Art and Stem Funding

It is a widely accepted notion that there is a heavier focus on STEM classes and programs as opposed to art at Los Altos. But is that true? The Talon investigates the allocation of funds to the STEM and visual and performing art departments.

March 1, 2020

Introduction

In technology-dominated areas like Silicon Valley, many people value STEM-based careers over those in art. Consequently, it seems that more grants and public schools are increasing funding towards STEM-related programs over the arts. Los Altos appears to have become a microcosm for such a shift in society, though for more complicated reasons than the simple undervaluing of art—there are a variety of factors at school, district and state levels, causing a noticeable difference in the culture and resources of the two fields.

Funding Complications

According to principal Wynne Satterwhite, the MVLA School District allocates a total sum of money to the school based on enrollment, which she then distributes to individual departments. This distribution is based on departments’ previous budgets and is adjusted to meet further individual needs.

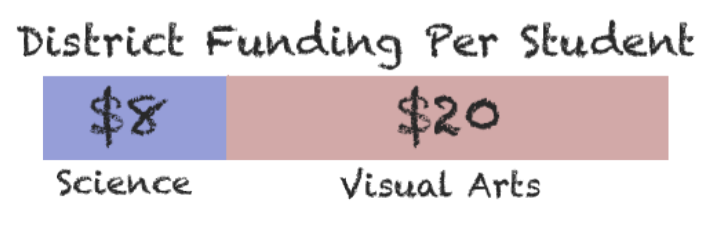

This 2019-2020 school year, the science department received $19,000 from the school, according to science department coordinator Darren Dressen. On the other hand, the school supplied the visual arts department with $3,055 for materials, according to art teacher Christine An.

Because there are 75 sections of science—which includes the traditional classes in biology, chemistry, environmental science, biotechnology, physics and forensics—this amounts to roughly $8 per student, assuming an average class size of 30. With only 18 sections of art, and far fewer students, their funding amounts to $20.36 per student.

The school provides the music program with around $6-8,000 per year using district funds according to instrumental music department coordinator Ted Ferrucci. He says Satterwhite is very generous in her willingness to find a way to get more money if the instrumental department needs it.

However, the school is not the only source of funding for these departments. They also receive money from grants, donations, or directly from the district. The amounts of these outside funds vary significantly, which may contribute to the overall impression that STEM classes are valued more than art at Los Altos. Dressen’s single section of Advanced Science and Investigations (ASI), for example, received $15,000 from the district.

This impression is further complicated by the fact that the Los Altos Academy of Engineering and Design receives funds entirely separate from the science department. AP Physics teacher Stephen Hine and math teacher Adam Anderson received $10,000 four years ago from the MVLA Foundations Innovative Learning Grant to buy starting equipment like 3D printers for specialized classes like Design and Prototyping and Robotics.

This program gained more traction when former associate superintendent Brigitte Saraff wrote a Career and Technical Education (CTE) Innovation Grant for the academy, which this year alone provided $100,000 to the program for materials, equipment and training. The grant provides funding for the first two years of each course the Academy develops, and the district is expected to pick up that tab after the grant expires.

But grants like these are not as easily available to the art department. Art teachers do not have the CTE credentials required to apply for a CTE grant. Even if they could be appropriately credentialed, they would need to substantially change their curriculum to qualify for an Innovation Grant. According to An, the department has not applied for grants designed for art because the requirements do not align with their current needs; they are either project-specific or pay for unneeded large equipment rather than standard art materials.

As a result, the visual and performing art departments rely on donations from students and families to meet additional needs.

The visual art department requests a $50 donation from each student in introductory art classes and a $100 donation from students in AP art classes. The total amount of student donations this 2019-2020 school year amounted to $11,130.

“Art supplies are so expensive, especially for photography, so we rely heavily on donations to purchase materials and we always have to be very careful with what we are spending,” art department coordinator Jessica Hayes said.

Similarly, the instrumental music department relies on a booster organization to raise roughly $50-60,000 per year to support band staff and all instrument repair and instrument purchases according to Ferrucci.

Art Department Frustrations

Though funding sources are more complicated than they seem, these differences in budget have created the impression that the school values the STEM departments over the art department.

“I feel that the art department is not a priority and is undervalued,” An said. “In order to have students produce high-quality work, we need the right amount of materials.”

Art students expressed similar sentiments.

“Even in AP Studio Art, I have to go out and get my own materials sometimes because we don’t have enough money,” senior Damla Aydin said. “It’s not like that for other classes because they already have all the materials.”

The art department also expressed concerns unrelated to funding. Teachers and students were upset by the cancellation of the latest art show. An said it had been scheduled months ahead of time but canceled a few days before the date because of a conflict with the Holiday Faire run by ASB.

“Student artworks should be displayed with respect because our students work hard every day to be professionally presented,” An said.

According to assistant principal Suzanne Woolfolk, the art show could not take place that day for purely logistical reasons. The custodial staff would have been overwhelmed if both events were occurring simultaneously in two locations. Administrators attempted to reschedule the show, but were unable to find a date that provided sufficient notice.

Furthermore, the limited classroom space and number of teachers in the visual arts department has required several sections of art (like Drawing 2 and Drawing 3) to combine into one class period with one teacher. Additionally, in the 2018-2019 school year, students in painting and drawing classes had three different long-term substitutes before a permanent teacher was hired.

This is not to say that the school is at fault for these particular circumstances; according to assistant principal Galen Rosenberg, it is both expensive and difficult to hire a new art teacher in this technology-focused area, and there is currently not enough space to have another art classroom.

Moreover, the high pressure and technology-dominated environment of Los Altos and Silicon Valley could be pulling focus towards a higher investment in STEM.

“Students are in a highly academic, high-pressure environment, and it’s pulling kids away from music at the level of commitment that we used to have or just playing in the ensemble that they want to be in,” Ferrucci said. “It used to be a no-brainer that Wind Ensemble kids were playing in Jazz Band, too. And now it’s like, ‘well, I need a free seventh period.’”

If you can’t beat ’em, join ’em

There is still room for more collaboration between the departments to thoroughly integrate art into STEM. Recently, the STEM department, specifically the new skills classes, have made efforts to collaborate with the art department, such as Design and Prototyping and National Art Honor Society working together to create props for Los Altos’s production of “High School Musical.”

“I definitely think that art could be supported more,” Hine said. “I’m hoping that we can help because we’re trying to partner with art and eventually create engineering art classes. These would be skills classes that teach students how to draw technical sketches, read blueprints or maybe use illustrator or computer modeling software to make a visual representation of something.”

At least in the Silicon Valley, reality might just dictate that art take this “if you can’t beat them, join them” approach. The ease with which STEM classes find grants and investments may come as a result of broader cultural trends in the Silicon Valley. As Hine said, “engineering and computer science are very sexy.”

Column: Visual Arts in the Valley

Most high schoolers pursuing art or design are commonly asked an age-old question: How are you going to make money? I’m no stranger to the precautionary tales of studying non-STEM subjects. But ask anyone who works at a top-five tech company: artists and designers are in demand. Silicon Valley’s traditional roles of creators and programmers are increasingly interdisciplinary, and high schools should match this shift by investing in creative programs for artists and non-artists alike.

In the past two decades, designers like former Apple Chief of Design Jony Ive have shown the tech world that creativity is a valuable and scarce resource that determines how a product will perform. Today, many successful startups like Airbnb are founded by artists and designers who can solve problems with an empathetic, human-centered design process. Companies like Facebook and Google are actively recruiting within the fields of product design, human-computer interaction, and user experience design to work at the intersection of creativity and technology. In the contemporary Silicon Valley workplace, designer-artists create beautiful and functional products in fields like AI while engineers implement functional systems with user-oriented design thinking. Even cities like New York are looking for designers to create green spaces in the fight against global warming.

Creative visual arts are critical to innovation in Silicon Valley because it brings aesthetics and humanity into technologies. Institutional leaders like Stanford’s Hasso Plattner Institute of Design see the value of creative thinking, so they have developed their design program to empower students of any major. In the admissions process, they’ve also allowed applicants of any major to submit a visual arts portfolio. Stanford has enabled researchers, scientists, and artists to use creative processes to make an impact in fields ranging from special education to environmental policy.

So what can our school do to empower its students?

We can start by enabling our amazing art teachers to teach creative thinking to more students at our school. Art teacher Christine An has worked with National Art Honors Society (NAHS) to bring interdisciplinary and conceptual art into our school. Working on her own time, she has invited Los Altos alumni who work as artists and designers to host workshops and guest seminars. Last year, Nvidia researcher Helen Broering hosted workshops introducing students to video production, while Intuit product designer Courtney Sandlin showed students her career in interaction/user experience design. These sessions open student eyes to creative careers, give them confidence in pursuing art, and show them the impact that creativity can make. But we need to do more than show possibilities—we need to let students explore ways to bring creativity into any discipline, and we can’t do that without expanding the art department to provide more guidance and resources for students.

Over the past four years, An has provided invaluable guidance in studying design and visual arts. Up until freshman year, I had always kept my computer science pursuits separate from visual arts, but she encouraged me to bring them together. Since then, I’ve worked on projects ranging from wearable special education learning tools to poetry-writing neural networks, blurring the line between artistic pursuit and computer engineering. But not all art students have a background in STEM, and not all STEM students have a background in art. Los Altos’s greatest flaw is that departments are segregated, where students have partitioned interests that often don’t come together.

We can move towards interdisciplinary visual arts for all students by increasing the art department’s budget, which currently relies on parent donations to maintain supplies. We can also consider additional visual arts curriculum, and a studio supplied with spaces and resources required to innovate with fabrication and technology. As we lay down foundations for new buildings, now is the perfect time to fulfill a demand for creativity from tech companies and educational institutions alike. Maybe the answer to a truly innovative curriculum lies in the arts.

Column: Arts—Not just an Easy A

In fifth grade, I had just started at a new school. Searching for an outlet to make friends and express my creative side, I joined choir. Despite having absolutely no choir experience, it soon felt like a community to me.

Choir not only felt like my second home, but it also taught me invaluable skills, not just in music, but in teamwork, that I carry with me to this day. When I graduated, I was so emotional about leaving behind such an open coterie. However, I had hope that I could find something similar within Los Altos’s choir program.

Yet, within the first week, I could already tell it wouldn’t be the same. Even though I had choral experience, I was automatically placed in the beginner girls’ choir because I was a freshman, so I was singing songs I’d sung before. The class was more relaxing than challenging, and although it was nice to sing without pressure, I missed the sense of urgency that came from preparing for concerts. It felt like the sole purpose of our concerts was grading, not putting on a quality performance for people to watch.

I felt disappointed that many of my peers saw the class as an easy way to fulfill graduation requirements. Excluding some, most people in my choir were in it for the arts credit and an easy A. I could sense my teacher’s passion about music, but my previous experience and the choral program overall felt overlooked compared to other electives.

Honestly, I doubt this would happen in the STEM program at Los Altos, because STEM courses are generally viewed as difficult classes focused upon career preparation. Even the introductory STEM courses are challenging, and no one would take them expecting to just glide through and get an A. Also, introductory classes are not always necessary to take higher level classes in the STEM department. AP Computer Science, for example, can be taken without Intro to Computer Science.

Overall, this shows that the art departments are often seen as a crutch for students desperate to obtain credits through an easy class, sometimes at the expense of the people serious about the class, which you rarely see in STEM.

Instead, people should appreciate the arts for what they can contribute to one’s education. While STEM teaches quantifiable skills, the arts teach immeasurable qualifiable skills like creativity and composure, and that shouldn’t be discounted. The arts teach transferable skills that can be applied to a range of careers, while elective STEM courses often teach skills so specific that they force you down a certain career path.

It’s great that schools have started to recognize the value of the arts by putting the A into STEAM, through STEAM Foundations classes and STEAM Week. But it doesn’t feel like the student body has caught up. You can’t just add a letter to an acronym—you have to show you’re giving it equal attention. Sometimes it feels like there isn’t even a point in making it STEAM instead of STEM.

Instead of district-wide change in funding of the arts department, we should first work on changing the culture around the arts. Arts classes should not just be promoted as a way to relax and slack off, but as a way to explore your creative side and discover alternative career options.

One way we could do this is through an arts introductory class similar to the STEAM Foundations class, focusing on an introduction to painting, drawing, photography, acting and choir. This would be an option for people without arts experience, giving them a way to fulfill their arts credit and try a variety of arts within one class.

Additionally, the arts department can offer placement classes for higher level arts classes, so people aren’t required to take a class they are overqualified for and can instead learn to their level.

It’s time to show the arts the love they deserve. They’re the foundation of education, which many of us forget.