What is womanhood? What does it mean to reclaim the female form? And what does it mean to see yourself through someone else’s eyes?

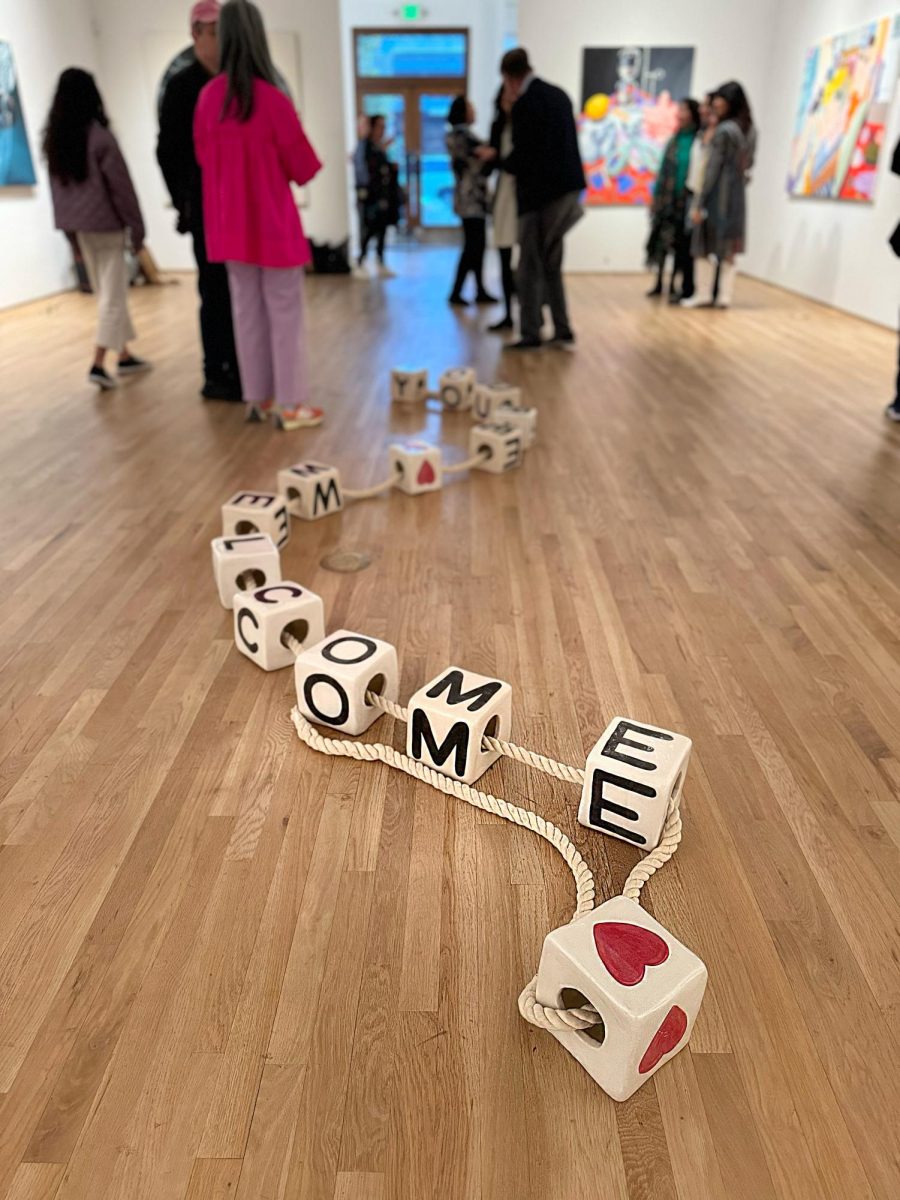

Seven female artists pose these questions at Qualia Contemporary Art’s new exhibition, “Our Bodies Through Our Eyes,” on view from Saturday, November 9, 2024 to Saturday, January 4, 2025 at Hamilton, Palo Alto. The exhibition comprises over 30 pieces that unearth layers of personal experience, feeling, and vulnerability, culminating in tender representations of the female form.

Director and exhibition curator Dacia Xu describes her inspiration for the show as a desire to “deconstruct the social ideas of femininity, beauty, and gender itself,” and to create a space for women’s representations of themselves to flourish organically, unconstrained by social compulsion or external repression.

“I want to create a show for women,” Xu said. “For how we look at our bodies. How we want to present ourselves. And to deconstruct the traditions and even the objectification of our bodies.”

The exhibition does precisely this: presenting work from multiple generations of female artists, who tackle these themes from distinct stylistic and cultural vantage points. Each artist dissects and reassembles the female body, examining how representations have changed across the past 50 years.

The artwork is personal and vulnerable. It doesn’t feel moralizing, in a time where feminist art is often typecast as shallow, radical, or reductive. Nor is the exhibition meant to be a sententious “lecture” on feminism or women’s political oppression. Rather, it’s a dedication to these seven artists’ personal, candid experiences of being women.

“The artists use their own angles to portray womanhood — it shows their authenticity, creativity, and you are immediately attracted to it,” Xu said. “They’re so different, but they all portray this idea: look at my body, but through my body, I want to show you my resistance to the traditional definition of femininity, this reclamation of the body, and also this healing.”

The artist Gina M. Contreras’ folk-inspired self-portraits particularly highlight this authenticity. Her nude portraits are deeply personal, tasteful, embracing nudity as a medium for introspection and agency. Her paintings distill the female form down to its plainest, rawest forms. The colors are flat, candid, deceptively simple, and, as Xu personally describes, “have this air of comfortability.”

“The most vulnerable a person can be is when they are nude,” Contreras said. “I’ve always been a bigger girl, so I’ve been told to cover up. In my paintings, I’m shedding that, exposing myself to a whole new audience. I feel it’s not vulgar. It’s very sensitive and appealing, and I’m very grateful that I do have an audience that can relate — that doesn’t only see the nudity but also the vulnerability.”

Her paintings are multidimensional, internally through the flattened, layered composition, and externally through the painting and audience. Contreras intended for her paintings to be almost conversational: you look at the paintings, the paintings look back at you. You look upon a window into her life, and she, in the painting, looks into yours.

“I love people, I love storytelling,” Contreras said. “I want people to build that connection with the art, with me, to be able to talk about why they’re connecting with a plus size Mexican woman, and understand what her feelings are, but also their own feelings too.”

The conversation is sincere, revealing. In that way, Contreras offsets these ideals of feminine beauty, counteracting them with her earnestness and vulnerability. In contrast, the artist Huang Hairong, satirizes these ideals, embraces them, and almost adopts them.

Huang presents an ironic, sardonic vision of femininity. Her photo-realistic paintings depict girls’ doll-like faces overlaid and fragmented by patterns of water, symbolizing the disturbance and fragmentation of female beauty. Their faces are so idealized that they become almost fetishistic — but this fetishistic quality is deliberate. She confronts our obsession with youth and glamorized beauty. And she’s forcing us to confront our own complicity in the commodification of beauty.

“She is exploring the commercial environment, and how women were — or even are, right now — portrayed and presented,” Xu said.

The water upon these girls’ faces is so pellucid that it appears almost like plastic, which Xu describes as an intentional artistic decision to “add another layer of interpretation.” It is almost like the packaging of women’s bodies — the physical, metaphorical objectification and commodification of beauty — into neat, sealed parcels.

We again encounter the intersection of femininity with consumerism through Annie Duncan’s sculptures and paintings. Her distorted still-lifes pair flowers and shells with modern beauty artifacts (razors, eyelash combs, and more) in everyday settings. Her paintings are figurative; she creates an uncanny, playful space, bridging the symbolic weight of these objects with their outsized presence in contemporary life.

“I started examining all these objects in my life that I realized were very feminine coded,” Duncan said. “Even something ‘dumb’ — a plastic razor or an insignificant throwaway object — embodies so many interesting cultural things. I’m reimagining historical symbols, and then putting them in a weird, surreal, modern context.”

Many of her works do this in intriguing ways. Her use of saturated colors and distorted forms subverts artistic precedent that, to Duncan, overemphasize identity politics that moralize the art.

“I don’t think I really leave with a message,” Duncan said. “Sometimes people react joyfully or sort of more introspectively, and I think that the bright colors and wonky forms are, in some ways, very friendly and inviting. Oftentimes that brings people in.”

Other pieces in the exhibition, like those by Stella Zhang, are more loosely “feminist.” At the back of the exhibition, her artwork is quieter, more introspective. Her pieces are abstract, philosophical, an esoteric contemplation on existence. In her work, Zhang emphasizes the internal conflicts contained inside the female body, rather than the physical, external part of herself.

All of her pieces pulse with remarkable emotion. Some of her art pieces contemplate the body “before your birth,” as frenetic energy waiting to be put to use; other pieces use crinkled sepia paper to limn the wrinkles of a woman’s wizened face. Nor does her art fit neatly into any one medium — it might be painting, mixed-media, or sculpting, it might be literal, or an abstraction. Perhaps she’s conveying some specific message, or maybe, trying to elicit some indescribable feeling.

One section of her works comprises small sculptures confined in the slots of a white shelf. These sculptures embody a sense of spiritual entrapment, each slot representing an enclosure for the human spirit. She evokes a sense of nervous, fragile energy and emotion inside someone, ready to come out. The various sculptures in the installation are an abstraction of this feeling, but the feeling is still grounded in the body, almost visceral.

Another section of Zhang’s works comprises mixed-media canvases that explore this idea further: this energy is powerful, but localized within the body.

“Afar, you look at nature and see that people are so small, so fragile — how they are struggling, or how they feel very peaceful for life,” Zhang said. “You feel your life experience from young to old, but you always change so much.”

There’s a constant theme of fragility and resilience in her art, which Zhang describes as deeply tied to memory and the passing of time. She coats her pieces in the yellowish-sepia color to imply the past, like an old photograph, almost.

“It’s very peaceful and contains a lot of memories,” Zhang said. “It touches my feeling. Everything is far away, but the color comes to life, beautiful like a palm.”

The color is quiet, plaintive, suggesting an intimacy that feels both deeply personal and universally human.

“Using everything I know, I am rethinking who I am,” Zhang said. “How can you find balance between weakness and struggle? What is a woman? What is your body? What is a human being? They always connect.”

This connection is binding, in “Our Bodies Through Our Eyes.” The show focuses on women, yet resists the tendency to frame their experiences as somehow separate from the broader human condition. All of these works of art, through their individuality and sincerity, claim the right to be considered just human. In that way, the contemplative joy that Zhang expresses speaks for all of these artists, each in their own way determined to claim a little more for women and carve out a space for their stories.

Museum Hours

Tuesday, Wednesday & Thursday: 11pm to 6pm

Friday & Saturday: 11pm to 7pm

Sunday & Monday By Appointment

How to get there

Location: 229 Hamilton Ave, Palo Alto, CA 94301

Alexander Nemerov | Dec 23, 2024 at 12:15 pm

A very thoughtful review. Particularly I see Stella Zhang’s works better having read Ellis Yang’s words.