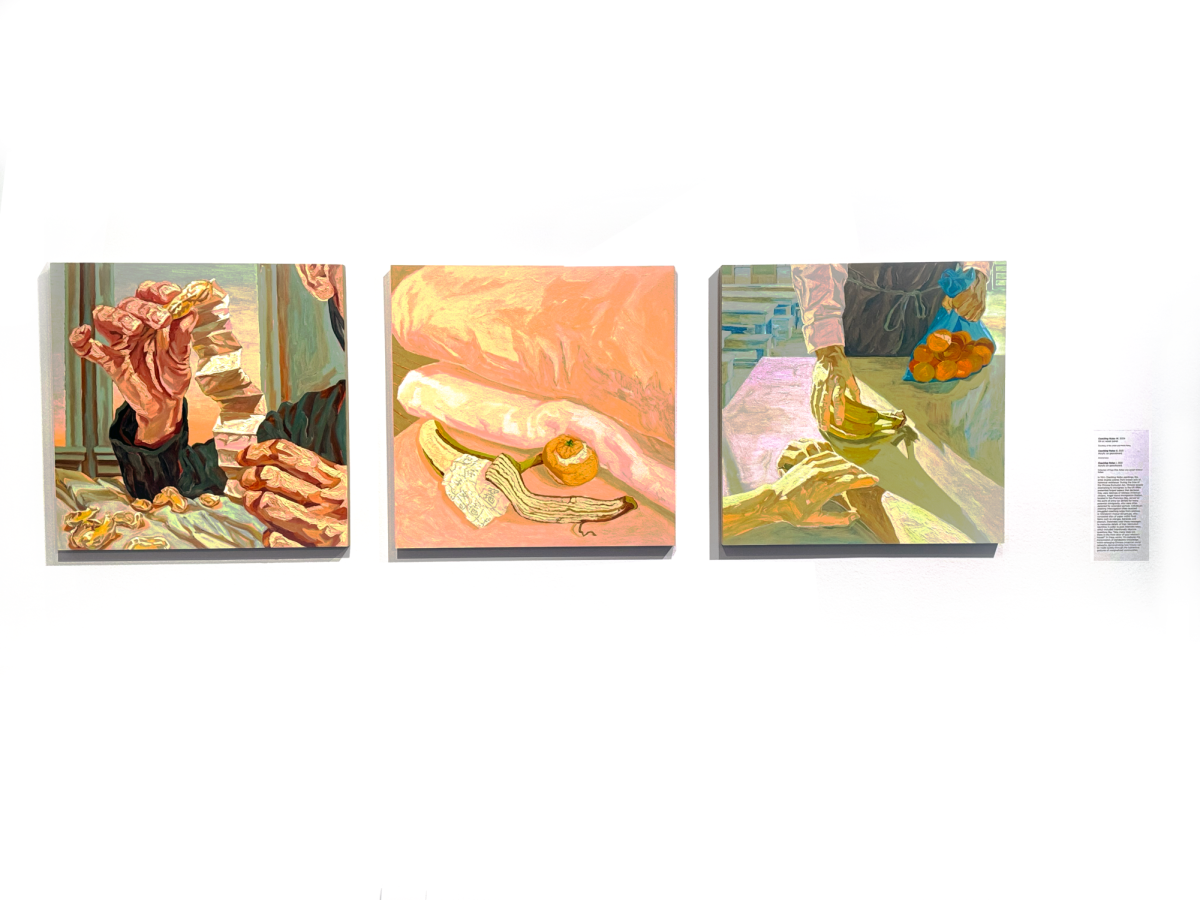

The two series of works in the gallery, “Paper Suns” and “Coaching Notes”, focus on Asian-American resistance during the Chinese Exclusion Act.

Describing the experience of “Paper Sons and Daughters” — Chinese Americans who, to circumvent the Chinese Exclusion Act, assumed false identities to gain entry into the United States — Yin explains: “They had to memorize extensive details about their new fake identities, like the village map of their supposed ‘hometown,’ or what their cousins’ names were.” As immigrants awaited processing at Angel Island, Chinatown aid groups and relatives would secretly provide them with “coaching notes”: documents that contained details for passing interrogations.

For Yin, the lack of visual, material records caused them to want to capture and immortalize the exchange of coaching notes.

“There are some records of coaching notes themselves, but the act of passing along these notes was not photographed, and therefore not visually accessible to us,” Yin said. “That made me want to visualize something that we cannot see. By wanting to see this history, and creating this fictional scenario of it happening, it’s a process that makes that history more real to me.”

However, Yin’s work doesn’t focus solely on hardship. Instead, she sought to subvert patronizing narratives surrounding the Chinese Exclusion and highlight resistance — through their work, they make invisible resistance visible.

“‘Paper Suns also expands the history that I inherited earlier on, which was a more ‘passive’ history of the Chinese Exclusion Act,” Yin said. “The language around it would victimize the Chinese immigrants — but alongside this marginalizing history, there’s also the lesser known stories of people’s agency and ingenuity around the Chinese Exclusion Act, of Asian-Americans going around loopholes that were put in place by the law for largely racist and classist reasons.”

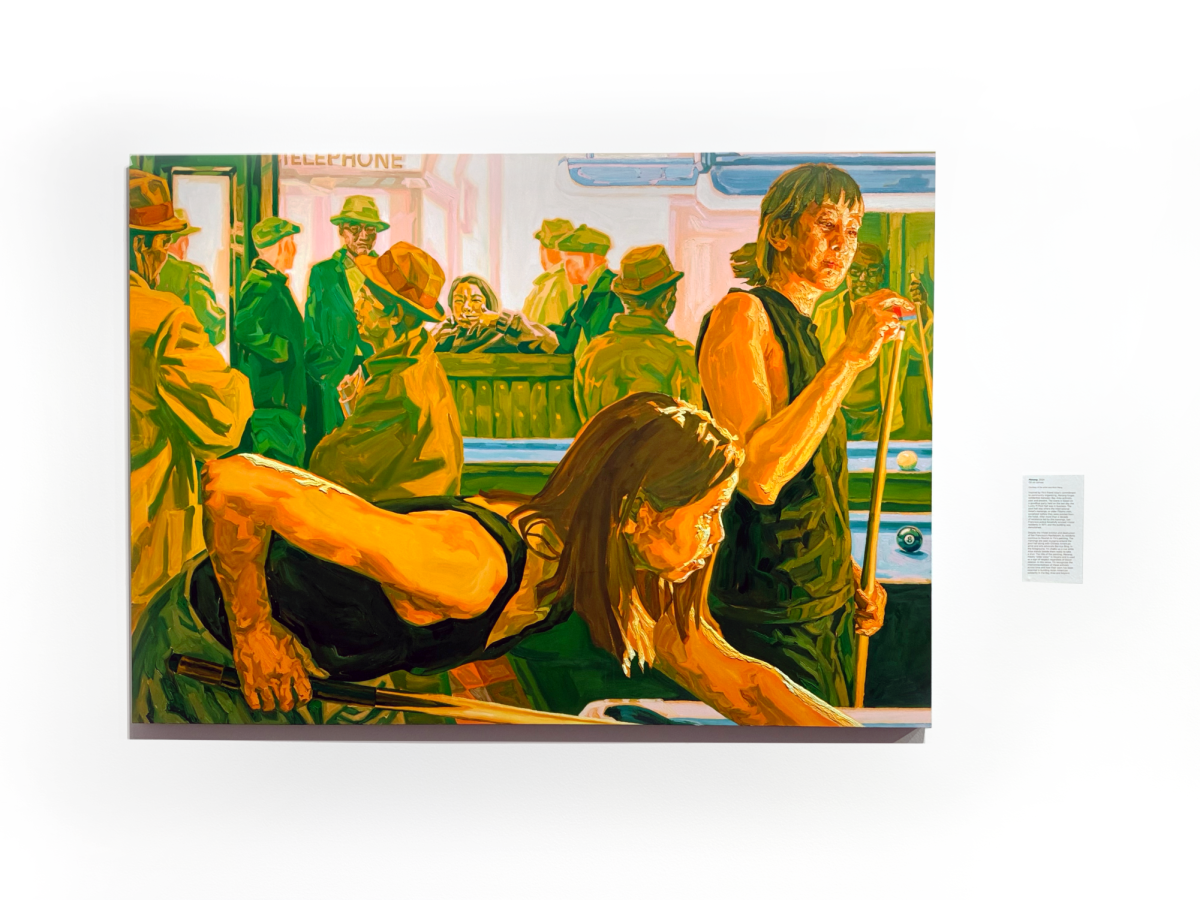

One of Yin’s personal favorite paintings is “Manang,” in her series “Kinship Across Time,” which features paintings of Yin’s “closest friends and the people in which [she] feels a sense of home.” In “Manang,” Yin and their friend are fictionally playing pool; in the background linger Filipino and Chinese men from a historical photograph of San Francisco’s Lucky M Pool Hall, a hub for the International Hotel tenants who led the 1970s landmark housing campaign to resist their eviction. Their friend in the painting introduced Yin to these oral histories; Yin incorporates these historical figures into the background of “Manang”, blending the past into the present.

“When my friend shares this history with me, it’s both an understanding of what we’re still living through now, and as well as our seeing resistance to displacement — for example, as an ongoing struggle and an ongoing legacy that people today are building on,” Yin said. “It’s a recognition of the precursors to displacement and of the grassroots activism that continues to evolve in San Francisco. I wanted to pay tribute to what she builds on through her community organizing in the Bay Area.”

This intersection of personal relationships and historical narratives underpins much of their work.

“I love hanging out with my friends, but to learn from the particular histories that give them meaning, and help understand who they are and where they’re going, is like another, deeper way of spending time with them,” Yin said. “For me, the soul of it is the process that comes visualizing the connections that a person is already carrying with them, in their day-to-day life.”

Through “Thirsty,” Yin reclaims narratives often overlooked in dominant historical accounts of the Chinese Exclusion Era, and focuses on the intersections between U.S. imperialism, capitalism, and Asian-American identity. “For the Chinese Exclusion Act, the ending of that act was not because anti-Chinese sentiment disappeared. It was because of the context of World War Two and how the US needed to strengthen relations with China against Japan,” Yin said.

For Yin, these histories are not static; they live within the relationships and structures that we have cultivated today, and continue to shape the present.

“The U.S. has its hands in so many parts of the world today,” Yin said. “The motivations for U.S. militarism, for example, are all very much connected to earlier histories of displacing people and exploiting laborers to amass wealth. So the reason why I look into this history is because of its presence in the contemporary. I don’t see history as closed books.”

In focusing on contemporary people, Yin discusses the implications of past events upon present structures and institutions.

“I focus on contemporary people because I very much believe in the possibilities that we each carry,” Yin said. “We are all very small in the scheme of history, but we also don’t know how our ripples are felt. I’m thinking about the subjects I paint who are living within different forms of oppressive constraints — and because of those constraints, they expand the work that has meaning to them, that is guided by compassion and ruptured histories, repairing that and making it intact.”

Yin draws knowledge and hope from their work — for Yin, it is both a reflection of the past and a hope for the future.

“They’re making something new,” Yin said. “They’re continuing what’s been fractured in the past. So I’m always looking at the growth — what’s living and growing — alongside what has been subdued or harmed in the past. I see it all as very interconnected.”

- What do you believe is the role of art in social change?

Jarod Lew: “I think it can be quite a collaborative effort, between social movements and groups of artists. They could be in the same conversation. There’s a lot of artists that are a part of those movements. I think about LaToya Ruby Frazier and her work that she did initially with her mother; she was a big advocate during the Flint water crisis. I think they go hand in hand sometimes, like that — Art and social justice can be tied together.”

Kathryn Rose Cua, Curatorial Assistant for the Asian American Art Initiative: “I think images have been used to build movements, to build community, to build power across many marginalized individuals throughout time. And I think that people intuitively understand that images hold power and meaning. I think that’s what’s really special is that looking at something is a whole different experience — it involves all senses. It’s something that is much more bodily.”

- Where do you believe the value of art lies, as opposed to a social media post or a wall of text?

Jarod Lew: “A social media post can sometimes be too literal and there’s no room for interpretation. So I think that’s why I enjoy going to a museum or going to a gallery. It’s what the art triggers in your own personal mind that could inspire or force you to think differently about how you view the world and your experiences in the world.”

Timothy Lai: “To me, art, text or social media are all different approaches to engage within a cultural discourse, they all inherently function differently and require their audiences to engage differently.”

Alex Darden, Cantor receptionist: “I think physically seeing it instead of reading about it gives you a whole new different perspective. You see all the colors, you see the textures, you have a spatial, physical relation to the piece, versus seeing it on a printed page and just reading it.”

Kathryn Rose Cua: “An artwork, in my opinion, creates its own meaning outside of whatever the creator’s intention was. You can say something and mean one thing and somebody could take it completely differently. It produces its own meaning that exists alongside the intended meaning. It doesn’t supplant it, but it’s also a truth. It’s also a reality.”

Livien Yin: “Something that draws me to art is its ability to create capacity in our heart in areas where perhaps we didn’t care about something before, but when we see it through another person’s lens or voice, it can enter into a realm of care within us and curiosity. I value art as a place that does not have to be didactic, because it may not give you solutions or clean readings over what it should offer. It’s a place that encourages, questioning, rethinking, critiquing what we’ve been given and what messages we’ve received in the past.

- Are you ever bothered by an incorrect interpretation of your work?

Jarod Lew: “I’m not ever bothered by a wrong interpretation, even if it’s a ‘bad’ one. If there’s some sort of feeling behind that interpretation — whether it’s a good or bad feeling — it ultimately does its job, right? It forces that person to think about what they’re saying, and I think that is the power of art. The interpretation, and the feelings that come out when you see something — that’s powerful and good.”

Timothy Lai: “No, it doesn’t bother me. I think I enjoy that my work has some relative open endedness that allows people to relate in their own way, even if that is different from what I intended.”

Livien Yin: “No, it doesn’t concern me. If somebody looks at my work and feels something entirely different than what I was feeling when I was making it, I would want there to be the space for them to have their own reaction to it. A work would be inert to me if it were to only have one reading. I think that openness is a part of the generosity of looking at art.”

- Do you feel pressure to make your art more “accessible”?

Jarod Lew: “I don’t try to make work that’s more ‘accessible.’ I think that I might strip away the importance of the work for me. I think accessibility is important for sure, but if I start to shift and make work that feels “more accessible” for other people, I think that might strip away the importance and even the authenticity of the work for me. So I try to keep making the work as I feel like it should be presented and made. And hopefully it resonates. And if it doesn’t, then maybe the next one will.”

Timothy Lai: “Yes. I think that is the nature of making art that attempts to engage with a larger public. If I made it solely for me, then I don’t have to concern myself with accessibility at all, right?

- How do you make work that’s personal to you but can resonate with others, still?

Timothy Lai: “When I was in grad school a professor once said, “the personal is universal,” and I think about that a lot. I think there are many aspects of our lives that are more relatable to each than we think. I am finding this more and more true. My experience is not separate from what happens in the world. So even if a work is based on personal experience, that experience stems from one’s participation within a society, culture and its events.”

Livien Yin: “I’ve found that when I look at other artists work — even if they’re sharing something that is very personal to their biography or to a specific cultural inheritance, gender, identity, and so on, even if it does not necessarily appear to be something that represents a wider swath of people, I’ve found that in that specificity and truthfulness to that artist’s experience that, it still leads me to reflect on my experiences, both in their differences from what I’m viewing, from what I don’t know, have not lived. That specificity can still bring people in. The work doesn’t have to reflect the audience to reach them.”

Aleesa Pitchamarn Alexander: “I think our [I’m referring to Asian Americans] experiences aren’t niche. My thinking is that the viewers of this show are also people like us. In that sense, if Asian Americans are my primary viewers, then the way that I approach the material is different than if I’m thinking about just a primarily white audience. This is an important thing that museum work can do because historically, we have only ever really centered the white experience or the white perspective and assumed that they are your primary viewer. I don’t make that assumption. I want to make something for us that I hope that everybody else can enjoy, also. But my primary motivation is talking to our larger communities.”

Museum Hours

Monday & Tuesday: CLOSED

Wednesday: 11:00 am – 6:00 pm

Thursday: 11:00 am – 8:00 pm

Friday: 11:00 am – 6:00 pm

Saturday: 10:00 am – 5:00 pm

Sunday: 10:00 am – 5:00 pm