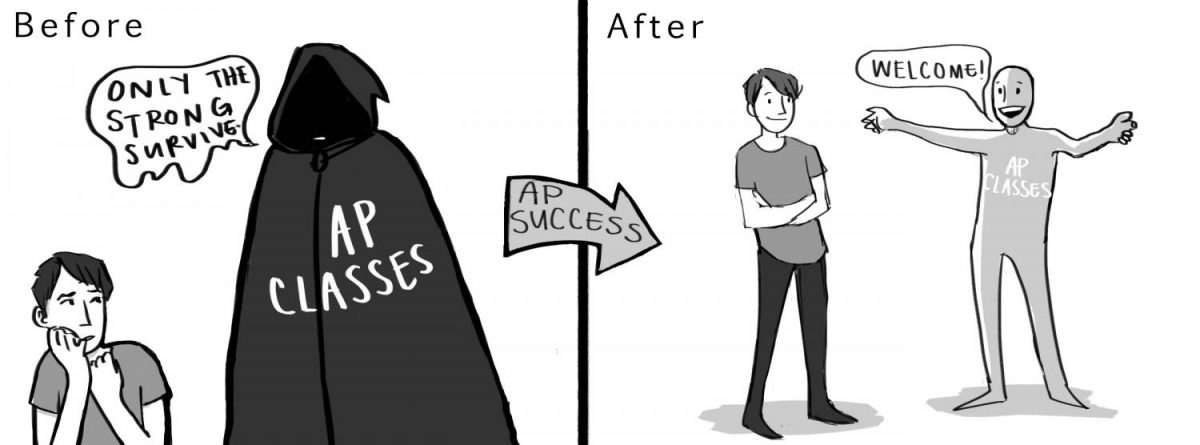

AP Success Aims for Accessibility

September 28, 2017

To improve the classroom experience for underrepresented students in AP classes, Los Altos teachers teamed up with Stanford researchers in a program called AP Success. The program aims to create strategies for teachers to develop an environment in which students feel comfortable approaching material.

Closing the achievement gap in AP courses has long been one of Los Altos’ goals. While there have been attempts to address AP inequity among students of different backgrounds such as first-generation students and females pursuing STEM, AP Success uniquely emphasizes school-wide discussion by bringing teachers together to share their ideas for improvements.

“This is the first time since I’ve been here that we’ve actually tried to address the issue of AP access at the school level,” AP Microeconomics teacher Derek Miyahara said. “We’ve been doing things, but until now, the efforts have been more departmental and course-level.”

All AP teachers are required to be part of the program and attend monthly meetings to discuss how to make AP classes more inclusive to typically underrepresented groups because lack of accessibility can negatively impact individual student performance and drop rates in many AP courses.

“It’s a lot easier to get someone into a class [than] to get someone to stay,” AP Language teacher Keren Dawson-Bowman said. “Our ultimate goal is to get kids in, staying through and passing the class, and then the long range is higher scores on the exams.”

AP Success does not prescribe certain action for teachers to take to improve their learning environments. Instead, they encourage teachers to be reflective about their classes and choose what to do based on what their individual classes need.

“These changes come not because AP Success said, ‘You will do three icebreakers in your first week,’” Miyahara said. “Teachers would develop an awareness, like, ‘Oh, this class isn’t as talkative as some of my other classes, maybe we need to do another icebreaker.’”

On a teacher-to-student level, inclusivity efforts can include providing clear expectations for the course, encouraging communication among students or teaching notetaking strategies — anything that helps students feel comfortable and prepared.

“I definitely can’t speak for other teachers, but what I try to do is [be] all about happiness and energy,” AP Physics teacher Stephen Hine said. “I’m always very excited to start the year and talk about physics, and I try to bring humor in as much as possible and create this atmosphere.”

In addition to discussions among teachers, the AP Success program includes the voices of students they hope to help. A panel of AVID students attended a meeting with members of AP Success to talk about their experiences in AP classes and what they felt teachers should change.

“When [the AVID panel] left, we looked at the homework that we assign and we tried to be reflective about it,” AP Calculus teacher Laraine Ignacio said. “We want it to be valuable for everyone, whether that’s sharing best practices, asking people what resources they’d need or sharing a resource that helped students.”

Los Altos’ AP Success program is the product of one of the school’s “innovation teams,” groups of teachers that work on potential reforms for the school. One team, which focuses on underrepresented students, contacted Stanford researchers who had recently secured funding to create programs to further educational equity last year. The Stanford team is working with three different schools that represent a range of economic situations.

“They wanted three schools where their problems were hugely different from one another,” Dawson-Bowman said. “We could learn from one another. I also think it makes for interesting research when you have a much more diverse group of needs.”

Last year, groups of representatives from each school met multiple times at Stanford to share their ideas and potentially apply them to their own schools. One such program implemented at another school is the Summer Bridge program, where students learn about the basic concepts required for their upcoming AP courses before school starts. Hine expressed interest in pursuing this program.

“In physics, we could have a whole week where we could go through symbolic algebra, because that’s technically not part of the curriculum but something students see in our course,” Hine said. “So if you spend that kind of time before school with students that might need extra help, that could potentially change a lot.”

Beyond such programs, future efforts to improve AP equity may depend on how successful current strategies are in terms of decreasing drop rates and improving AP test scores. One possibility is to focus on pathways to AP classes, which would help students in courses that feed into AP classes transition into more rigorous coursework.

Another possibility is to add AP courses that are identified by the College Board as relatively less rigorous. AP Human Geography, which Los Altos started offering to sophomores last year, was one of these courses.

“There are a few that the College Board is trying to play up as, ‘If your school is looking for something a little on the tame side for AP, this is a good intro,’” Hine said.

Teachers are continually thinking about accessibility and will continue to develop ways to help their students. Dawson-Bowman acknowledges that changes will not necessarily come quickly, but is excited about the program’s possibilities.

“I want students to realize how much their teachers care,” Dawson-Bowman said. “We may seem a little cold-hearted with how much homework we give you, but your success really matters to us. Even if a class is hard or really challenging, if your teacher is trying their best, that really helps.”