ASI’s Journey to The California Science & Engineering Fair

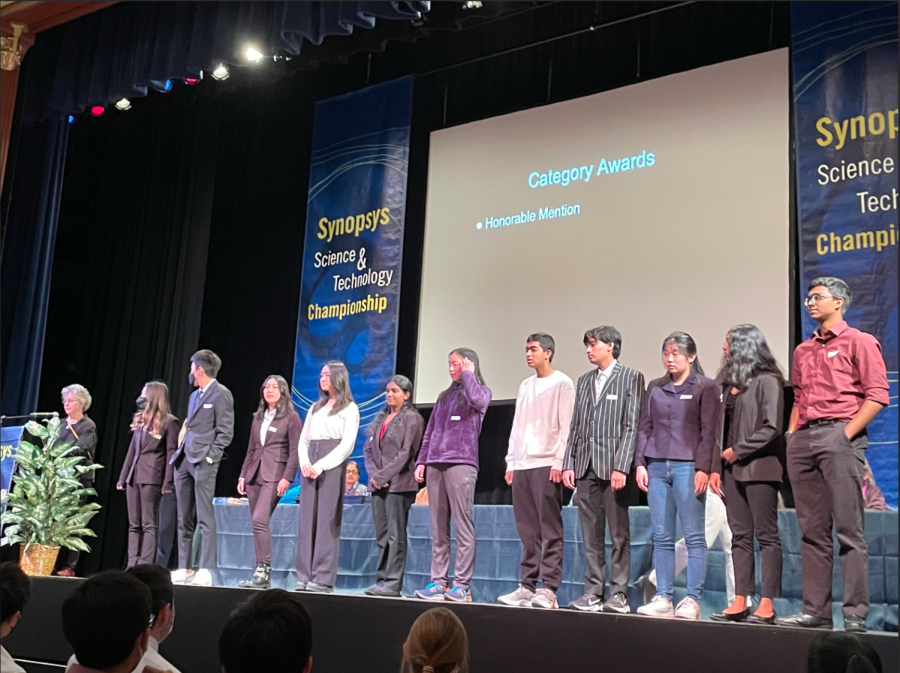

ASI members at the California Science & Engineering Fair.

The California Science & Engineering Fair is the final state-wide science fair of the school year for students in middle and high school. This year, five students from Los Altos High School’s Advanced Scientific Investigation (ASI) classes were given the opportunity to present their projects at the convention.

Sarah Su and Keira Chatwin

When coming up with ideas for their project, Sarah and Keira were inspired by the history of chronic diseases in each of their families.

“I had a lot of relatives with gastric cancer and other gastrointestinal diseases, and [Keira] has a lot of neurodegenerative diseases in [her] family,” Sarah said. “We were thinking about the [commonalities] of these two families of chronic diseases, and we wanted to find a common trend.”

That common trend was cellular senescence, the process in which cells grow old and age out of the cell cycle, which is the base of almost all chronic diseases. Reversing cellular senescence would pretty much cure all chronic diseases.

Sarah and Keira decided to tackle this with nuclear programming. Their initial hypothesis was to use an intermolecular Diels Alder reaction to construct the tricyclic core of forskolin. Or, in much simpler terms, they wanted to use a specific reaction that would create the center of a root extract of an Indian plant.

For Keira, science has been something she has always enjoyed, and chemistry in particular piqued her interest.

“What drew me to chemistry was that I could balance my love for science and discovery with this desire to do something that would make progress and benefit humanity,” Keira said. “I think I will always want to continue to support STEM efforts.”

Sarah started her STEM journey in her freshman year, when she started doing synthetic organic chemistry research at a lab nearby, and hopes to continue in the field as a physician.

“I’ve expanded my scope on the interdisciplinary nature of science as a whole, because I realized that there are so many factors that play into science,” Sarah said.

Both Keira and Sarah attribute their partnership as the reason they were able to stay motivated throughout their project. For them, working as a team makes the whole process more efficient and collaborative.

“They’re kind of like a dynamic duo,” ASI advisor Darren Dressen said. “They work really hard, there were a lot of times in class when they were having these little group meetings about their project.”

After spending a school year as ASI students, Sarah and Keira describe the class as a great resource and an entryway into the research world.

“I would definitely recommend ASI to any underclassmen,” Sarah said. “Mr. Dressen and Dr. Johnson do a really good job of introducing you to how to design your project, how to get into scientific literature, and a lot of the fundamentals [of scientific research] that people aren’t really familiar with.”

“It’s one of my favorite classes,” Keira said. “You are motivating your own discovery and I love that aspect of it, because it means that you get to work on what you are passionate about and you enjoy the process. It’s your choice, your innovation, your motivation.”

Sreyan Sarkar

Senior Sreyan Sarkar’s project deals with the plant valerian, which has been hypothesized that it can be used to treat anxiety and insomnia in various forms.

“The issue is that we don’t have any scientific research to back that hypothesis up,” Sreyan said. “So my project is basically taking the first steps to figure that out by figuring out the neurons and proteins in our brains that are used to actually interact with the compounds valerian has. And the way I do that is through these worms.”

The worms Sreyan is talking about are called C-elegans (Caenorhabditis elegans), a model organism used in a lot of research. They are a model organism because there’s a lot of analogies scientists can make from how the worms work to how our brains and proteins work. For Sreyan’s experiment, there are a couple of proteins that have the same function for the worms that those proteins have in our own brains. He is performing experiments to see how these proteins are responsible for interactions in the worms’ brains.

“Right now I’m just establishing which neurons and pathways we want to study the most, because other studies have established that valerian has some effect on anxiety and insomnia,” Sreyan said. “I’m trying to figure out exactly how it has that effect.”

He got interested in the project when his mentor at Stanford, Dr. Mariam Goodman, recommended to him that this was an area of open research if he was interested. It piqued his interest when he realized that valerian could be could have a large impact on drug development because some scientists are thinking valerian won’t have any of the usual negative side effects as other treatments for anxiety and depression, such as nausea and loss of appetite, but will have the same positive effects. Essentially, valerian could treat the same disorders without the downsides.

Sreyan experienced his main obstacle in the very beginning of his project: how to set it all up. The issue was that both to grow the worms and to perform the experiments, somewhat specific conditions are required. More importantly, the worms need to be in very sterile conditions. It took some time and problem-solving to establish the lab space and make it actually sterile and get the temperature and humidity levels right to run all of these experiments. But in the end, the hard work paid off.

“The thing I’m most proud of is just getting the results that I wanted,” Sreyan said. “Right now, I have results that show with a… pretty strong degree of confidence that this tax-4 protein I’m currently working with is involved and crucial for the pathways used to detect valerian. So I’ve greatly narrowed down which neurons I’m targeting, so that’s really nice.”

But he didn’t get there by himself: while Sreyan may be the only member of ASI going to CSEF without a partner, his work was done far from alone.

“I’d love to say I’m working by myself, but I’m really not,” Sreyan said. “As far as people in this class, I don’t have a partner, but [everyone in the class] sort of helps each other and we work together on things like finding papers for each other, sharing information. And from my brief experiences in the lab, that’s how actual research is too — it’s never really your own project is [just] your own project, everyone around you is always giving you little tidbits of information that’s helpful.”

Beyond his classmates, Sreyan has a mentor at Stanford who has been helping him out with finding a lot of papers and getting access to resources, as well as giving him the worm strains he has worked with; Johnson also provides him with support in-class.

“Sreyan is super independent, but he has been great about checking in with me and having me check his slides and things like that,” Johnson said. “I think mostly for him I’m providing moral support.”

Audrey Tsai and Bridget Liu

Juniors Audrey Tsai and Bridget Liu worked together to take a unique approach on Parkinson’s disease, a brain disorder which interferes with movement and coordination.

“In Parkinson’s disease, there’s a lipid metabolism imbalance, so there’s too many monounsaturated fatty acids,” Bridget said. “Basically what we’re doing is we are stopping the synthesis of these mono unsaturated fatty acids by synthesizing novel CD one inhibitors.”

But their project didn’t begin with their current niche approach to Parkinson’s. Bridget and Audrey decided to look into lipid metabolism after they had started with focusing their project on cell genetics. Their hypothesis was that their best working analog would be the one with the least sterical inhibitions.

“Our initial project proposal was that we were going to modify the cell genetics and see if that affects Parkinson’s,” Audrey said. “Then, we realized that genetics wasn’t really the best angle because there was this whole new angle on lipid metabolism that not a lot of people were looking into.”

Audrey and Bridget made their project work by playing to their strengths and developing ideas together.

“I’m better at chemistry and Audrey’s better at bio, so we kind of split it up that way,” Bridget said.

“I think what really helped was having a partnership,” said Audrey. “I don’t think science can be done alone. It’s really about having that person to constantly bounce ideas off of, look at things critically, and keep each other on track when we are really tempted to slack off. I think if I was working alone, I’d be a lot more complacent and be like, ‘Oh, this is good enough.’ Because I have a partner, we’re challenging each other.”